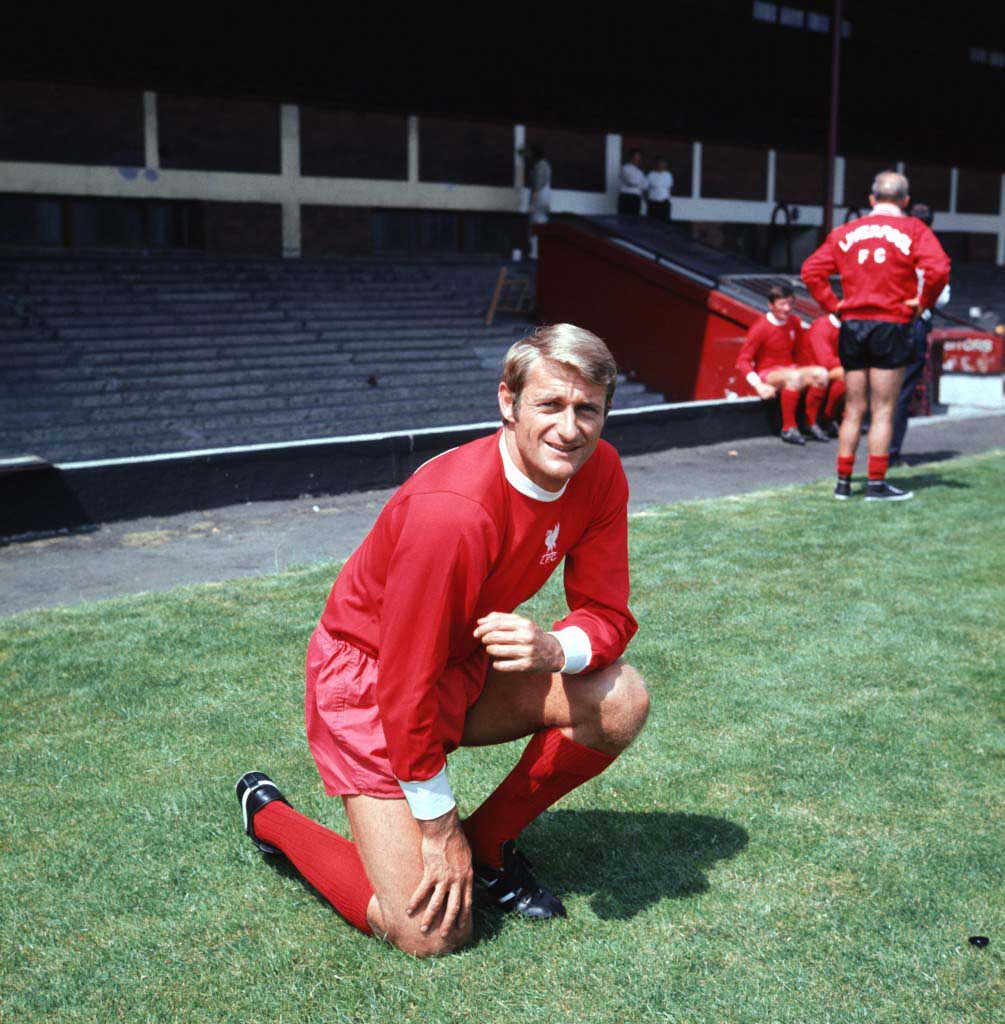

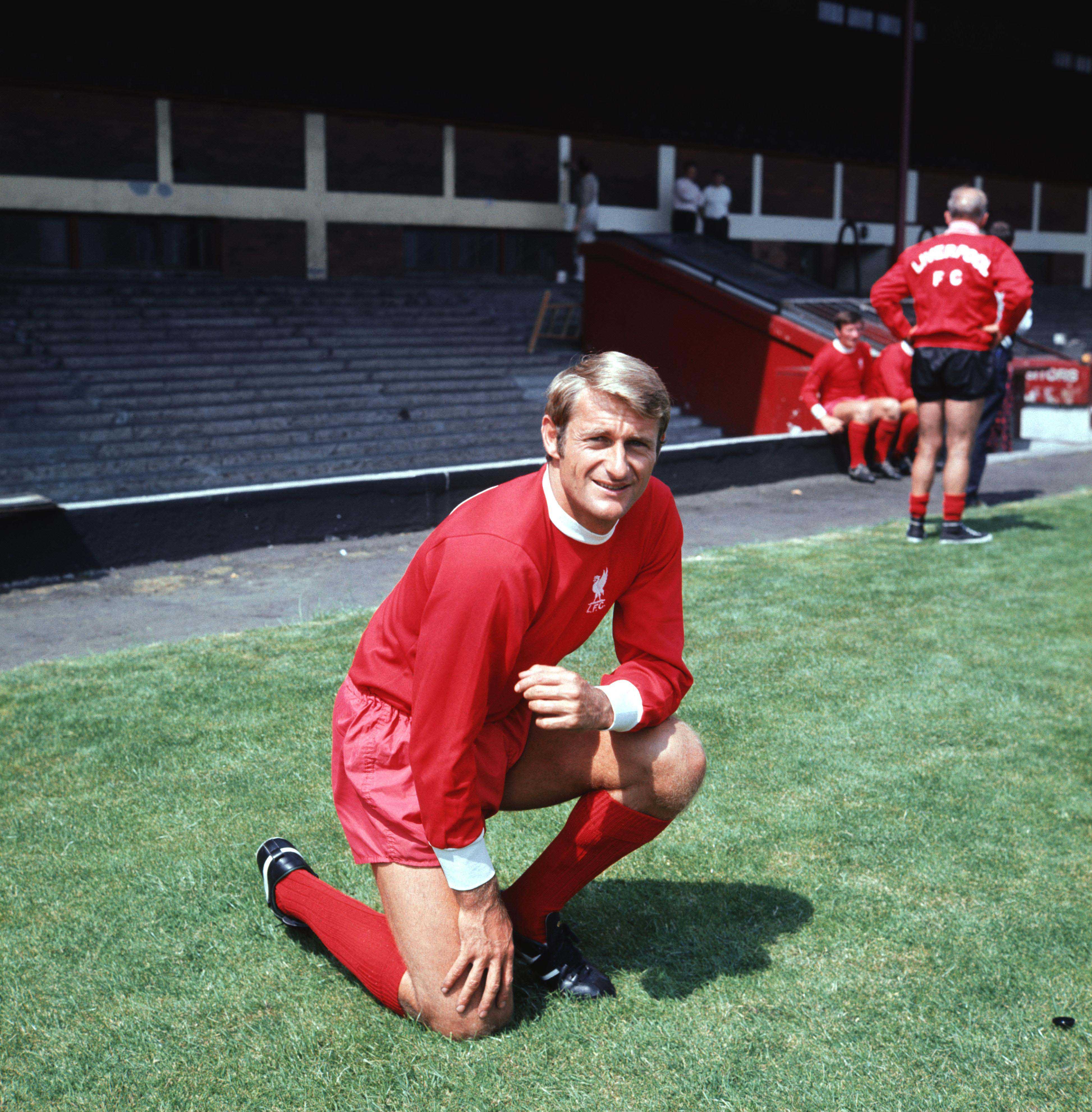

THE term ‘legend’ is one bandied around all too readily in the modern game but Roger Hunt, who is 77 today, is a player truly worthy of the mantle. Sir Roger, as he was affectionately christened by The Kop, still has a burning passion for football.

THE term ‘legend’ is one bandied around all too readily in the modern game but Roger Hunt, who is 77 today, is a player truly worthy of the mantle. Sir Roger, as he was affectionately christened by The Kop, still has a burning passion for football.

When we meet in a Merseyside hotel, Hunt is soon into his stride, recalling the glory years and discussing the game today. “I’m football daft,” he says. “Just like I was back then.”

Hunt’s astonishing goal haul of 245 league goals remains an Anfield record, while he played a key role in Liverpool’s first FA Cup win in 1965 and England’s solitary World Cup win in 1966. Hunt, playing under Bill Shankly, also helped Liverpool to promotion from the Second Division in 1962 when he struck a record 41 goals in 41 games.

