WITH the paperback version of Men In White Suits released this week, The Anfield Wrap has an exclusive full chapter extract from the book, where Graeme Souness speaks candidly to Simon Hughes, admitting where he got it wrong during his turbulent time as Liverpool manager.

It should not be like this for Graeme Souness, explaining where it all went wrong.

Souness should be in line with Kenny Dalglish and Steven Gerrard whenever Liverpool’s greatest post-war players are mentioned. Yet he took a risk on his reputation and, as he puts it, “blew the chance”.

He dismisses my suggestion that he might regret accepting the role of Liverpool manager, “No, no, no, not at all.” Yet he stresses the problems in 1991 were greater than anyone really appreciated. “Listen,” he continues, “it was a job that I felt I had to do.” Then, without any hesitation, he offers a caveat: “Though I took it at completely the wrong time.”

Souness compares the situation he inherited to the one David Moyes found at Manchester United after Alex Ferguson’s sudden retirement.

“You’ve got a club with 25 years of success,” he says. “The first manager in is a bringer of bad news, where he’s telling players — in some cases legends — that their time is up. Nobody goes quietly. There’s a period when you are not going to be successful because you are buying in players that are going to take time to settle down.

“You are asking supporters to be patient, and this is at a time when the expectation levels are still enormous. It has to be managed. For me, you don’t want to be the first one to follow Fergie, because you’ll be the one that gets all the flak for doing what would appear to be everything wrong, when it’s not really the case.

“The second one [Louis van Gaal] comes in and maybe tries to achieve success too quickly by adopting an aggressive transfer policy without any real thinking behind it. Perhaps you could compare that to Roy [Evans] at Liverpool after me.

“Ideally, you want to be the third one in, when expectation levels are back at a manageable level. Then you can build it up again.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLZ-izJAzAU

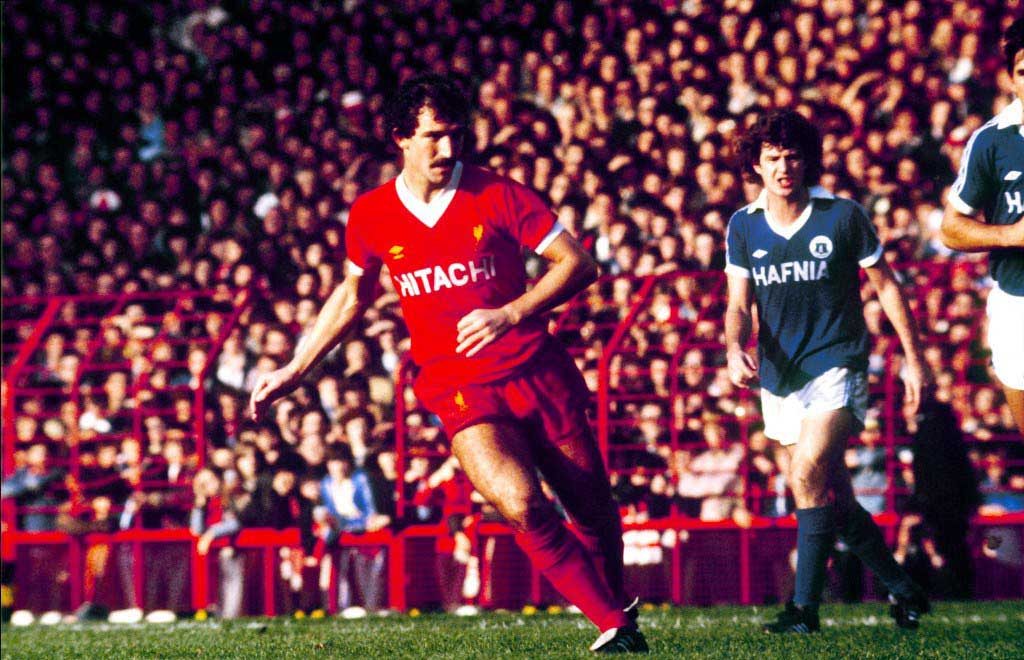

The Liverpool move seemed like the dream appointment, both for the club and manager. “I was blinded by my feelings for Liverpool,” admits Souness, who as a player at Anfield won nearly everything there was to win, both domestically and internationally. As an obdurate, iron-willed wall of muscle, he captained the greatest club in Europe before making a lucrative transfer to Sampdoria in Italy. His step up to management, at the hitherto struggling Glasgow Rangers, initiated a period of almost total dominance in Scotland.

“Since leaving Spurs as a teenager, everywhere I’d gone it was success, success, success; medal, medal, medal; trophy, trophy, trophy,” he says. ‘I thought the pattern would continue at Liverpool. I didn’t stop for a minute to think about what I was doing, to analyse the situation.”

He was not to know at the time, but his reputation would spectacularly alter. Souness the player and Souness the manager are viewed somewhat differently.

