AS the media questions began to arrive thick and fast about Ben Woodburn, now officially Liverpool’s youngest goalscorer at 17 years and 45 days, a weary-looking Jürgen Klopp tried to deflect and dampen to no avail in the post-match press conference.

Like everyone in the room, and the millions watching at home, the Liverpool manager knew he was fighting a losing battle. Whatever he said off the pitch, the story had already been written on it.

Klopp knows: football’s professional hype machine loves the wunderkind — the teenage prodigy, the child superstar.

And let’s not just blame ‘the media’ because fans do, too. It appeals to the romantic; it slices through the snideness that latches to modern football from fans that have grown weary to its ways.

There’s always been something special about watching the barely-out-of-school skinny kid yet to buy his first razor take to the pitch and fill a role despite not being able to fill a shirt.

So when a kid of 17 breaks a long-standing record at a club as big as Liverpool, moving Michael Owen — damaged image or not, eighth in the list of all-time top goal-scorers for the Reds — to one side in the process, the headlines will inevitably follow. And they have.

So it is everywhere and was always going to be: Woodburn on every back page, pictures of him as nine-year-old in a Liverpool kit, debate about whether the kid from Tattenhall in Cheshire will play for England or Wales and details of his wages.

It’s easy to get caught up in it. Who doesn’t love a goalscorer? How far can this kid go? Can he put them away like Owen did? Like Robbie Fowler did? Like Ian Rush did?

Not unreasonable thoughts, because what a story that would be. And football without stories is nothing more than men kicking a ball. Yet the more level-headed among our number will nod, enjoy it, but advise caution at this early stage of Woodburn’s football education.

Behind the scenes, it seems, Liverpool have been thinking the same. Woodburn’s name has been on the lips of fans for some time now, not least after an impressive scoring display against Wigan in pre-season that had quicky followed a goal in the friendly against Fleetwood Town.

Then, shortly after taking his GSCEs at Rainhill High, and still aged 16, Klopp ridiculed suggestions that he could play in the first team this season. To prove the point, Woodburn was left at home as Liverpool toured America in pre-season. From one moment shining so bright, to immediately back in the darkness.

Since then, the Woodburn story bubbled without boiling over. Goals — for club and country — have popped up on social media as he has gone about his business but there was no clamour for his immediate involvement in the first team.

Meanwhile, he signed his first professional contract earlier this month, the first player — it has now emerged — to see his opening pro deal capped at £40,000 per year as per the publicly-announced salary ceiling for youth team graduates.

That news aside, it seemed fairly clear Liverpool were trying to control the story around Woodburn and keep him out of the limelight.

It worked — until his debut in the Premier League vs Sunderland and his first goal in the League Cup quarter-final with Leeds United. Now? You can guarantee anyone who has ever met him in the football world is being quizzed by someone somewhere.

It appears that the teenager’s performances and attitude behind the scenes have twisted the arm of Klopp, and the brain trust he surrounds himself with, that the time was right to play him. Good enough, old enough. The old adage.

Still though, as Klopp stressed, it makes sense to try to harness the hype. It’s a couple of substitute appearances and one goal. There is a long way to go, a lot to prove and lots of questions to answer. Not least where his next minutes at the top level come from.

Liverpool has had its fair share of starlets down the years, but for every Michael Owen, Steve McManaman, Robbie Fowler, Steven Gerrard or Jamie Carragher there has been a John Welsh, Richie Partridge, Adam Morgan or Jordan Rossiter.

Rossiter scored his first — and only — Liverpool goal with a long-range strike in the League Cup tie at home to Middlesbrough on September 23, 2014 (below).

Then like now, the plaudits arrived, the background pieces were written, and everyone emerged from the shadows to tell of their part in a job well done in unearthing the great Scouse hope.

Two years on, the lad from Liverpool is plying his trade 218 miles north at Glasgow Rangers.

Many more burn brightly then fade away.