He also fired 31 and 30 league goals in the Championship seasons of 1963-64 and 1965-66.

In the modern game, where players are routinely discarded at 16, 17 and 18, Hunt — a latecomer to football at the highest level — says the opportunity to don the red shirt would probably have passed him by. And he even admits there was a stroke of luck behind the big break that saw him go on to make history at Liverpool.

“I’d always wanted to be a footballer for as long as I can remember and I used to practice and practice and practice,” says Hunt.

“I played whenever I could but I was never picked up. I signed for Bury when I was 17 when they were in the Second Division. I went for trials after I’d written to every club in the area. They were the only ones who answered.

“I must have done okay because they signed me on amateur forms. But I was working in the family haulage business then and it was training two nights a week then the match on Saturday and I couldn’t do it — it was too much.

“I asked if they would sign me full-time and they were not sure about me. I had a trial for a month and was paid as a professional but there were about 46 players there, a massive staff. I only played twice in the four weeks and I was a reserve for the other two.

“They couldn’t make their minds up and I decided to go back to the family business. I thought I had missed my chance then.”

Hunt continued to play football though, playing up front for Stockton Heath Albion (now Northern Premier League Division One side Warrington Town). He later joined the army and played for Devizes Town while on national service in Wiltshire, returning to play for Stockton Heath one weekend in three while on leave.

It was at Stockton Heath that Hunt was spotted, aged 20, by Liverpool scout Bill Jones, himself a former Anfield player and grandfather of former Liverpool right back, Rob Jones.

“It was a stroke of luck that he was there at that game,” says Hunt.

“Bill approached the manager, Frank Worrall (an FA Cup winner with Portsmouth in 1939) and said Liverpool wanted me on trial.

“So I was playing for the ‘A’ and ‘B’ sides when I was home on leave. I’d scored a few goals and just before I was demobbed from the army, Liverpool played me in the Central League (reserves) team.

Fulham goalkeeper Tony Macedo dives at the feet of Liverpool’s Roger Hunt

“All the players were pros — they were dropping a pro to play me — and I remember walking into the dressing room and one said to another, ‘I wouldn’t stand for that, being left out for an amateur!’. It was really competitive and we played Preston in a big important match. If we beat them you were paid a bonus.

“I scored the first goal but the pace of the game was too much for me — I wasn’t as fit as them. I was playing football but not to this intensity. Joe Fagan was the manager and I remember he came over to me at half-time and said, ‘I want more from you’. I was struggling to breathe!”

Hunt was warned to improve his fitness and on the way back from Anfield that day he again had doubts as to whether he would make the grade as a professional.

“My dad was driving me home,” said Hunt. “And he said to me, ‘I think you should forget any ideas about being a professional footballer and come back into the family business’. I thought that’s good, really encouraging!

“But with Joe saying that I trained and ran and did everything. All through my career I had that at the back of my mind — you’ve got to work, work, work. If you really want it you’ve only got so many years to get it. And I was a bit late.”

Hunt need not have worried. After coming out of the army, he played five games for the reserves, scoring seven goals. And that was enough to convince then manager Phil Taylor to give him a chance in the first team.

“It was fantastic,” says Hunt. “I had taken the place of Billy Liddell, a hero, but he was coming to the end of his career. We played Scunthorpe and I wouldn’t say the game passed me by but it was much quicker than the Central League, which was a good standard.

“There were 32,000 people there that night and I’d never played in front of more than 5,000. But I scored and once you do that you feel like you’re 10 foot tall — you can do anything then, it’s a big weight off your shoulders.

“That was a midweek game and on the Saturday we played Middlesbrough. Phil Taylor told me to have a rest and played Billy and they got beat 2-1. After that it was Scunthorpe then Derby, two games on the trot. We drew at Scunthorpe and we beat Derby 2-1 and I scored the winner.

“After that I was never out of the team for 10 years, I never got dropped. There were no substitutes until the latter end of my career, after the World Cup in 1966.”

Shankly replaced Taylor as manager and kept faith with Hunt amid a clear out of players on his arrival at Anfield in December 1959.

