HILLSBOROUGH changed irrevocably the lives of 96 families, and thousands of survivors, writes DAVID WEBBER. It was, as Neil Atkinson has powerfully and rightly argued, a national disgrace. It prompted a cover up to which successive governments would be complicit, and denied justice for 27 years to the families of loved ones whose lives were cruelly cut short.

Hillsborough also brought with it the slow and sickening realisation to fans of other clubs that it could have been them. That’s the idiocy of those who mock the disaster today. They are simply fortunate that their club did not make the semi-finals of the FA Cup that season. That they were not sent to Hillsborough. They were not allocated the Leppings Lane End. Yet Sheffield’s so-called ‘Wembley of the North’ was not alone in its dilapidation. Such was the terrible state of Britain’s decrepit, overcrowded, and poorly policed terraces, many fans had feared the tragic events of April 15, 1989 unfolding somewhere.

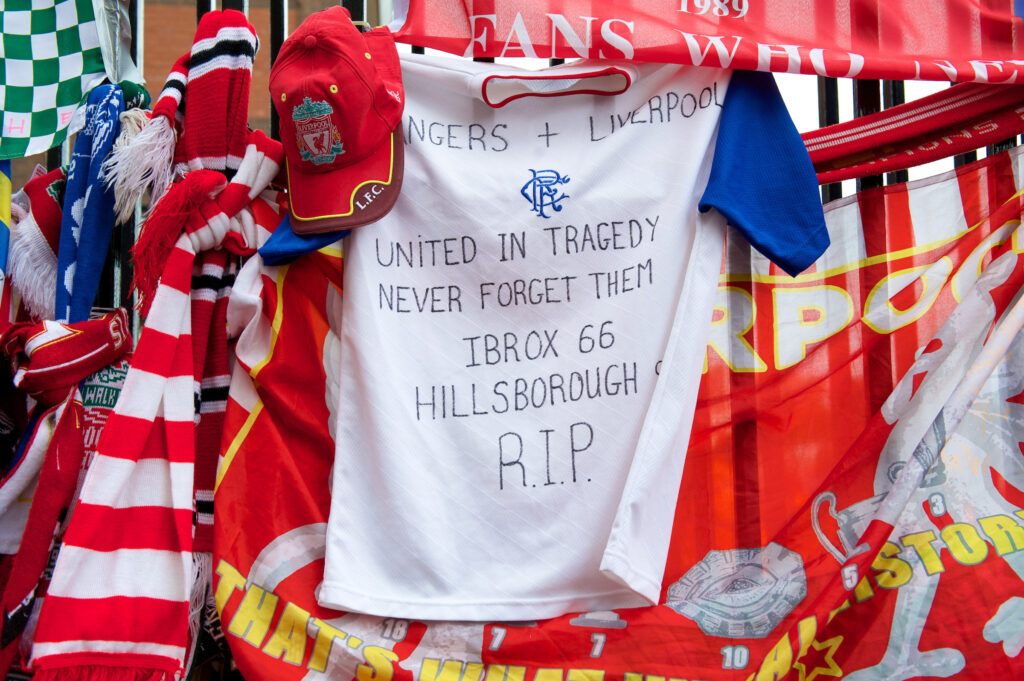

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Sunday, September 23, 2012: Tributes left at Liverpool FC’s Shankly Gates before the Premiership match against Manchester United at Anfield. The release of the Hillsborough Independent Panel’s report shed light on one of the biggest cover-up’s in British history which sought to deflect blame from the Police onto the Liverpool supporters. (Pic by David Rawcliffe/Propaganda)

But even after the fire at Valley Parade in 1985, and the experiences of Leeds United fans two years later, whenever such fears were raised they were simply dismissed. Prior to Liverpool’s fateful semi-final tie with Nottingham Forest, the club’s then Chief Executive, Peter Robinson, contacted the Football Association, pleading with them not to house the travelling Reds in the much smaller Leppings Lane End. If he was ignored, what chance did ordinary fans have in articulating their concerns?

The authorities were animated more with the spectre of hooliganism, and this loomed large over attitudes towards football fans. Fans were not to be listened to but to be controlled. The sins of a few meant that all football fans were collectively caged like animals in creaking, crumbling pens surrounded by perimeter fencing.