- Champagne Charlie: The Case Of Graeme Souness

- Reliving The 1980s: Did Liverpool And Dalglish Get It Wrong?

Considering his achievements as a captain — the swaggering style and spirit with which he led the team — I find it sad that he is not remembered with absolute reverence. He reminds me several times that although there are mitigating circumstances if people are willing to listen, only he is to blame for a blemished legacy.

“I know I made mistakes,” Souness says, immediately citing an interview he did with The Sun on the third anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster. The paper was hated on Merseyside after it printed lies about the role of Liverpool supporters on that dreadful April afternoon in 1989. “I will regret the decision forever. I don’t have a defence.”

Souness admits that also he took the wrong approach when dealing with players. “I appreciate that I was too hard with everyone. I’d come from a generation where the attitude to problems was just to get on with it: to look at yourself in the mirror and sort it out. As players, we were treated like men and expected to act as men.

“The thing I miss most as a player is the confrontation and the rivalry, standing in the tunnel and waiting for the battle. If we lost, I found it hard to shake hands. I’d go home and sit alone for the evening. You see a lot of players now hugging each other. They swap shirts with the opposition at half-time. It’s wrong.

“In management, I expected my players to feel the same as me. But the world was changing. Players were expecting a shoulder to cry on. The players were holding more power than the manager. I wasn’t cute enough sometimes, or political enough.”

Souness speaks in the arrivals hall of Edinburgh Airport in his home city, where he is meeting with old friends for the weekend. I had interviewed him six years earlier at Anfield as he waited to go live on air for a Sky broadcast. He is an impressive individual.

While Richard Keys and Andy Gray bantered away in an otherwise hectic room, Souness sat alone in a dimly-lit corner amongst his own thoughts. I recall a lone sliver of bright light piercing through a tinted window and crossing Souness’s tough-looking face. It made him seem like a prisoner in a war movie as he slowly, thoughtfully and confidently spoke about his experiences. He exuded an awesome aura that instantly commanded respect. I thought Souness — the only Souness in football — was made of granite.

I wondered whether he was born a leader. Like Irvine Welsh, the acclaimed and controversial writer of Trainspotting and Filth, Souness’s family came from Leith — Edinburgh’s industrial centre and dock area. Souness grew up, however, further inland in Saughton Mains, where the city’s prison is a brooding presence.

“I had a very loving and caring family background,” he tells me. “I was the youngest of three brothers, which meant I always had something to prove. When you’re around kids that are older, they always tell you that they are better at everything. I didn’t want that to be the case. It toughened me up.”

Souness’s father was a glazier and the family lived in a prefab. Between the ages of 12 and 15, Souness would sleep at his grandmother’s home in a tenement block a few miles away on Gorgie Road, where the air reeked of fermenting yeast from the nearby Caledonian Brewery.

“She was lonely,” he explains. “My grandfather had died and my brothers had cared for her before they hit 16 as well. There was no questioning; we just did it. It was our way of life.”

It did not mean Souness missed out on football. There was a big field outside his parents’ home. “I wasn’t bothered about Hibs or Hearts really, because I was always playing football on a Saturday, although Tyncastle was closer to my home. For as long as I can remember, I never thought about doing anything else. From the earliest age, the thought never entered my head that I wouldn’t become a footballer. Some people may have seen it as misguided confidence but I turned out to be right, didn’t I?”

Although he’d been captain of his school team, Souness only took the role on for the first time as a professional at Liverpool, aged 28.

“I wasn’t captain of the Spurs team that won the FA Youth Cup. I wasn’t made captain at Middlesbrough. I was a late developer, although I’d always played with arrogance.”

Coming from the same Carrickvale Secondary School as the great Dave Mackay acted as motivation in the early days.

Coming from the same Carrickvale Secondary School as the great Dave Mackay acted as motivation in the early days.

“I occasionally stood on the terraces at Hearts and saw Dave play. He was a real warrior type. I was constantly reminded by my headmaster that I’d never be as good as him.”

After playing for Scotland Schoolboys against England Schoolboys at White Hart Lane, Mackay — who was Tottenham’s captain and watching in the stands — recommended Souness to Bill Nicholson, Spurs’ legendary coach.

“Dave was the only name ever mentioned by Bill Nic. He never mentioned John White, he never mentioned Danny Blanchflower — only ever Dave Mackay. It felt like I lived with him. I told him years later that I was fed up hearing his name. But I never set out to be like anyone else. I played the game as I saw it.”

Souness insists he was more impulsive as a teenager than he is now.

“I went to Spurs at 15 and thought I was going to be a superstar,” he admits. “I was headstrong and pretty soon I was knocking on Bill Nic’s door asking why I wasn’t in the first team.” At 17, Souness was suspended for two weeks by the club without pay for taking a leave of absence in Edinburgh, citing homesickness.