“He made a big impression straight away,” recalls Hunt. “There were 40-odd players at Anfield and he got us all in the dressing room, introduced himself and said there’s going to be a lot of changes here. He said to us: ‘We’re going to win things, we’re going to get promotion and if anybody isn’t going to try or isn’t interested, you’re out’. He got rid of a lot of people.”

Hunt — like everyone who played for the great man — clearly has the upmost respect for Shankly and singled out his enthusiasm as the key attribute to his success. But he also emphasised that Shankly was an expert in motivating players, as well as being tactically astute.

“He could transform you,” says Hunt. “He never put you down — you were always better than the opposition. He gave you a lot of confidence. He would take you to one side and give you little tips but he also changed the whole training schedule. He made training like a match situation.

“We used to do a lot of running, 20 laps, and not much with the ball. With Shankly we did loads of stuff with the ball. There were a lot of 3-a-sides and we did a lot of intensive stuff, under pressure. Shankly was very tactical but Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan and Reuben Bennett had a lot of tactical nous, too. They put a lot of ideas in.”

Everyone who came into contact with Shanks has a story to tell, and Hunt is no different. “There are so many,” he says, before pausing to think.

“I remember we were playing Manchester City at home. Me and Tommy Lawrence lived in the same area. He was going to the game with his family and I was going with mine. There was a massive traffic jam on the East Lancs Road and we both tried different ways to get to Anfield.

“We both got to near the ground for about ten to three. When we got there Bob Paisley started giving us loads of stick but Shanks came in and said, ‘No Bob. Take your time, get yourself ready, there’s no problem’. And off he went to tell the officials the kick off was delayed! I think the club was fined about 300 quid for that, which was a lot of money in those days. But Shanks just kept his calm.”

In 1961 Shankly signed Ian St John from Motherwell for £37,500. The Saint formed a lethal partnership with Hunt who says the pairing clicked from the first time they played together.

“Ian came in as a centre forward and I was inside right,” said Hunt. “As soon as we played together we had an understanding – we thought the same way. We could exchange positions and he would come deep and I would go up front but mainly he was the centre forward. He was great in the air and had this great knack of knowing where to go and seeing where the opportunities where.

“We had a telepathic thing going on — I knew what he was going to do and vice versa. We played together for nearly 10 years and it was great to play with him — he was very unselfish.”

Hunt and St John combined to great effect for one of the biggest moments in Liverpool’s history — the club’s first FA Cup win in 1965.

The extra-time goal that put Liverpool ahead against Leeds in front of a 100,000-strong crowd at Wembley came from Hunt’s head — a stooping effort from Gerry Byrne’s cross.

Billy Bremner pulled it back for the Yorkshiremen before St John headed home Ian Callaghan’s cross to win it for the Reds and put the famous piece of silverware in the Anfield trophy cabinet for the first time in Liverpool’s 72-year existence.

Roger rates his opener as the favourite of his goals for Liverpool, second only to a volley past Gordon Banks which sunk bogey side Leicester on the road to Wembley that season and sealed a semi-final spot.

“The FA Cup was very, very big then,” said Hunt. “It has been devalued now and big clubs don’t treat it the same. It was on a par with winning the league in those days and Liverpool had taken a lot of stick for having never won it.

“Winning the FA Cup, getting promotion from the Second Division and winning the championship in 1964, the first since 1947, were the highlights for me at Liverpool .

“To be involved, play in the final and winning it for the first time — you just never forget that. The reception when we came back to Liverpool was absolutely brilliant — there were about a quarter of a million people there and they were even on the roof of Lime Street Station!”

Hunt ended the 1966 season a league champion (again) and played a big part in England winning the Jules Rimet Trophy in the summer. While he’s best remembered as the player who swore Geoff Hurst’s goal crossed the line in the final (and still does), Hunt scored three goals in the group stages on the way to the historic win.

“The World Cup has to be the highlight of my career,” said Hunt. “I felt the FA Cup was equally as big at the time but as the years have gone on, and we haven’t won it again, it’s made it different.”

A legacy of being the closest player to THAT goal is Hunt is asked over and over again if the ball crossed the line. “It always comes up when there’s a controversial goal-line incident,” he said.

