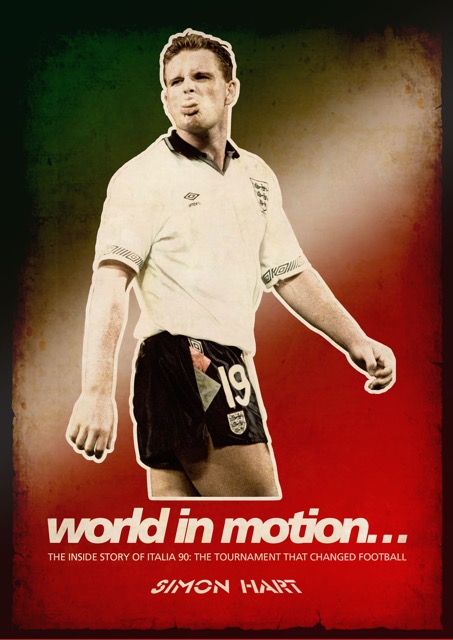

THE story of England at Italia 90 cannot be told without considering happenings off the field, writes SIMON HART in a chapter from his new book, World in Motion: The Inside Story of Italia 90.

Only five years had passed since the Heysel Stadium disaster, when a surge by rioting Liverpool fans contributed to the deaths of 39 Juventus supporters, killed as a wall collapsed in the antiquated venue before the European Cup final.

Five years before that, fighting between England followers and Italian spectators pockmarked the national side’s 1980 European Championship match against Belgium in Turin; the tear gas used by police spread to the pitch and led to a pause in play.

English teams had endured a ban from Europe’s club competitions in the five years since Heysel and now, on the eve of the World Cup, UEFA said it was ready to re-open the door but deferred a final decision until after the tournament.

After all, it was only two years since English fans had run amok in Düsseldorf during the 1988 European Championship, bringing 381 arrests and the withdrawal of an earlier FA application for the readmission of English clubs to Europe. In September 1989, 100 England fans were arrested and deported from Sweden after the World Cup qualifying match in Stockholm. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had urged the FA to “consider very carefully” withdrawing England from the finals.

Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, general manager of the 1990 World Cup organising committee, remembers ‘three or four meetings’ with Colin Moynihan, the British government’s minister for sport. “He was very worried,” he tells me.

“My rule was to first of all give assurances that we were able to control the situation very well and also to present to him a very clear project.” Namely, to put England on an island closer to Corsica than to the Italian mainland. “There was a very good reason: for safety [security]. Because you can’t arrive on Sardinia unless you’re the best swimmer in history, or by plane or by boat, so it was very easy to control everybody from the airport and from the port.”

Once the England fans reached Sardinia, its population newly boosted by 7,000 law enforcement officers, the daily hooligan-watch dispatches began.

On 6 June, the Gazzetta dello Sport led its Group F coverage with news of the expulsion of Paul Scarrott, a notorious football thug – or “the king of the hooligans”, as the paper labelled him. The reports of arrests and anti-social behaviour kept coming: 14 detained after a confrontation with police in downtown Cagliari three nights before England’s opening fixture; another three arrested for stealing bed sheets and trashing a room in their boarding house.

Fortunately, this drip, drip of unhappy headlines was only part of the story surrounding England’s supporters, for Italy proved the setting for a groundbreaking initiative by the Football Supporters’ Association (as the Football Supporters’ Federation was then called) to improve the lot of travelling fans.

Thanks to the efforts of FSA volunteers, Italia ’90 became the first World Cup with a fans’ embassy.

Today, when tens of thousands of football lovers descend on major tournaments – an estimated 500,000 supporters from across the UK attended Euro 2016 – information points for travelling fans are ubiquitous.

In June 1990, the landscape was very different. Huge numbers had yet to start following England. This was only the national team’s second World Cup on European soil since the 1950s, and the on-field failings and off -field fighting at the 1988 European Championship did little to entice fresh followers.

It was also five years before the advent of budget airlines (2.69 million passengers passed through Luton International Airport, as it was then, in 1990 compared with 15.8million in 2017).

Hence, it was possible to roll into Cagliari and pick up a ticket for England v Netherlands, the highest-profile Group F fixture, from a tout for half the face value.