Reporting on the tragic tale of the late Wayne Harrison, a 17-year-old who Liverpool paid a then record £250,000 fee for a teenager to Oldham in 1984, The Independent reported in 2013 that former players’ charity XPro estimates that just two per cent of footballers who sign for a club as a professional are still playing beyond the age of 21.

This isn’t to spoil the moment for a teenage striker who has enjoyed a dream moment at Anfield, or to pour cold water on fans excited by a new prospect emerging from the Red ranks.

Instead, it emphasises the difficultly of the job for the player, and for those behind the scenes.

Expectations have to be managed, players have to remain mentally focused and clubs have to ensure lads who are immature in every aspect of life stay on the right track and don’t get waylaid by thoughts of having ‘made it’.

It must be a difficult balancing act. Deciding what is right for the player and his development, and when it is right to tap into the talent and help achieve what everyone desires — Liverpool winning football matches — can be no easy task.

Another of the names above, Adam Morgan, is now plying his trade at National League North outfit Curzon Ashton.

Still only 22, Morgan recently admitted in an interview with The Liverpool Echo that his “head had fallen off” after he was told by Brendan Rodgers he wouldn’t make it at Anfield.

Morgan signed for Yeovil Town after Liverpool and was then loaned out to Scottish side St Johnstone.

From there he moved to Accrington Stanley before spells with non-league Hemel Hempstead Town and Colwyn Bay.

He told the Echo: “Mentally, I was shot to bits.”

Too often there have been tales of players who spiral out of control when the dream doesn’t unfold how they imagined. And too often the attitude ermerging from football is that is a problem for the player alone to deal with.

So when Morgan revealed in the same interview that Liverpool Academy director Alex Inglethorpe had been a “massive help”, messaging the player and inviting him to the academy when he was in a dark place, it suggests Liverpool are getting things right.

The club should be ruthless in its pursuit of trophies but the balance is managing minds and treating players like human beings — before, during and after time with the club.

Klopp’s frustrated attempts to control the hype around Woodburn show he is more than aware of the conflicting challenges at his door.

It’s a dilemma made no easier by the standard of football on offer for those not quite ready for first-team football week in week out.

Once upon a time Liverpool players would be prepared for their first-team bow with lengthy spells in the reserves; the difference being the now defunct Central League was a competition worthy of the name.

The club and the players took pride in it, and any youngster looking to make his way in the game would find himself rubbing shoulders with a string of senior players, from those returning from injury to those out of favour and looking to make their mark.

Whichever, it was no easy ride — it was a test, and an indication that the player was ready.

