THE thing about memories is that they are always there for you, writes NEIL SCOTT. They sit patiently somewhere round the back of your cerebral cortex until summoned into action on a moment’s whim, to provide a rose-tinted window to a time long gone.

Like many compulsive nostalgists, a great number of my fondest memories are football-related. Years are defined by Cup Finals, summers by World Cups. To me, the word ‘panini’ will always evoke the youthful excitement of tearing open a pack of pristine football stickers, and the inevitable deflation on finding yet another Paul Mariner, rather than being some fancy shorthand for a squashed Italian sarnie.

It is, however, easy to romanticise childhood memories. Generally speaking, a wide-eyed 14 year old is more easily impressed than a jaded 40-something and, with passage of time often serving as an aid to embellishment, it is only wise to approach an old man’s reminiscences with a certain amount of caution. That said, and with a clear mind and an unshakeable conviction, I urge you to cast aside your scepticism, to charge your glasses, be upstanding, and raise a toast to the purveyors of the most beautiful football this weary cynic has been fortunate enough to witness.

In most cases, a football team’s greatness is affirmed by its successes. It is rare for a team to ultimately fail yet still be widely regarded as the best of its generation. Notable exceptions include Hungary in the 1950s and Holland in the 1970s – sides which captured the imagination of the world despite falling at the final hurdle.

That the Brazil team of 1982 failed is undeniable, but never has failure looked quite so magnificent. Were it not for them, the World Cup in Spain would have been remembered chiefly for Gerry Armstrong’s bustle, Claudio Gentile’s savagery and Kevin Keegan’s inability to find an empty net from six yards out. We owe them our deepest thanks.

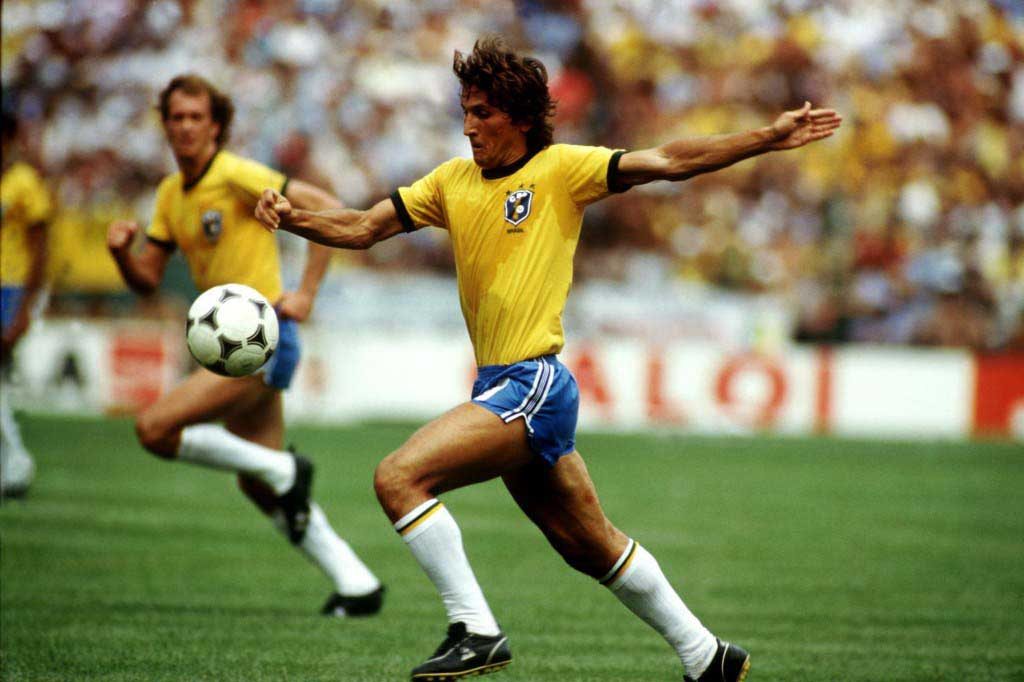

The names have been ingrained on my consciousness for nearly 30 years now. Valdir Peres. Junior. Leandro. Oscar. Luizinho. Cerezo. Falcao. Zico (above). Socrates. Eder. Serginho. If I close my eyes I’m instantly back there, rushing home from school to take up my place, transfixed, in front of the telly, a Texan Bar in one hand, a Rubik’s Cube in the other (it was the ‘80s, it’s what we did – ask Peter Kay).