He felt “completely at sea with the London scene”. By 19, he was allowed to leave for Middlesbrough. “It came as a real shock when Spurs agreed the deal. It made me more determined than ever to become a successful footballer and to prove them wrong.”

Souness’s towering self-belief and desire to win brought him more medals than an army veteran. Yet his career was fuelled not just by what he describes as “the unique taste of success” but also by the whiplash of a few failures. “No person’s playing career is full of highs,” he says. “My one real low came right at the start of mine. It kicked me where it hurt and I had to deal with it. It shaped the way I was thereafter.”

His combative performances for Middlesbrough earned him a record transfer to Liverpool in January 1978. On his first morning in the Anfield dressing room, he remembers asking Tommy Smith, Liverpool’s most ferocious player, if he could borrow his hairdryer. “Tommy turned to Phil Neal and commented, ‘Everyone is allowed to make one mistake’.”

His combative performances for Middlesbrough earned him a record transfer to Liverpool in January 1978. On his first morning in the Anfield dressing room, he remembers asking Tommy Smith, Liverpool’s most ferocious player, if he could borrow his hairdryer. “Tommy turned to Phil Neal and commented, ‘Everyone is allowed to make one mistake’.”

Liverpool had great managers. But Souness believes the team was driven towards triumph because of its senior players. “I turned up at Liverpool when I was 24. I was a bit of a Jack the Lad. At least I thought I was. Very quickly, I was put in place verbally by the senior pros. There were no prima donnas and no superstars. Any problems on or off the pitch, the more experienced boys would stamp it out.”

He was made captain upon Liverpool’s 3-1 defeat to Manchester City at Anfield in December 1981, leaving Bob Paisley’s team in 12th place in the league.

Dalglish and Neal were older than Souness and considered favourites for the role after it was revealed that Phil Thompson was being relieved of the responsibility. By the end of the season, Liverpool were champions, having toppled Ipswich Town by four points.

Michael Robinson, the striker who signed for Liverpool from Brighton & Hove Albion in 1983 before struggling to deal with the expectations of the club, said Souness approached every game exactly the same.

“The attitude throughout the club was that if we didn’t do well, anybody could beat us,” Robinson said. “If we did do well, nobody could beat us. It was humble. I remember once before a game against Brentford in the League Cup, Graeme had the dressing room buzzing like we were playing against Manchester United. There was no complacency — ever.”

Robinson also said that Souness helped him deal with his own insecurities about being good enough to play for Liverpool.

“Once you chipped off that varnish, I found Graeme a very personal, cuddly chap who was actually quite vulnerable about being a human being with emotions. To this day, he still tries very hard not to be this lovely cuddly person, when really he is.”

When asked whether he found any aspect of captaincy challenging, Souness responds before I can finish the question. “None, absolutely none,” he says. “My attitude didn’t change at all. Joe [Fagan] pulled me to one side soon after and told me to focus only on looking after my own game. I realised that if I set the example, the rest would follow.”

Souness says his greatest performance for Liverpool came in his last match before joining Sampdoria, against Roma in Rome in the European Cup final of 1984. “It felt like we’d gone to the Coliseum and sacked the place. Nobody gave us a chance. But we had the most ridiculous inner belief. Had it been Barcelona in the Nou Camp or Real Madrid in the Bernabéu, we’d have done what we had to do to win the game and done a number on them.”

He believes, however, that captaincy did not prepare him for management “one bit”. As captain of Liverpool, the responsibility was “easy because of the calibre of person and quality of player you’re sharing a dressing room with”. He reiterates that he rarely had to think about anyone else’s welfare, only his own.

Management was different.

“As a manager, I could not forget about the job — much to the irritation of my wife. It wasn’t a case of leaving the stadium and thinking about something else. I’d be thinking about it driving home, I’d be thinking about it when I got home, I’d be thinking about it when there was an interval on a television programme I was watching, they were the last thoughts in my head before I fell asleep. I found it impossible to switch off. It’s a roller-coaster ride. Not year by year, not month by month, not week by week, but day by day, hour by hour, result by result.

“If I was winning — like I was at Rangers — or if I was losing — like I was more often at Liverpool — my mind was only ever on the job. As a captain, you concern yourself with your fitness and form. When you’re a manager, you think about the welfare of 30 players. Then there are the media and the board of directors that you are answerable to.’

Souness became the first player-manager in Rangers’ history when he succeeded Jock Wallace at Ibrox in 1986, a month short of his 33rd birthday. Financed initially by the club’s then owner Lawrence Marlborough, Souness and chairman David Holmes embarked upon a bold strategy of reclaiming the foot-balling ascendancy that Rangers had been desperately seeking in Scotland after years in the wilderness due to the dominance of arch rivals Celtic and the emergence of the ‘New Firm’, Aberdeen and Dundee United.

