FROM a position of weakness, the first thing a manager usually tries to do is help the side he has inherited become tougher to beat than it was before.

FROM a position of weakness, the first thing a manager usually tries to do is help the side he has inherited become tougher to beat than it was before.

Brendan Rodgers attempted to make Liverpool more attractive to watch, so when the criticisms came — that Liverpool were too flaky — a new focus on defending felt like regression; certainly not something to really get excited about and, rather, something the manager should have been delivering as a matter of course.

Rodgers was unlike a couple of his predecessors: those otherwise comparable managers who started their coaching careers in lowly positions and through courage in their convictions, made their way to the top using talent and sheer force of will.

Gérard Houllier and Rafael Benítez were similar in that sense: a pair who did not have anything to trade at places like Nœux-les-Mines and Extremadura and therefore appreciated the only way forward was to find a way to stop the opposition rather than beating them with what they had in attack.

Their careers had been intertwined to some degree, with experience of shaping a defence and building from there. Houllier did it with Lens in France and moved to Paris Saint Germain to win the league, while Benítez did the same thing at Tenerife before he fashioned Valencia into a title-winning team — one that also included exciting flying wingers, tricky playmakers and bustling centre forwards.

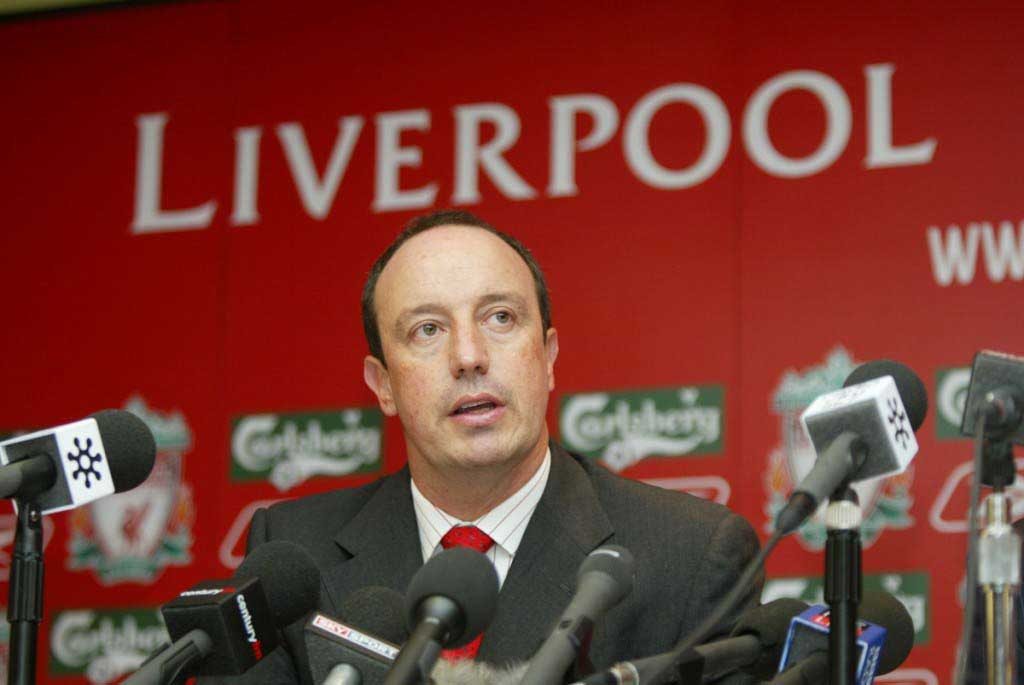

It explains why Benítez replacing Houllier made absolute sense when that changeover happened in 2004.

It explains why Benítez replacing Houllier made absolute sense when that changeover happened in 2004.

The Spaniard had just achieved what Houllier aspired to achieve by toppling a couple of clubs with greater financial means domestically. He had done it through the same devotion to his work, meticulous planning and sharp recruitment that Houllier had shown before his edge fell away after returning to the Liverpool job following illness.

When Benítez arrived at Anfield, a solid enough defence was present — one that knew its responsibilities but had room for improvement. By moving Jamie Carragher into the centre and leaving him there, Benítez made the defence better and if that doesn’t happen, I wonder whether Liverpool end up winning the Champions League a year later.