For those responsible with managing matches, maintaining law and order was far more important than ensuring the welfare and wellbeing of supporters. Even in the aftermath of the disaster, as the deceased lay in a makeshift mortuary, victims as young as 10 were tested for alcohol, as if this was a contributory factor. The narrative of hooliganism and ‘drunk, ticketless fans’ provided the police with a convenient, if fraudulent, alibi to cover up their own incompetence and wilful neglect of human life. It was a deceitful lie repeated unashamedly and with relish by certain parts of the tabloid media, unrelenting in their support for Margaret Thatcher’s incumbent Conservative government.

The Taylor Report, the public inquiry into the disaster published in 1990, went some way in clearing the behaviour of Liverpool supporters at Hillsborough. However, after pressure applied by Thatcher herself following the release of the interim report, the final version stopped short of criticising the conduct and the culture of the on-duty police officers. Taylor focused instead upon Britain’s decaying terraces, ordering that they be modernised and transformed into all-seater stadiums. For the 27 years, the truth remained buried, and the authorities maintained that the Taylor Report contained all the lessons that needed to be learnt.

Now, the 14 landmark verdicts delivered at the Hillsborough inquests — including one declaring the 96 deaths unlawful killing, and another exonerating the behaviour of the Liverpool fans — not only vindicate the 27-year struggle for justice but also reveal the limitations of Lord Taylor’s original inquiry.

Taylor was right, of course, to absolve the Liverpool fans of any blame and he was right to criticise those who sought to pin culpability for the disaster upon anyone other than those responsible for the fans’ safety. But Taylor stopped short of properly holding to account those who had neglected their public and legal duty of care. By emphasising the need for all-seater stadiums, Taylor’s recommendations unwittingly supported the narrative that the fans were to blame.

Football has undergone a radical and much-needed transformation in the decades since Hillsborough. Futuristic, space-aged stadiums have replaced the pre-war relics that existed at the time of the disaster, and fans can now enjoy the game in relative comfort — albeit at a considerably higher financial price.

Yet supporters still find themselves subject to a series of draconian measures designed to curb and control their movements and behaviour. Measures that stem from the same attitudes that had been significantly responsible for the failures leading up to and during the disaster and attitudes that framed the lies peddled as ‘the truth’.

With these new verdicts delivered, now is the time to challenge and change these deep-seated and duplicitous attitudes, particularly regarding standing, terracing and the consumption of alcohol. So far, in England at least, ‘safe standing’ remains a controversial issue. Rejected by the government, principally (and somewhat ironically) out of respect for those who lost loved ones at Hillsborough, safe standing has nevertheless been shown to provide a far safer alternative to the all-seated stadiums recommended by Lord Taylor.

It needs to be stated that modern safe standing does not mean a return to the dark days of the huge, crumbling terraces and the lethal perimeter fences that penned supporters in like cattle. With a safety barrier on every row and rail seats that can be bolted upright, spectators can stand safely without the threat of crushing, overcrowding, or falling over the seats in front of them.

This technology has been successfully and safely introduced in Germany, Sweden and Austria — yet there remains a reticence amongst politicians and the game’s authorities in Britain to engage constructively with those who want to be able to stand safely. Even in the light of what the Hillsborough inquests uncovered, there is an frustrating unwillingness to prioritise crowd safety over crowd control.

The same attitude is evident in the disingenuous efforts to rid football of alcohol. The use of ‘dry trains’, where the sale and drinking of alcohol is forbidden on designated routes, and the continued ban on alcohol ‘within sight of the pitch’ (a law only applicable to football matches) implicitly fuels the myth that drink and drunkenness were contributory factors at Hillsborough.

There is little evidence to suggest football’s illogical approach to alcohol — again introduced by Thatcher’s government in the mid-1980s — actually has any effect upon violence. Equalising the regulations concerning drinking during matches with other sporting events would address the discrimination that football fans continue to face and, crucially will help erase the pernicious lie spun following the disaster that drink was to blame.

After 27 years, these new verdicts finally deliver what the families and survivors of Britain’s worst sporting disaster have always known: that their loved ones were unlawfully killed, the behaviour of those who survived was beyond reproach, and there was a cover-up to protect those who had failed in their duty of care. Their long march to justice is not yet over but the painful findings of these inquests can at least begin to bring some comfort and closure to those who have campaigned for the truth with such dignity and resilience.