At Rangers, Souness proved early on that he was not afraid to make difficult decisions. He capitalised on the banning of English clubs in European competition after the Heysel stadium disaster by signing numerous English players, in turn reversing decades of historical tradition whereby Scottish players moved south of the border. Not only did he revive the glory days, he succeeded in taking the most enormous and brave risks.

After Mark Walters became the first black player to represent Rangers in more than 50 years, Souness made Maurice Johnson Rangers’ first Catholic player. Souness claims the decision to sign the pair was made for practical rather than any profoundly historical reasons. “They were two good players who I thought would serve us well,” he says.

A year after Souness’s departure from Anfield, Joe Fagan retired as Liverpool’s manager. For 26 years, Liverpool’s management structure had been comparable to that of a mafia crime family. In Bill Shankly, there was the boss, Bob Paisley was the consigliere or councillor, then Fagan, the underboss. Ronnie Moran, Roy Evans and Reuben Bennett were the capos, who headed the crew of soldiers — in football terms, the players.

The organisation was put in place so that Liverpool would achieve long-standing success. Like the mafia, Liverpool was led by a group of old men who met in private in a smelly old room to discuss their plans. Nothing was ostentatious or above suspicion. There were simple and ruthless principles and no fancy purchases. In the Boot Room after games, Fagan particularly was well skilled at slapping beaten opponents on the back with one hand and extracting information for future reference with the other, much like a mafia priest.

By 1985, Shankly had died, Paisley had gone, Bennett had gone, as had Fagan — after just two seasons and sooner than anyone at the club had expected.

Liverpool’s response was to promote Kenny Dalglish from soldier level to boss. Dalglish sacked both Geoff Twentyman as chief scout and Chris Lawler as reserve-team coach and began appointing his own people. Sackings had not happened since before Shankly’s appointment. Dalglish was under pressure to achieve results while the backroom staff were being restructured. By the time he was to depart, Moran and Evans were not considered ready to make the step up. Before Souness, some traditions already belonged to the past.

On Dalglish’s sudden resignation in January 1991, Souness did not think of leaving Rangers, where he was the second biggest shareholder and had been promised a job for life under new chairman, David Murray. There had been three Scottish First Division titles and four League Cups. Only once had he come close to a move away. Had Michael Knighton completed his takeover of Manchester United in 1989, Souness would have replaced a then struggling Alex Ferguson.

Knighton had agreed to buy Martin Edwards’ stake for £10million and appeared on the pitch at Old Trafford before a game dressed in a full United kit to publicise his proposed purchase. At a meeting in Edinburgh, Knighton discussed the project until the early hours of one morning with Murray, who planned to make a considerable investment in United.

It was agreed that Souness should be United’s new manager and Walter Smith would earn promotion at Ibrox from his role as Souness’s assistant. Knighton’s acquisition, however, fell through when Murray had second thoughts. The FA were cracking down on individuals having influence in more than one club after the mess created by Robert Maxwell at Oxford United and Derby County. Chelsea owner Ken Bates had put money into Partick Thistle and, with investigations taking place, Murray was reluctant to get involved in a similar controversy. Knighton also approached Blackpool’s Owen Oyston but never completed the deal. He was later involved with Carlisle United, but the club entered voluntary administration in 2002.

Everton 4 Liverpool 4: The scars that can’t be seen

Souness received two phone calls from chief executive Peter Robinson asking whether he’d be interested in replacing Dalglish but had been informed by someone close to the board that Liverpool’s priority was to appoint from within, as they had done before. Moran had acted as Dalglish’s temporary replacement. First-team coach Evans was another contender, as were Phil Thompson and Steve Heighway, who led the reserve and the youth teams.

Alan Hansen, captain since the 1985–86 season, had just retired as a player but he ruled himself out almost immediately. Then there was John Toshack, the former striker with the most experience of management, having recently left Real Madrid.

Souness’s bond with Rangers had grown because of the relationship with his chairman. “David gave me a free reign,” Souness explains. “He was a friend and our understanding couldn’t have been any better. We lived near each other and socialised most nights of the week. These were good times: success after success. We’d turned it round there and the team was ready to have a good go of it in Europe. There was no reason to leave.”

Yet living in the “goldfish bowl of Glasgow” had its difficulties. Rangers were always under the spotlight and so was Souness. There were problems on a personal and professional level. Having separated from his first wife, he was regularly followed along the motorway from his Edinburgh home to Glasgow by tabloid reporters hunting for scandal.

By 1991, Souness was in the middle of a long touchline ban, while an incident with a tea lady had nearly led to a fight with St Johnstone’s chairman after a league match. It proved to be a tipping point.

After the first brief talks at the start of February, Souness called Robinson back towards the end of March to try to establish whether an offer was still in place.