With a freedom of expression seldom seen either before or since, this Brazil team produced football that spoke of endless opportunity and breathtaking spectacle. Their endless fluidity and failure to follow conventionally prescribed tactical formations would reduce modern day analysts to blubbering wrecks. This truly was, in the prescient words of Alan Partridge, ‘liquid football.’

A nominal 4-2-3-1 set-up would typically convert to something that loosely resembled a 2-1-5-2 approach, but in reality even this fails to do justice to the positional flexibility of Tele Santana’s team. Orchestrated by the irrepressible genius of Zico, ably abetted by the chain-smoking, expansively bearded, toweringly elegant Socrates, Brazil’s attacking philosophy was crystal clear. In basic terms it was the ultimate manifestation of several age-old clichés: “Let the ball do the work.” “No matter how many the opposition score, we’ll score more.” “Attack is the best form of defence.”

Whereas Barcelona have specialised in intricate short-passing patterns, content to bide their time to prise out an opening, Brazil opted for 30-yard one-twos, overwhelming opponents by the sheer variety of their play and the range of options that they fashioned at will. One-touch, two-touch, pass and move and move some more, flicks and tricks.

They could exploit the width offered by perpetually overlapping full-backs, Junior & Leandro, the direct (in every sense) precursors of Roberto Carlos and Cafu. They could drive through the middle, with Zico dropping deep undetected to take possession before crafting passes of such precision it was as if they has been designed using nanotechnology.

In truth, they could do whatever they pleased. There was no obvious game-plan, no agenda, no secret formula. There was a ball and a million different ways to get it into the net.

All of which is not to say that this was a team without weakness. Perhaps inevitably, any concept of defence seemed an afterthought, as if it was an unsightly blemish on the overall aesthetic. Whether this reflected naivety or arrogance, ultimately it was to be their undoing.

They fielded a goalkeeper who bore all the physical hallmarks of a disillusioned accountant and performed like a man who felt that goalkeeping was something that disillusioned accountants really shouldn’t get involved in.

And centre forward Serginho was the only Brazilian in history to be able to control a ball further than most players could kick it. Stepping in at late notice to replace the injured (and more obviously talented) Careca, Serginho was in the mould of a classic English number 9. Big, strong, good in the air and as subtle as a housebrick to the back of the head. It was, in some ways, akin to adorning Michelangelo’s David with a pair of plastic comedy breasts and a jester’s hat.

Their path through the World Cup was littered with moments to treasure. I implore those who remain unconvinced to watch the YouTube video above. Start with the two late goals in the opening match against Russia, after the hapless Peres had casually ushered a speculative long-range effort into his own goal, as if he felt his teammates needed a bit more of a challenge.

The response was unequivocal. First Socrates exploded a shot of such force into the roof of the net it could have conceivably demolished a tower block, while Eder, with a flourish that seemed to suggest this was a team intent on cementing its legacy, teed up a rolling ball and unleashed a swerving, dipping volley that left Russian keeper Dasaev, considered by many the world’s best, rooted to the spot like a rusty oil-rig.

In the next match, against a Scotland team that could boast the likes of Souness, Dalglish, Wark, Strachan and Hansen, Brazil gave a masterclass of relaxed, inventive attacking football. After again falling behind to an early Narey effort, they simply stepped up to a gear that was beyond anything most teams could envisage. Zico curled a free kick into the top corner that could not have been more precise had its trajectory been plotted by NASA, a triumph of technique and unerring accuracy. But even this was upstaged by a sublime angled chip from Eder (right) that left hapless Scottish keeper Alan Rough wondering whether repeated World Cup humiliation was some kind of karmic retribution for once sporting the worst footballer’s perm since Bob Latchford.