“People still say to me now ‘Why didn’t you just put it in?’ because I was only four yards away. As Geoff Hurst hit it, I anticipated it, Wolfgang Weber was marking me but I got in front of him — I was there , ready if it didn’t go in.

“So it hits the underside of the bar and came down, I turned away because I thought it was over the line and would be bouncing into the roof of the net. But it went in, came back out — I was still convinced — and by then I couldn’t get it because it came out at an angle and Weber headed it away.

“I am sure it was over but I’m not sure the linesman could see it. But I loved scoring goals and I was scoring goals all the time. I’m not going to turn away if there was a chance of a goal — it was instinctive. I can’t say I would do anything different if I could do it again.”

2009: Roger Hunt and Ian St John join the parade of Liverpool legends on the pitch at Anfield to commemorate 50 years since the appointment of Bill Shankly

Hunt’s halo slipped just once in his Liverpool career, in March 1969. The gentleman of football had fans at Anfield rubbing their eyes in disbelief when he took off his shirt and angrily threw it in the direction of the dug-out after being substituted in a cup replay against Leicester.

“I suppose you’ve heard about this,” said Hunt, rolling his eyes. “That was the beginning of the end.

“The substitute rule hadn’t been in that long and at Liverpool it had never been discussed that it would be used tactically rather than just when someone was injured. So I was looking around going ‘who, who, who is it?’ Anyway it was me!

“We had a bit of a row about it and it was just before Shanks started to change things. He decided he was going to bring other players in as even though we had done well we had not actually won anything for three years.”

Hunt dislocated his collar bone which put an end to his contribution in the 1968-69 season but he started the following campaign as first choice until one day he was told by Bob Paisley that he was wanted in the boss’s office.

“I think I had played 11 games and scored six goals. I thought he was calling me in to tell me I was doing alright. He said, ’Middlesbrough have made a bid for you’. I was in complete shock.

“I knew then that was the beginning of the end. I said ‘no, not interested’ but I did eventually leave for Bolton. It was my decision, he said you don’t have to go, but I knew I wouldn’t be playing much.”

Hunt ‘s last goal for Liverpool came against Vitoria Setubal in a European Fairs Cup match at Anfield in November 1969. He joined Bolton shortly after, aged 31.

Three years later, he stepped on to the Anfield turf for one final farewell at a well-deserved testimonial. The gates were locked hours before kick-off as fans clamoured to pay their respects. An astonishing gate of 56,000 was recorded, with many thousands more reported to be locked outside.

Hunt had the chance to move into management but after taking his preliminary coaching badge, he decided it wasn’t for him.

“I didn’t think I had the temperament to be a manager or a coach,” said Hunt. “You’ve got to keep a lot of people happy as a manager and I had the opportunity to go into the family business so I opted for that. I’ve never regretted it. I played football for another 20 years in friendly games, charity games, ex-international games.”

Hunt’s contribution to football was belatedly recognised by the Queen in 2000 when he was awarded an MBE. It was nothing new to us though. To Liverpool fans, he’d always been Sir Roger.

– First published in Well Red magazine

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: PA Images

My boyhood hero and still is. A great Liverpool player and so under rated. Of all the England players who won the World Cup, he was the only one not to be included in the variety of ‘Best Team’ selections by various ‘experts’. Still, he is and always will be Sir Roger Hunt!

Yes but how many interceptions per game did he make? And what about successful take ons – were they higher or lower than Jimmy Greaves? Is his pressing rate 0.7 pressowatts per game or higher????

FFS, these are the things that matter.

Ooohh, you have destroyed his reputation in one thoughtful sentence.

How far did he run? Did he track back? These are all absolutely essential stats in analysing players. Who cares that we adored him and he made us proud? A shipload of goals is irrelevant – how many shirts would he sell??!

Roger please get in touch. This is from an ex Devizes Town reserve player, I was a year younger than you.

Do you remember playing Walthamstow Avenue in the Amateur Cup. For us it was the biggest highlight in the clubs history.

I remember watching the 65 cup final against Leeds with my dear wife it was in the iron gate pub in edgeware road a message from you would really please us both thanks Roger