Under Moran, Liverpool’s results had faltered and the recruitment process had stalled. Within 24 hours, Souness was meeting with Walter Smith and first-team coach Phil Boersma to tell them about his plans to quit Rangers. Souness wanted both Smith and Boersma to join him. Kirkby-born Boersma had scored 30 goals in 120 Liverpool games before joining Souness at Middlesbrough in 1975.

“Phil was a lifelong Liverpool supporter and could not have been any more excited.” Smith, who would later manage Everton, decided against it and replaced Souness at Ibrox on Souness’s advice, even though Murray wanted a higher profile name. “Walter had been my right-hand man and someone I trusted implicitly.” Smith was concerned that he might not be welcomed by Moran or Roy Evans, as their roles were similar. “I was disappointed, because it was my plan for everyone to work together,” Souness says. “But even without Walter, I’d made my mind up to go.”

Murray made a final attempt to keep Souness in Scotland by offering a blank contract where he could fill in the details himself. “The decision had been made,” Souness continues. “David warned me that going back to Liverpool would be a huge mistake. I have to admit it, he was right.”

Souness was warned about the problems at Anfield by Peter Robinson, who had been a key administrator at the club for almost 30 years and remained loyal despite several offers to join the Football Association. Robinson’s influence was so considerable that when Bill Shankly was offered the manager’s job at Sunderland following one of his many arguments with the Liverpool board in the early sixties, Shankly discussed the possibility of taking Robinson with him.

Souness had tried to sign Jan Mølby for Rangers and planned to build his new Liverpool team around the Danish midfielder and John Barnes. Robinson advised that Liverpool’s team had faded and only Barnes was capable of remaining in the long term. “Tom Saunders was also a respected figure at Liverpool and he told me as well that the challenge was greater than anyone on the outside recognised,” Souness says.

Robinson warned of Manchester United’s business potential if they ever married a successful managerial selection policy with positive results on the pitch. Within a month of Souness’s appointment, United lifted the European Cup Winners’ Cup with victory over Barcelona in Rotterdam. A year earlier, Alex Ferguson’s side had won the FA Cup in a replay with Crystal Palace, who’d beaten Liverpool in the semi. A new challenge was coming.

Souness believed Liverpool had to react quickly. It was his immediate view that many of his squad had “lost their passion for Liverpool”, and it came as a shock.

Not for the first time in this interview, Souness speaks about his expectations of “senior players” during his time as captain.

“Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan were the managers and Ronnie Moran was the disciplinarian. But the real lessons came from players like Steve Heighway, Phil Neal, Ray Clemence and Emlyn Hughes. The staff deserve all the credit for selecting the right type of person to join the squad but once they were in place Melwood governed itself. You’d have three or four leaders showing the way and the rest following, whether that’s in the match or socially. By the time I went back as manager, that culture had gone.”

Souness speaks of individuals more concerned by the value of their next contract. He refuses to name names, as he’s “made up with many of them since”, but this was a time where wages were accelerating. Ageing pros did not want to miss out on one final payday. Souness says his relationship with many of them was strained after Peter Robinson asked him whether he wanted to take charge of negotiating players’ contracts.

Perhaps Robinson felt uncomfortable in dealing with the skyrocketing sums. Liverpool had long been notoriously tight with wages and used the history and position of the club as leverage. Robinson would enter discussions with a lower offer than the player expected. Often it meant a pay cut. Robinson would exit the room and leave the player alone with his thoughts. Then the manager, be it Shankly, Paisley, Fagan or Dalglish, would enter separately, informing the player he would help him by getting Robinson to raise his offer.

This process would get the player believing the manager was on his side, immediately setting the agenda for their relationship, and leave the club paying roughly what they wanted to pay in the first place. Suddenly, however, the trusted routine was broken.

“Initially, I thought it was Peter’s way of paying me a compliment but it was my first big mistake, agreeing to it,” Souness says. “I couldn’t understand why anyone would grumble with being paid what I thought was a decent sum to play for Liverpool. Whatever I offered, they always wanted more. Liverpool was the only team I wanted to play for and I would have stayed forever had the club not accepted a really good offer from Sampdoria for me. There was no place I’d rather have been.”

You can detect the anger even now when Souness speaks about the shift in attitude and the haggling that took place.

“I should have kept them on and waited for their replacements to bed in. Instead, I couldn’t help it. I’d tell Peter [Robinson] on the phone, ‘You know what? Whoever it is, get them to call me this afternoon. They can go tomorrow as far as I’m concerned.’ That was a mistake. You’re buying under pressure then. I should have been far cuter.”

Peter Beardsley, aged 30, Gary Gillespie, 31 and Steve McMahon, 30, were the first of the most experienced players to leave, ones that with hindsight Souness wished he’d kept longer. Others, like Ray Houghton, remained. “Ray told me his wife was homesick and wanted to return to London, so I accepted a bid from Chelsea. Ray was halfway down the M6 when he called to tell me Ron Atkinson had made him a better financial offer. ‘You know what, Ray, do whatever you bloody want,’ I told him.”

