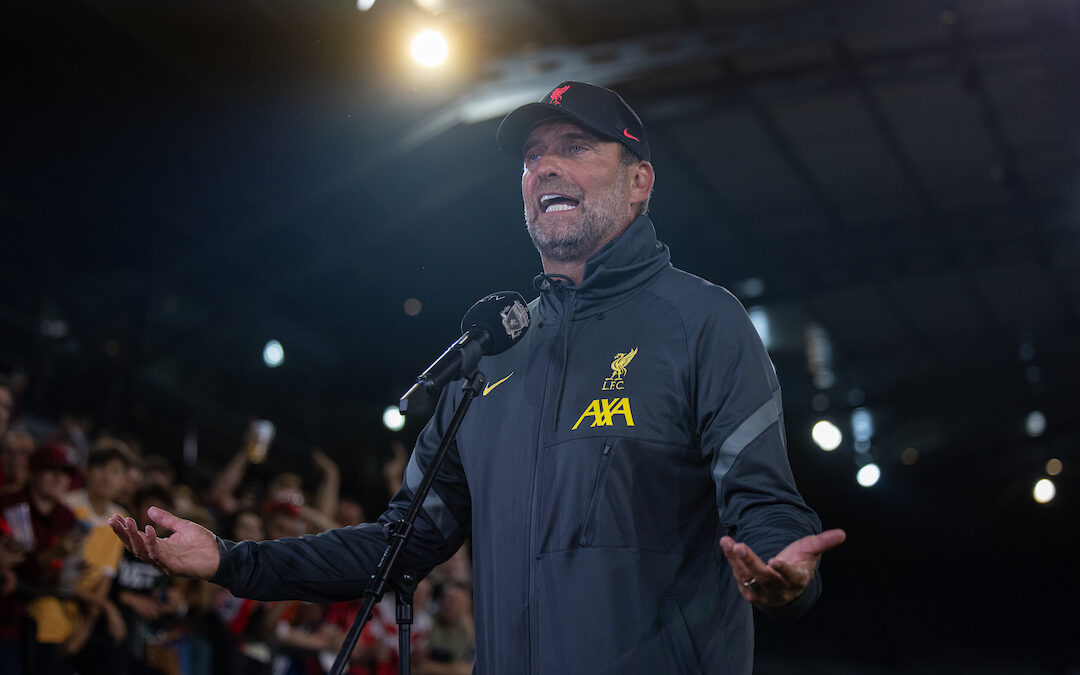

Alastair Campbell once insisted that Jürgen Klopp should consider going into politics, but there are a few reasons the German won’t do so…

BACK in spring, when off we went gathering cup finals in May and the unprecedented no longer seemed unthinkable, former Labour spin master Alastair Campbell posted an open letter to Jürgen Klopp in The New European, for where he now writes as editor-at-large…

“Dear Mr. Klopp,” he began. “You’re wasted in football… Thought about going into politics?”

Campbell, a lifelong Burnley fan and friend of the since departed Sean Dyche, was actually doing his homework. I mean, really doing his homework. He happened to be taking a German language course at the time and, for an assignment, had been asked to write someone a letter. Presumably a German someone.

Evidently, he’d been caught up in all the excitement; the kind that, every once in a while, breaks its borders and sweeps beyond the parochial and beyond even the game.

The quadruple was on, and history was in the offing. Pep Guardiola was blown off course, sufficiently piqued by the media’s perceived red bias to forget he was closing in on the title himself. Liverpool were the only show in town.

Campbell wasn’t alone. Writing for The New Statesman in late May, by which time the league, at least, looked less likely, Michael Henderson – long-time arts critic and cricket correspondent for any number of broadsheets – was still in a bit of a swoon.

Paraphrasing the painter Thomas Gainsborough, he proclaimed that: “We are bound for heaven, and Jürgen Klopp is of the company.” While Henderson was getting lyrical, Campbell stayed on point.

Such are Klopp’s leadership qualities that it’s no surprise he attracts attention from outside of his chosen field. Providence has caught up with Klopp, however, and six short months later those traits are undergoing a stress test as he works to reverse a relative downturn in fortunes and challenges that multiply by the game.

The strain had been evident, as referee Anthony Taylor could attest after sending Klopp to the stands against City. Not an episode Klopp will look back on with pride if he looks back at all.

But something had to give. He was about to find some freedom again, more than just the Freedom of the City. He seemed stuck in a moment, half a yard short like his team, visibly tired though admirably reluctant to use that as an excuse, and short on ready answers.