Zico again took centre stage against Argentina, poking home from close range after an Eder free kick, which changed direction more than a latter day Radiohead album, crashed against the crossbar. He followed this up with an exquisite, defence garrotting pass to the rampaging Junior, which didn’t so much ask to be converted as vehemently insisted. There seemed no limit to what this team could accomplish. We were entering uncharted territory here and, for a generation of English teenagers raised on a decade of international failure, it felt like the romance and the wonder of World Cup football was finally, thrillingly, revealed. We were all Brazilians now.

At which point it all came crashing down.

Brazil went into the final second-stage group match against Italy needing only a draw to progress to the semi-final. There was nothing to suggest that it would be anything other than a routine exercise. Italy were in many ways the antithesis of Brazil – cautious, disciplined, occasionally brutal – and appeared over-reliant on a 40 year old goalkeeper (Zoff), a defender prone to acts of dubious legality (Gentile) and a misfiring striker recently returned from a two year match-fixing ban (Rossi). The outcome, surely, was a formality.

Well, not quite. This was the day Brazil’s defensive failings were finally, fatally exposed. In a match still remembered as one of the finest in World Cup history, they fell behind on three occasions to an Italian team suddenly perfecting the art of the counter-attack. The previously anonymous Rossi struck a hat-trick, in a devastating display of predatory finishing; in response Brazil threw caution to the wind, unable or unwilling to abandon their free-flowing philosophy. It was an enthralling, compulsive spectacle, which, in hindsight, was as much a fight for the soul of the game as it was a struggle for a place in the last four.

With 20 minutes to go, a sumptuous Falcao strike brought the scores level at 2-2, which was enough to send Brazil through. A time surely for restraint, for prioritising the bigger picture at the expense of immediate glory? For most teams, yes. But the Brazil of 1982 were anything but most teams. And they weren’t about to forego their principles if it meant settling for a draw.

So they kept on attacking. And, inevitably, it cost them the World Cup. An unmarked Rossi grabbed his third goal; Zoff denied logic in keeping out a last minute Oscar header; and Brazil, shockingly, were beaten. In the words of Zico, it was “the day football died.”

The result left a scar on Brazil’s footballing psyche. It wasn’t just a team that had been defeated in the Spanish sun, it was an ethos. Their failure may be seen as the point at which pragmatic, results-driven, safety-first football became the default, with flair and expression increasingly sacrificed at the expense of discipline and tactical rigidity. To this day few teams have successfully replicated the Brazilian template, the elusive ‘jogo bonito,’ although certain elements may be detected in the Liverpool of 1988, Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan and Barcelona.

As for Brazil, they have captured the World Cup twice since the trauma of 1982, each time with teams that were largely lacking the fantasy of Zico and his colleagues. Were these victories any less sweet for being achieved through the harnessing of individual ability within an organised, practical outlook? I doubt it.

But don’t expect me to think of them the way I think of the team that shone so brightly back in 1982. When Zico and Socrates and Eder and Junior showed that football could be magic. And when teenage kicks were played out in yellow and blue. They’re my memories and they’ll always be with me.

Pics: Press Association

Really enjoyed that. I was 10 in the summer of 1982 and was absolutely captivated by that Brazil side. I’d never seen anything like it before and I fell in love with football, rather than just specifically Liverpool. Unfortunately, few sides have come close for sheer enjoyment to that Brazil side since. Serginho was the Brazilian Brett Angel. If Careca had been fit, Brazil would have won that world cup.

I was so glad my own team Belgium made it to that Worldcup and won the opening game against World Champion of 1978 Argentina, but I cried during weeks after Brasil was out of that Worldcup. I hoped they would take revenge in 1986, but that team was only a shadow of the team of 1982. How the best team doesn’t win !!!

Nice article. My first true World Cup (’78 is a bit of a blur). I have never seen a team like Brazil ’82. They were phenomenal. No team has ever come close to producing such beautiful football, apart from Barca 2009-11, and I know who’d I rather watch. Stephen is correct in that if Careca had been fit, that trophy would have been Brazil’s (well, that and no square balls across the box…). Serginho was an appalling striker, we likened him more to Mark Falco.