Souness was happy to release Jimmy Carter, Glen Hysen and David Speedie, who were “not up to it”, though he did not want to sell 22-year-old Steve Staunton, the Irish left-back whose future was influenced by a “silly rule” that classified non-English players as foreigners and decreed that only three could play at a time.

“Steve had a beautiful left foot and could play in a number of positions,” Souness says. “The regulation was withdrawn by the FA within 12 months and that really frustrated me.”

What also made it hard for Souness was that he was telling players who had developed an emotional attachment to Kenny Dalglish and, indeed, to Liverpool in the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster that suddenly they were not wanted.

But ever since Bill Shankly had struggled with the idea of dispensing with key members of his 1960s team, leading to nearly seven years without a trophy and a humbling 1-0 defeat to Second Division Watford in an FA Cup quarter-final in 1970, Liverpool had never allowed sentiment to get in the way of decisive decision making.

“When your time was up, it was up,” Souness says. “I was a case in point. It was a transfer record between two English clubs when Liverpool bought me from Middlesbrough for £352,000. Then they sold me for £650,000 to Sampdoria. Although it also suited me to go, nobody sat me down and tried to persuade me to stay using football reasons never mind financial reasons. I was 31 years old. Liverpool figured they’d had seven years of great service out of me and they were more than doubling their money for a player who had peaked. It was ruthless business.”

After Hillsborough, the policy of moving players on before their decline became too evident understandably slipped and Liverpool’s team became a victim of circumstance.

Yet I suggest to Souness that Liverpool’s transfer policy had altered under Dalglish long before Hillsborough. After missing out on the title to Everton in 1987, and with Dalglish under some pressure, he decided to spend big. John Aldridge, aged 28, Beardsley, 26, Houghton, 25 and Barnes, 24, all arrived for huge fees. For the first time in its history, Liverpool were outspending their rivals in an attempt to keep ahead of the game and nobody seemed to mind.

The First Division championship was wrestled back in 1988 and won again in 1990. Yet behind the scenes, young players were either not good enough or had not been given the necessary exposure that would eventually enable them to secure long-term first-team football.

In Dalglish’s five-and-a-half years in charge, he signed seven players under the age of 20 that would play for the first team, promoting only Gary Ablett from the youth system. Of the seven, four left impressions that ranged from reasonable to good: Mike Marsh, Don Hutchison, Jamie Redknapp and Staunton. It meant that by the time Souness returned to Merseyside, Liverpool’s squad was made up of old players almost past their best and youngsters not ready to represent Liverpool on a regular basis.

Souness was the first manager since Shankly unable to make signings and give them time to get used to the demands of the club by playing them in the reserves first.

“Only Kenny will be able to tell you why he made certain decisions at certain times,” Souness says. “All I know is, when I arrived the team wasn’t good enough and neither was the squad. There was a need for urgent reconstruction. The ability wasn’t there and the attitude was bad. I oversaw three or four testimonial matches in my first two years and that shows you how old the players were and where their priorities lay. In my six years as a player, only Emlyn Hughes was granted a testimonial. [It was actually four: Steve Heighway, Phil Thompson and Ray Clemence were also granted testimonials.] This was a period where the hunger was always there even though we won the league most seasons. Ronnie Moran was always telling us we weren’t as good as the old teams under Bill Shankly. That motivated us to prove him wrong. I wanted my Liverpool team to be like this.”

Souness recalls the afternoon Liverpool hosted Joe Kinnear’s notorious Wimbledon side and Vinnie Jones scrawled “Bothered” across the famous This Is Anfield sign that hangs over players as they enter the pitch. The reaction inside Liverpool’s dressing room was to laugh it off rather than seek retribution, as they probably would have done a decade earlier. It summed up the attitude.

“We were too soft,” Souness says. “Where were the leaders fighting our corner? In the eighties, we could beat a team by playing football. If the other team wanted a fight, we could beat them by fighting. We could deal with any situation. Things had changed.”

Souness believed he would be the manager that would take Liverpool into the 21st century. He wanted to make his own mark on the club by transforming the way the football staff operated.

“I’d been in Italy and I’d seen how all the big clubs were run there. Since the days of Bill Shankly, Liverpool’s players had always changed at Anfield and got the bus up to Melwood. I recognised it was part of the routine –– the banter in the dressing room and on the bus — but I wanted one base at Melwood, mainly because it would shave an hour off the working day and allow us to focus on other things rather than dodging the traffic in West Derby.

“Anfield was becoming a tourist attraction for out-of-town and foreign supporters and I felt it would be better for the club if they opened up the stadium. They could make more money and also guarantee the safety of supporters milling about in the car park by not having buses going in and out. Anfield would have been used by the players on a match day only. Yet there was great resistance.