Steve Beauchampé, one of the two main embassy organisers, recalls, ‘One of the things we offered people was advice on how to get tickets. England’s following was not massive. It was about 6,000 for the Ireland and Dutch games, and less for Egypt. It got a little bit bigger on the mainland, but even for the semi-final, it was probably only about nine or 10,000.

“There were sociologists out there – John Williams, Rogan Taylor, Adrian Goldberg who was working for the Sir Norman Chester centre. You had the journalists, too. I remember thinking, “How many people are actually here to cause trouble, and how many are here to monitor it?” The whole way the tournament was framed in the build-up to it in England and Italy was around hooliganism. Some journalists didn’t understand the distinction between a

hooligan and an ordinary fan.”

Beauchampé had been active in the early days of fanzines – he helped establish On The Ball, a Birmingham-based publication – and became involved in the nascent supporter movement that gathered strength with the founding of the FSA in 1985. Its voice became increasingly audible in the wake of the Hillsborough disaster, as Beauchampé notes: “Hillsborough made a massive difference to the way the football authorities regarded the FSA. A number of people, most of all Rogan Taylor, handled that impeccably, and we, as an organisation, albeit for the worst of reasons, received a major lift.”

As Italia ’90 approached, John Tummin, an FSA colleague, proposed a satellite office in Sardinia and came up with the phrase ‘football embassy’. The task of realising the plan fell to Beauchampé and Craig Brewin, leader of the London branch. It was Brewin, then working as a finance officer for a London borough, who put up the money.

“We got a grant from the Football Trust but didn’t know that was coming through until about the week the tournament started,” he explains. “So, I said to Steve, ‘I’ll underwrite it and pay all the bills for the first few weeks.’ It was about £5,000.”

They hired a suite of rooms on the first floor of the offices of Ansa, the Italian news agency, in Cagliari. Beauchampé adds, “The office was a base, but we spent time outside, handing out guides wherever we found people. Obviously, this was pre-mobile phone and internet, and then word of mouth gets around that there’s this place for England fans. We’d be out till midnight and later, just handing stuff out and seeing the nightly toing and froing between fans and police and Italians.”

For the England fan on Sardinia, there were bumpy experiences. Supporters entering the stadium for the opening game against Ireland, for instance, had all their coins confiscated. Later that night, a group of England fans found themselves in a confrontation with a gang of Italians outside the railway station after they were unable to return to their out-of-town camp sites, owing to a scarcity of buses. “It was a couple of miles’ walk back into town from the stadium, and a lot of people would have to find somewhere to bed down around the station, the bus station or the port, or stay up all night,” Beauchampé says.

One night Craig Brewin had one of his car windows smashed while driving a pair of English fans away from a trouble spot. Yet, he plays down the severity of the skirmishes that would be reported enthusiastically by the press. ‘There were a few stand-offs in the town late at night, but there’d be 50 or 60 people at most, and there were probably 5,000 England fans there.”

Brewin believes the mood music from the British government – negative messages from Moynihan, Margaret Thatcher’s sports minister, who had made a successful appeal for an alcohol ban on match days – did not help matters at a time when positive action was being taken, such as the FA’s founding earlier in 1990 of the official England supporters’ club.

“We were thinking most people were going there for a holiday, but he seemed to be talking as if everyone was going there to cause trouble, and you cannot possibly know that, particularly if the people with tickets had all been vetted by the FA as well,” he says.

Another member of the FSA team in Cagliari was Kate Quill, who was helping out as a volunteer interpreter, and she takes a similarly sympathetic view.

“For many it was their first trip abroad,” she says. “Many fans had simply bought a flight and made no preparation at all. They were unbelievably naive. In Sardinia, the younger fans were clearly overwhelmed during the first few days – the heat, the foreign language, the different currency, the stunningly

beautiful, and very sophisticated and self-composed, local girls. Just the general beauty and elegance of Italy was unsettling to them, I think. They stuck out like sore thumbs, but as we bumped into them again in different cities as the tournament progressed, it was clear some of them were enjoying Italy.