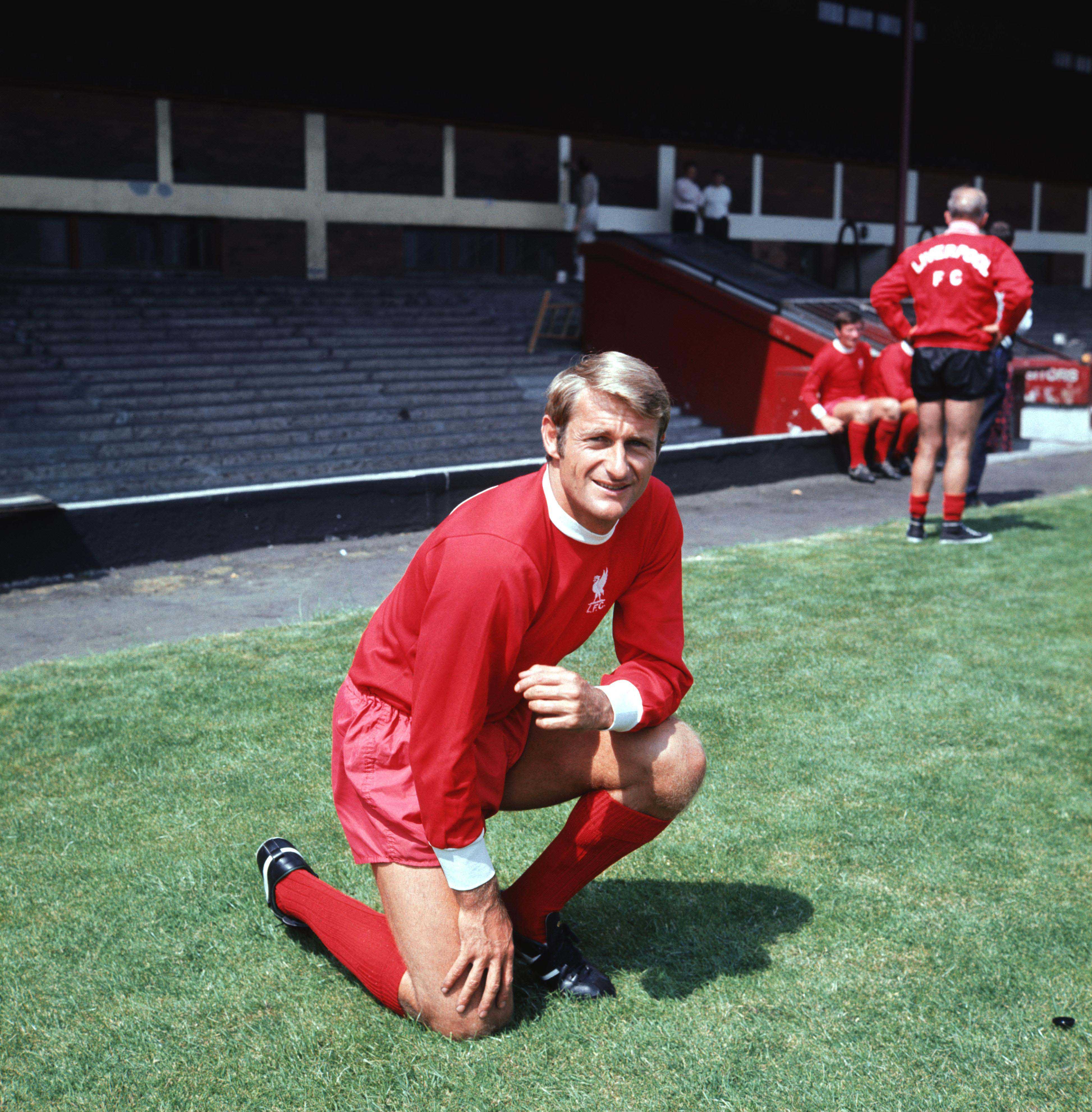

Talking of his first chance to shine in the Central League, ‘Sir’ Roger Hunt said: “All the players were pros — they were dropping a pro to play me — and I remember walking into the dressing room and one said to another, ‘I wouldn’t stand for that, being left out for an amateur!’.

“It was really competitive and we played Preston in a big important match. If we beat them you were paid a bonus.

“I scored the first goal but the pace of the game was too much for me — I wasn’t as fit as them. I was playing football but not to this intensity. Joe Fagan was the manager and I remember he came over to me at half-time and said, ‘I want more from you’. I was struggling to breathe!”

This isn’t just deep and distant past, either.

When Liverpool signed Patrik Berger in 1996, his first Anfield action was reserve-team football in the Pontins League. Lining up alongside first-teamers including Jamie Redknapp and Neil Ruddock, the Czech star scored against Nottingham Forest’s second string in front of a near 10,000 crowd at Anfield. It’s not a game with the kids in front of a crowd that is more empty seats than people at Prenton Park, is it?

The Under-23 League (clubs can field three ‘over-age’ players in each match) just cannot be considered in the same way. The Premier League describes the competition on its own website as “a new competition that replaces the Under-21 Premier League from 2016/17, with a greater focus on technicality, physicality and intensity to bring players as close to first-team experience as possible.”

How they ensure that is the case isn’t made clear, and a clear indicator that Klopp and co do not think squad players are seeing enough quality competitive football is the amount of friendlies and behind closed doors games being organised at Liverpool these days.