As for the seven-year itch, too many have been too quick to see it and many too slow to point out the differences and call it for what it is – nothing but coincidence. On punditry’s periphery, where Gabby Agbonlahor and Didi Hamann turn hot air into money, the unthinkable is never unsayable. If Klopp’s time isn’t up – yet – then for some it’s at least up for debate.

It’s a broad church, as with any club, and maybe a few have started to wonder what we’d do without him. We’re closer to the end than the beginning – that much is true, unfortunately – maybe it’s more fruitful to wonder what he’d do without us?

Campbell would be the first to admit that Westminster is no place for someone who knows exactly where he’s at his most influential. It’s an entertaining thought experiment, one that the Labour Party tried twice to make a reality in the 1970s with Brian Clough, according to legend, but one that’s grounded in a very real malaise.

In the UK, we’re nearing the end of a calamitous political cycle, caused in no small part by an ongoing failure of leadership. Don’t bet on any visionaries rising to meet the permacrisis any time soon.

And yet you’ll find leaders in sport. In the fight against racism, professional athletes have woken up to their capacity to speak out in a way that elected officials have not.

In the six years since Colin Kaepernick first sat out the US national anthem before taking the knee, kicking off the most visually effective protest in sport since Vincent Matthews and Wayne Collett’s Black Power salute at the 1972 Munich Olympics, football has at least found a collective voice on the matter – or, at least, players and fans have.

As a global business it’s still locked in an eternal tango with the forces of capital. The World Cup in Qatar, studded with stadia from an alternate reality and built on the suffering and death of migrant workers, seems like a brazen rebuke to the very notion of rights – a calculated fuck you to anyone naïve enough to dispute a state’s assertion that it can do and buy whatever it wants.

Klopp has excused players from the burden of protest in Qatar, highlighting their exclusion from the decision-making process that brought the tournament there in the first place, and insisting that the onus lies with politicians and journalists. It’s common sense to point out that if we were ever serious about doing anything about it, then 12 years ago was the time.

But it’s also astute, and indicative of an innate political sense and an adroit approach to topics that often embarrass coaches and players alike. His surefooted handling of the FA Cup final spat, which stoked Boris Johnson-fanned outrage in the right-wing press, showed a willingness to wade in when necessary.

He was careful to acknowledge the problem, but showed savvy in speaking to his own constituency while asking a simple question. If people weren’t standing, he reasoned, then surely, they wouldn’t do so without reason? Better, perhaps, for the great and the good to seek out that reason, rather than simply point the finger?

It was a telling moment, not least because it illustrated just how Klopp differs from the average Prime Minister – and they are average – and just why his gifts would wither and die in the political arena.

Johnson went straight to the Westminster playbook when he jabbed the finger, probably garnering a few votes on the way. Klopp asked a question and had us all wondering why politicians won’t ask those questions themselves. For Johnson it was all about expediency and personal ambition. Klopp displayed an inherent selflessness born of faith and honed in service to the clubs and fanbases he has dedicated himself to.

It’s that essential modesty – the promise of the Normal One, if you like – that sets him apart from politicians as we know them. He knows the difference between winning and beating his opponent – a graceful distinction – and while there may be politicians we could say that of, there are none I could readily name.

His selflessness infers a deep trust in others, players, and fans alike. In his own words, ‘everyone is responsible for everything’. Keir Starmer might just get there in the end, but I suspect it will be a while before anyone in the House of Commons voices anything quite so grown up.

Klopp isn’t at the mercy of the voter, though he’s as vulnerable to results as any manager in the end. Perhaps his free hand is a luxury some MPs can only dream of. But sport has filled the space vacated by politics long ago and he finds himself exactly where he should be, at a club that has provided an apt arena for his communitarian instincts.

Those tempted to view his side’s current travails as symptomatic of a failure in leadership might do well to see his resolve as an exemplar of true leadership.

There’s always been something a bit un-football about Klopp, something bracingly untypical. You sense a hinterland, populated by friends as likely to be surgeons or filmmakers as football coaches.

When the time comes, voices from other fields will call. It’s easy to imagine the book on leadership, the one business owners and team leaders will devour, but you suspect Klopp may find something that will surprise us all.

It won’t be politics, though. Campbell’s letter was a kind of confession, a testament to the failures of his own profession.

No doubt he wrote with tongue in cheek. But he might as well have asked Klopp to take over at Burnley.