“I often felt that one of the biggest barriers to mutual understanding came down to very simple things. Italian culture is essentially a visual one, and they place a huge amount of importance on outer respectability. They take enormous pride in their appearance, and public displays of drunkenness or undignified behaviour are deeply frowned upon, across all classes and all income groups.

“So here they were, confronted by men stripped to the waist, sometimes quite overweight, bearing tattoos – which weren’t fashionable as now – sunburned chests, and smelling pretty bad because they were sleeping in campsites, or in the railway station, or on someone’s floor for the night. Add in a few beers before midday, and it’s really not a good look in Italy.”

Before the first match in Group F, leading Sardinian newspaper L’unione Sarda wrote an editorial in response to an attack on three England fans by locals, in which it said, “Maybe it was inevitable after people have talked about nothing else but violence for months, but the island has been taken over by hooligan psychosis with a result that every male English citizen between 15 and 60 becomes indelibly stamped as the hooligan.”

It was the second fixture, England’s meeting with the Netherlands on 16 June, which many had foreseen as potentially explosive. The previous autumn, an Ajax-Austria Vienna UEFA Cup tie was marred by visiting goalkeeper Franz Wolfhart being struck by an iron bar – an incident leading to a one-year UEFA ban for the Amsterdam club – while the next month, two Feyenoord hooligans threw nail bombs into an Ajax section during a league game.

Violence did erupt on 16 June, but there was no involvement from the travelling Dutch fans, already then kitted out in those now trademark bright orange

costumes. The trouble originated, rather, with an England supporters’ march to the stadium.

The FSA had warned people not to take part. One of the leaders of the march, Beauchampé remembers, was “this guy who was involved in the London branch of the FSA and was a bit dodgy. The police came to see us and said no to this march. When we told him it’d get out of hand, he used this phrase which is engrained in my mind: ‘If the police put up barriers, the lads will smash right through them.'”

The most dramatic account of what came next is found in Bill Buford’s book Among The Thugs. He writes, “With the world’s media bearing down on

them, the supporters wanted to take on an island militia that had been preparing for this event for months. The lads wanted to fight the police.”

Buford’s book relays a sequence of events which begins with a policeman firing a handgun into the air and ends with fans charging down a hill towards an Esso station, where a plate glass window is shattered. It was here that the Italian police responded and John Tummin, an embassy volunteer monitoring the march, was assaulted by Antonio Patea, the assistant police deputy.

“Patea was a nasty piece of work,” Beauchampé asserts. “The very first time we met him, all he could see was England fans as hooligans. John went up and spoke to him about the way the police were batoning fans, and he hit John across the face.”

If powerless that evening, the FSA embassy did deliver many positives according to Brewin. One example was a raffle of England equipment to raise funds for research into sickle cell anaemia, a disease unusually common on Sardinia.

Brewin explains, “We organised football matches with the locals which the England travel club still do regularly now. We’d try to arrange a meeting with local fans wherever we went. I remember driving around Naples and trying to find the leader of the Napoli ultras, just to talk to him and share experiences.”

Brewin’s only previous England away game had come when the magazine When Saturday Comes had organised a coach trip to Albania for a World Cup qualifier in March 1989 to allow right-minded England fans the chance to watch the national team – only to end up engaged in a confrontation with a separate coachload who were making Nazi salutes.

He expounds, “I wanted to do it because I wanted to put on a show for the people back home – to show how England fans can behave and how they should behave and to try to send out a message to other people who’d want to follow England: that, actually, a lot of people who go and watch England raise money for charity and are mixing with the local community.

“I wanted to present to the world a different view of the England football fan, whereas Steve [Beauchampé] wanted to do something for football fans that

needed doing because no one else was going to do it. We both had a different view of why we were doing it, and I think we probably achieved both. Steve and I did another one in Sweden in ’92. In ’94, we didn’t go and in ’96, it was in England, so there was a long period where they weren’t doing them. It started again in ’98 when I wasn’t involved. Everyone does them now. Maybe we were ahead of our time.”

This is an extract from World in Motion: The Inside Story of Italia 90 by Simon Hart, which has been published by DeCoubertin Books and is available here: www.decoubertin.co.uk/

Recent Posts:

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: David Rawcliffe-Propaganda Photo