Huddersfield, Bradford and Accrington Stanley have all faced senior Liverpool sides at Melwood this season, while the Under-23s have faced Odense, Brentford, Qatar Under-20s, Kilmarnock and Runcorn in mid-season friendlies.

FC Nurnberg and Wigan Athletic will make the trip to Merseyside for two more friendlies booked in for December.

We’ve also witnessed loan deals fall through as loaning clubs have refused to bow to Liverpool’s insistence that players play in a certain number of matches.

It begs the question that if England was able to find a formula for competitive second-string football would Woodburn, and fellow breakthrough kids Trent Alexander Arnold (18), and Ovie Ejaria (19), be under the same spotlight they will inevitably be from now on having played for the first team at a tender age?

Klopp is used to a system in Germany that allows clubs to enter reserve teams into the league set up, although they are not permitted to compete in the top two divisions.

The problems that can potentially create is a piece in itself, and has been evidenced in England with the #B-TeamBoycott around the EFL Trophy.

But it is also perhaps recognition that young footballers need competitive football to develop.

Woodburn has been jumping age-groups because of his ability before he reached the stage that Klopp was confident he could have a chance with the first team. But for those below him on the rungs to the top, not just at Liverpool but across the country, how do they get a true chance to shine when their only competitive action is neither frequent enough or, arguably, competitive enough?

Bob Paisley famously tested Ian Rush’s mettle by claiming he would sell him in his early days at Liverpool and Rush reacted with a glut of goals for the reserves that earned him a first-team place.

Like Hunt, Rush still highlights the Central League in his formative Liverpool years. In Rush: The Autobiography, he says: “The Central League was of a very good standard of football. First Division clubs such as Liverpool, Everton, the two Manchester clubs and Leeds United would name 13 players for the first team on a Saturday; those that didn’t make the 13 played in the Central League side, which often included first-team players coming back from injury. I found I was coming up against international players on a weekly basis.”

Klopp is doing his level best to show Liverpool’s youngsters there is opportunity — that you can shine at Kirkby and Melwood and make the step up.

Yet he must harbour frustrations that his plan to nurture players as part of a group rather than an individual faces so many hurdles he has little control over.

In the meantime, it’s likely Klopp will continue to blood youngsters earlier, and more frequently, than many other managers would dare.

10 – The 10 youngest debutants under coach Jürgen #Klopp with @BenWoodburn from @LFC. Talent. pic.twitter.com/dEKyWvPC8q

— OptaFranz (@OptaFranz) November 30, 2016

Woodburn joins a list including Connor Randall, Ryan Kent, Trent Alexander Arnold, Ovie Ejaria, Sheyi Ojo, Kevin Stewart, Danny Ward, Joe Maguire, Cameron Brannagan, Pedro Chirivella, Brad Smith, Tiago Ilori and Sergi Canos in tasting first-team action under Klopp.

Where he will rank in that list in term of achievements in 10 years’ time no-one knows.

Woodburn should be given time and space to develop. He should be recognised for not only being Liverpool’s youngest goalscorer of all time but for also what he is: a 17-year-old lad with 25 first-team minutes under his belt and a long way to go to prove his worth.

- Want to hear more about Liverpool’s up and coming stars? Listen to The Anfield Wrap’s fortnightly Central League show on TAW Player.

Hi Robbo,

I think it’s £40,000 per annum not per week.

Cheers

Yes you’re right, mate. Have changed that.

Great piece Robbo, and the link to the Independent too – interesting stuff.

£40,000 per week…i’m pretty sure you meant £40,000 per year.

Great article though, completely agree we should be excited but temper it a little and just watch him develop.

Yes, it says per year. Was changed earlier.

What a heart-breaking tale Wayne Harrison’s is.

The Daily Mail once placed him on a list of ‘worst ever teen transfers’. The absolute STATE of that paper.

Decent read .. but still early doors .. buy he’s a good kid and a very good player .. only time will tell ..

Any idea why Trent hasn’t made that Opta list? Unless you count his friendly under Rodgers. I wouldn’t.

Trent has not played in the Premier League yet; Opta is probably going by first league appearance.