That it took the families so long to reach this momentous stage is testament to their courage and determination. However, it is also a damning indictment of a political system that for more than a quarter of a century denied the families and survivors of the tragedy the real truth of what happened on that Saturday afternoon in April 1989.

Britain and the rest of football owe those who fought tirelessly on behalf of their loved ones, a debt of gratitude. They challenged and called into question the attitudes of those who govern both our society and the game that is woven into the cultural fabric of the country.

These attitudes now need to change. Football’s authorities, clubs, fans and the rest of society need to change the narrative that hindered the families’ struggle for the truth, reproduced the lies of Hillsborough and denied dignity to those who lost their lives.

Only then will lasting justice be finally delivered for the 96.

Well written, well said.

I’m having a very difficult time understanding how on Earth The Anfield Wrap could have the insensitivity in this moment — so soon after the Verdict — to give voice to the subject of ‘safe’ standing. It was stated quite firmly by a Hillsborough family member in one of the two press conferences held by the families immediately after the Verdict was announced that ‘safe’ standing will NEVER be supported as long as these families and survivors of Hillsborough are alive.

It’s an abomination to try to use this moment to advance an agenda being put forth mostly by people who were not even alive 27 years ago. An agenda by people who have probably not taken a minute from their self-focused little lives to read and listen to the actual testimony of what happened to the people who stood on those Leppings Lane terraces and watched helplessly as the life was squeezed out of their family members and friends right before their eyes, as the tiny blood vessels in their internal organs exploded causing petechial hemorrhaging throughout their bodies, even as they felt their own terrifying inability to breathe, to move, to save themselves.

Choosing to publish this — and perhaps therefore endorse it (???) — at this very delicate time has given me pause to rethink my attitude toward The Anfield Wrap’s editorial practices. I’d be the first to say that everyone has the right to have their voice heard. However, this still very painful time — when it is not yet known whether there will be any substantive accountability for those who allowed and perpetuated the conditions in the Leppings Lane end — is certainly not the time to pour salt into a wound that is far, FAR from healing, and that will probably not be healed for at least the duration of another generation.

Thank you for your comment Ellie, and I apologise if the piece appears insensitive. That was certainly not my intention but hopefully I can address some of your concerns.

I was not at Hillsborough. I was 8 years old when the disaster happened and remember distinctly my Dad telling me and my brother that something terrible was happening at Hillsborough. It was a strange feeling because it was clear from just how upset my parents were that football suddenly, and what felt like the first time as a young kid, didn’t seem to matter. I’ll never forget my brother, an Everton fan, not being particularly bothered by the fact that they had just beaten Norwich in the other semi-final. It was a strange feeling. Of course, it pales into insignificance compared to the grief, hurt and anguish experienced by those who did lose loved ones but it is a feeling that has never left me. Football, supporting Liverpool, was never the same after then. It lost its innocence. No matter the highs and lows of following Liverpool over the past 27 years, I have never stopped thinking of the 96 Reds who went to a football match, never to come home. I now have a young family and it breaks my heart all over again, when I read of those who lost loved ones, whose lives were never the same again because of what happened at Hillsborough.

With this in mind, I am acutely aware that a number of the families have voiced their opposition against safe standing. I completely respect that, and I also appreciate that this remains a sensitive time for all connected with Hillsborough. The wound of losing a loved one, or even loved ones, combined with the lies, the attacks and the 27 year wait for the truth to be officially acknowledged that they have each been subject to, will never go away.

What I sought to show in my piece however, is that all-seater stadiums have been a convenient way of whitewashing the culpability of those who failed in their public duty of care on that fateful afternoon. It was not standing that caused the deaths of 96 Liverpool fans. What was made abundantly clear in the Taylor Report, the findings of the Independent Committee and now, the inquests, is that it was a lethal combination of poor policing, an inadequate response by the emergency services, and Sheffield Wednesday’s unsafe and derelict terraces that was to blame for the horrific loss of life, described in your reply.

These factors should have been the focus of the original public inquiry. However, because the government did not want the police to be made culpable, Taylor blamed football’s crumbling infrastructure instead. It was a political fudge. All seater-stadiums were introduced as a result, and the police chiefs, responsible for the disaster and who should have been prosecuted then for unlawful killing, were instead let off the hook.