“We used to put lager on the bus on a Friday for an away game. It was a particularly strong lager. I was happy for the players to have a drink but I thought it was better if they had a lighter lager. There was also resistance to that. I wanted to change their eating habits. There was great resistance there as well.

“I’d done all this at Glasgow Rangers and because they hadn’t won anything in nine years everybody was buying into it. When you go to a club where there has been non-stop success and go to the players, ‘By the way, you shouldn’t really be eating fish and chips straight after a game,’ it wasn’t easy to convince them.

“It was never going to be an easy transition. It is natural for people to resist change, especially when a method is in place that is tried and trusted. It’s a hard argument. But had the players listened, Liverpool would have been the first club in England to implement it. We’d have been ahead of the game. [Arsène] Wenger came into Arsenal in 1996 when Arsenal hadn’t won a league title in five years and he was able to do it. But, hey, did I try to change things too quickly? Yes.”

Contrary to popular belief, Souness says he did not order the Boot Room to be destroyed.

“That’s a rumour still doing the rounds today but it’s absolute rubbish,” Souness insists. “It was the club’s decision to demolish it. They wanted to expand the press room. The Premier League said the old one was too small, so a decision was made above my head.”

Souness cannot deny he made errors in the transfer market, especially with those he bought. He remains convinced some would have been considered good signings had they been integrated into the team when it was winning rather than struggling for form.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GlUzylxYAYU

“I would say Michael Thomas, Mark Wright, Rob Jones and David James all gave the club good service. You know, I liked committed players. Neil Ruddock, if managed properly, I thought, was a real asset because there were few left-footed centre-backs as powerful as him. He was a better footballer than people remember but he struggled with his weight. I liked Julian Dicks, too. He was aggressive and rugged but wanted to play and had a will to win. I think I made a big mistake in selling Dean Saunders. I should have stuck with him. His goalscoring record was decent. He scored more than 20 in his first season. But I listened too much to players who told me they didn’t like playing with him. I foolishly agreed when I should have stuck to my principles and told them to get on with it.”

When Souness is criticised, the signings of Paul Stewart and Nigel Clough are usually mentioned.

“Both of them came in for big fees, so I can understand it. Paul came in because I wanted us to have a bit more physicality in midfield. It was a department where we were lacking. I’d seen him play as a striker for Manchester City when I was manager of Rangers but he was better at Spurs in the middle of the park. He was man of the match in the 1991 FA Cup final against Forest and was desperate to do well at Liverpool but it never worked out.

“Nigel was very quiet but I thought he’d be able to supply the passes for Rushie. But it didn’t work out between them.”

There was also Danish defender Torben Piechnik and Hungarian midfielder István Kozma, two individuals clearly out of their depth.

“They were relatively cheap signings and both were intended to be squad players. Because of injuries, they had to play more often than I would have liked. Some of these you get right, others you get wrong. Both were low risk. But when the team is losing, players like this get highlighted a lot more.”

Souness had the opportunity to sign other players that could have made a difference. The first was Peter Schmeichel, who as Manchester United’s goalkeeper would win 15 trophies.

“I hadn’t been at Liverpool long. Ron Yeats was the chief scout and he came into my office one day and showed me a letter. It read: I am a Danish goalkeeper who has been a Liverpool supporter all my life. I am willing to pay for my own travel expenses. Can I come to Melwood for a week’s trial? I was trying to edge Bruce [Grobbelaar] out. But it was proving difficult. I thought that if another goalkeeper turned up, we were going to have more problems with Bruce. So it never happened.”

The next was a striker later voted as the greatest player in United’s history.

“We played Auxerre in the UEFA Cup. We lost 2-0 in the first leg in France, then won 3–0 at Anfield. Jan Mølby scored a penalty after about two minutes and that set us on our way. After the game, Michel Platini knocks on my office door and comes in. He said that he had a player for me. ‘A proper player.’ He told me that he was a problem in France but would be perfect for Liverpool. The player was Eric Cantona. I said, ‘Listen, I’m fighting lots of fires here at the moment; I don’t need any more trouble.’ It was another situation where I should have been more open-minded.”

A deal for Alan Shearer was closer.

“I had a conversation with him on the phone while I was sat outside McDonald’s near Stockport railway station. I was really confident of getting him and I told my wife-to-be, Karen, that I really believed we’d push the deal through. Whether it might have been a woman’s intuition I’m not sure, but she told me that he’d go somewhere else. And she was right. When I later became Blackburn’s manager, I spoke to Tony Parkes, who’d worked for the club over a number of years. Tony told me that all the people at Blackburn recognised whoever got Shearer would end up winning the league. They were right too. I later managed Alan at Newcastle and I have to say he was the best English centre- forward in post-war history.”