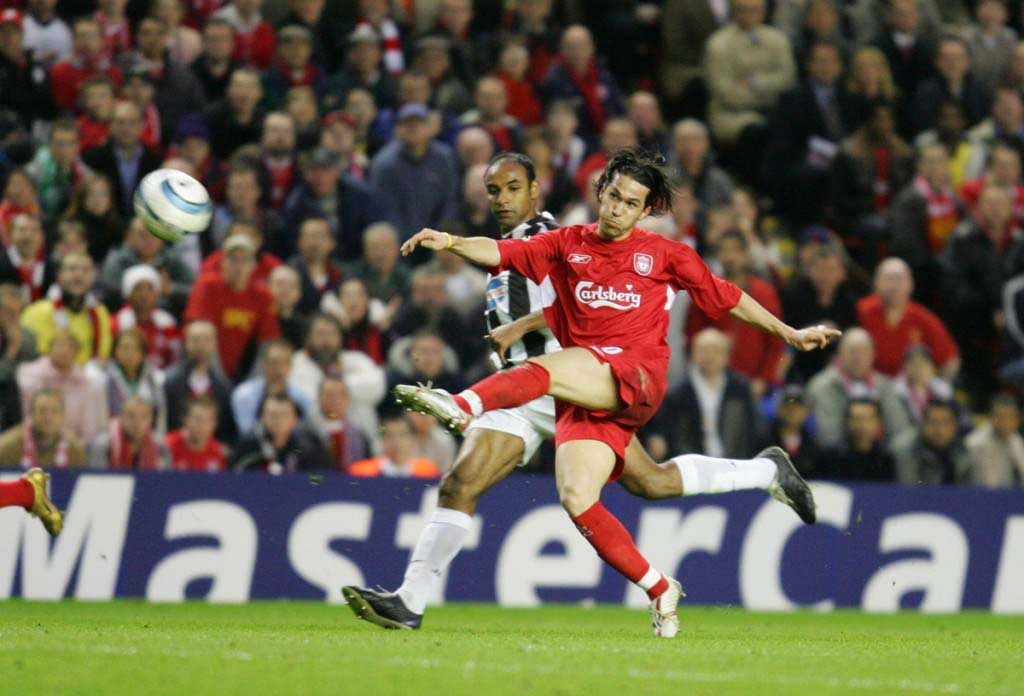

And yet, Benítez’s Liverpool was built on more than defence. What got Liverpool through the rounds in 2004-05 was a mixture of everything: Benítez’s tactics, his planning; Steven Gerrard’s brilliance at key moments and Carragher’s leadership — speaking up when something really needed to be said, both inside dressing rooms and out on the pitch.

Then there was influence from Luis García, Didi Hamann, Xabi Alonso, Neil Mellor and Florent Sinama Pongolle.

Each person involved performed some role — the fans, too.

They always ask what helped Liverpool beat Chelsea in the semi-final, trying to pinpoint on individual.

They always ask what helped Liverpool beat Chelsea in the semi-final, trying to pinpoint on individual.

Maybe García’s goal went in, maybe it didn’t.

Maybe the officials simply panicked and bottled it under the pressure from the home support on the terraces.

If that game takes place in front of an empty stadium, is the outcome the same?

What changed the most, perhaps, was the mood — the mood that Liverpool could recover from impossible positions, that Liverpool were never beaten, even when the scoreline is 3-0 in favour to the best club side on the planet and the best club side on the planet is not Liverpool.

It is a powerful, though unquantifiable quality: the ability to recover.

The only statistic that measures it is the number of times you do it. No statistic can really detail what prompts it to happen, so the natural conclusion ends with the part of the manager.

Benítez helped change the mood. Speak to those around him at the time and they recall him asking, as if it should naturally be happening: “Well: why can’t Liverpool win the Champions League?”

Liverpool’s current only hope of silverware is the Europa League and the Europa League is not the Champions League. From here, if Jürgen Klopp achieves the same improbable results all the way to the final, it will not be remembered in the same way.

Liverpool’s current only hope of silverware is the Europa League and the Europa League is not the Champions League. From here, if Jürgen Klopp achieves the same improbable results all the way to the final, it will not be remembered in the same way.

That would not make his work any less impressive, however.

When he arrived, Liverpool were a Europa League club and he is working with exactly the same set of players plus Steven Caulker.

The German could only do his best with what was set in front of him.

Like Benítez in 2005, Klopp has already reached a League Cup final and lost, albeit on penalties after the game in normal time was rescued when it felt like the outcome was already settled for Manchester City.

Unlike Benítez, however, Klopp has been saddled with a disjointed squad put together by a previous manager and a transfer committee with different ideas — though not opposites — about how the game is played.

Consider the atmosphere inside Anfield when Klopp was appointed. When it seemed like Liverpool were beaten, they were beaten. There was nobody to trust, certainly among those playing; that someone involved could help salvage a wreckage of a game like Crystal Palace on Sunday.

Unlike Houllier and unlike Benítez, Klopp has not constructed any strength and confidence from the defence — largely because he has not yet been able to.

The only constant has been Nathaniel Clyne who, in the fullness of time, will probably look back on his debut Liverpool campaign with some satisfaction.

Due to injuries, Klopp has not settled on a combination in the middle and that must worry him because consistently injured centre backs are no use to anyone — especially in a position where consistency is paramount to the performance of the team.

Klopp has already recruited Joël Matip for next season so, clearly, he has realised this. Meanwhile, maybe at some point in the future, an opponent will be seen dribbling the ball in a dangerous area near Liverpool’s left back position and Alberto Moreno will be there.

This, surely, is another position marked for improvement.

Question marks all over the pitch remain. Liverpool have been without assurance at the back and with a goalkeeper who will never be able to convince because too much has happened for things to change.

In midfield, Liverpool have frequently been unbalanced and there is nobody behind Philippe Coutinho to supply a quick pass, which often leaves the Brazilian frustrated.

Klopp has already stated he will look to improve in the wide areas, too, where pace is not married with tactical understanding.

Despite all of these issues, Klopp has found a way to instil belief. In 11 games since his appointment, Liverpool have retrieved something from games where they have fallen behind.

It explains why, at a time of wider uncertainty, one of the question marks does not relate to the person who resides in the manager’s office.

Wonderful article and good insight into the Roders-Klopp-Benitez comparisons.