It is a myth that all-seater stadiums are the safest way to watch football, There have been a number of disasters around the world (Ellis Park in Johannesburg where 43 people were crushed to death; the Accra Sports Stadium in Ghana where in 2001, 127 died falling on stairs trying to leave this all-seater stadium to name just two) that seating was actually found to directly contribute to.

Safe standing is, as its name suggests, a far safer way of watching football. We are not talking about a return to the days of crash barriers, crumbling terraces and perimeter fencing. As I hopefully make clear in the piece, safe standing prioritises above all else, safety. Had the police operation been properly managed, Hillsborough would not have happened. It was not standing fans who were to blame.

I have no agenda but justice for the 96. I don’t want to see safe standing for any other reason other than it will finally clear the names of those who were at Hillsborough. I chose my words carefully but if you believe the correct response to Hillsborough was to introduce all-seater stadiums you are following the ‘official’ line trotted out for the last 27 years. Moreover, you are implicitly blaming the standing Liverpool fans for causing the deaths of their fellow supporters. Not only is that deeply offensive, it is, as these inquests have found, simply untrue.

Plenty of Liverpool fans support safe standing, of all ages, including fans who were at Hillsborough.

Dave, thank you for responding. I thought your article was indeed carefully written. It was reasonable and respectful in its tone. I’m sure you are correct that there is good evidence to support arguments in favour of modern-day standing terraces. Your last sentences, however, are COMPLETELY wrong and quite insulting toward me. They are a twisted version of the Verdict’s exoneration of the fans. But I’m not going to use this comment thread to try to discuss that because it is not what motivated my comment.

The motivation for my comment is that there is a whole generation of people who were at Hillsborough who still suffer profoundly with the memory of what they experienced. They mostly suffer in silence or share their thoughts and feelings with only a select few who they are certain they can trust. The sight and sound of a swaying crowd at a football match is unbearable. They will never be able to bear it without enduring floods of memories of that terrible day. They will never be able to take their children anywhere near it. They think about it every time they approach the turnstiles. They struggle to even know how to talk to or explain it to their young sons.

It’s about human beings, the long-term effects of a trauma that cannot be erased, the way it continues to pop up and affect the psyche in ways that other people can never imagine or understand. My comment was a plea for sensitivity for what those people endure. It’s still far too raw. And that’s not even mentioning the Families of the 96 who were only recently forced yet again to endure reliving their tragic loss by way of the excruciating detail brought out in the Inquest testimony.

And as far as the other comment goes, it’s simply not relevant in terms of the point I am attempting to make.

It’s just your opinion. Nothing more. You are speaking for yourself.

One more little bit, Dave. It’s not about a rational conversation regarding technology or design or engineering or materials. It’s about what standing represents; it’s about the association. I hope you can try to step outside your personal desire and see and try to feel it from another person’s point of view.

And that’s what it is. Your point of view.

No, actually it’s not. I was not speaking about myself in my last sentence. Those who have an open mind would do well to learn something about how the human brain responds to trauma, how trauma is irreversible due to changes in brain chemistry (though coping mechanisms can be learned), and how using logic has no impact on the brains of those who have endured life-altering trauma.

In any case, the law might change to allow ‘safe’ standing at some future time, but it’s very unlikely it would be mandated for all stadia. And as long as there are mothers and fathers alive on Merseyside who lost their children at Hillsborough it is highly unlikely that ‘safe’ standing would be broadly adopted at Anfield. I can’t think of a worse slap in the face after 27 years of Hillsborough Memorial Services being held in that ground.

Again, I would beg to differ Ellie. This is, I am fully aware, a hugely emotive subject. However, that does not mean we cannot look rationally at the issues. Standing did not cause Hillsborough, ergo, to introduce all-seater stadiums was not the correct response to the disaster. The correct response was to hold to account and bring prosecutions against those responsible for managing the game. The government did not want that to happen and the blame was shifted instead onto the infrastructure. The media (and sadly, some fans of other clubs played their part) in also blaming the fans but both were based upon a prejudiced reading of the events of Hillsborough.

You also appear to conflate safe standing with the open terraces of Hillsborough, the old standing Kop and every other large terrace of the 1970s and 80s. That is not what safe standing is about. You may find this page helpful in distinguishing between the two. It also highlights the safety features that safe standing promotes. http://www.fsf.org.uk/campaigns/safe-standing/what-does-safe-standing-look-like/

Great article, some good points well made. That’s just my opinion, I don’t represent anyone who was present that day.