Souness is more frustrated that he did not get to see young players like Robbie Fowler, Steve McManaman and Jamie Redknapp flourish in the mid-nineties. His problems at work, though, were nothing compared with his problems at home. Souness faced not only a bitter divorce, the death of his father due to natural causes as well as the death of his two German Shepherd dogs who were shot by a farmer herding sheep on a field near his former home in Knutsford, but also the sudden news that he required urgent open-heart surgery, although he swears his health had nothing to do with the pressures of football. “I had two uncles that died of heart attacks in their thirties. I’ve got the dodgy gene.”

A triple-heart bypass operation for a then 38-year-old man would scare most people but he insists he took it all in his stride. “I was determined to be the hospital’s best-ever patient and get back into football as soon as possible, so I pushed myself.” Souness was due to be released but collapsed, resulting in a second operation, and spent 28 days in bed rather than 10.

The ordeal of coping with so much should have worked for him like it did for Gérard Houllier years later but instead it only served to further alienate him from the fans at a time when league results were not in keeping with expectations. He does not blame the stress of the time for the gross misjudgement that followed.

Souness shared a professional working relationship with The Sun’s Merseyside reporter, Mike Ellis, a journalist who eventually wrote his second autobiography in 1999. That Ellis was on holiday during the week beginning Monday, 13 April 1992, Souness says, was significant.

He’d agreed to sell the story of his hospital ordeal to Ellis. After his operation, the interview appeared in The Sun on ‘the 6, 7 or 8 April’. Initially, there was no angry reaction, with Souness claiming Ian Rush and Tommy Smith, both Liverpool legends, had had public dealings with the newspaper before him and post-Hillsborough without a public fallout.

Souness was approached again on 13 April by a photographer from The Sun, asking if he could take a picture for the following day’s edition, a picture that would reflect his road to recovery. Liverpool were playing Portsmouth that evening in an FA Cup semi-final replay at Villa Park. With Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans in charge while he was in hospital, Souness told the photographer that he could take a picture providing Liverpool progressed, as it would be bad if he was seen smiling in his hospital bed the morning after a defeat.

Eventually, Liverpool did win but only on penalties. Because the photograph was taken so late — beyond the 11pm copy deadline — editors decided to use the picture a day later instead and included a short caption. Rather than appearing on 14 April, Souness’s photograph was printed in The Sun on 15 April 1992 — the third anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster.

“Mike would have advised the paper not to print it on that day, there’s no question about it,” Souness says. “Instead, it looked terrible: me smiling and confident of recovery on the same day a lot of people were still in mourning.”

As he was in Scotland at the time of the disaster, Souness maintains he did not appreciate the depth of bad feeling towards the newspaper.

“I have nobody to blame but myself, though,” he adds. “I gave all the proceeds from the interview to Alder Hey Children’s Hospital. I knew I’d got it wrong. Ignorance is no excuse.”

The episode made Souness’s position at Liverpool “impossible”. Merseyside reporters, who had always worked as a pack, were annoyed that they had been left out of an exclusive story and were unsympathetic towards Souness in their column inches when the public tide turned against him. Souness sat on the bench during Liverpool’s FA Cup final victory over Sunderland and looked ill. “What I should have done is resigned after the FA Cup final both because of the mistake I’d made and because of my health. Looking at pictures of myself, I shouldn’t have been there, because I was still fragile.”

Somehow, Souness continued for another 18 months. He even survived a period where Liverpool slumped to 17th in the Premier League table as late as March — just three points above the relegation zone. Though the team finished the 1992–93 season in sixth, in a congested table, it was a mere 10 points above the bottom three.

“I lost the dressing room and that hurt me, because it started with some of the players I’d worked with and looked after as young boys,” he says. “I was disappointed in a lot of people but I was far from blameless. I went into Liverpool probably believing I knew everything there was to know about management because I’d been successful elsewhere. The setback at Spurs served me well for the rest of my playing career but that was 20 years earlier and as a manager it felt like I could win everything in a rush. I’m not blaming anybody but myself, because if I did it again now, I’d do a lot differently. I would hate to think this is coming across as me not holding my hands up.”

To hear this admission from someone who appeared outwardly indestructible as Liverpool’s captain is quite humbling. Souness is seen as a cold and uncaring type of person but he clearly regrets the errors made in his life and the opportunities missed.

Souness realised his time was up at Anfield before Liverpool’s FA Cup replay with Bristol City in January 1994. While he was eating his pre-match snack of toast and tea at the Moat House Hotel, Souness could hear the visiting manager holding a team meeting in the next room.

“Russell Osman had seen enough of us in the first game at Ashton Gate to tell his players that if they matched us for effort we’d bottle it in front of our own supporters. I knew he was right. This was coming from Bristol City in the old Second Division.”

After a 1–0 defeat, Souness tendered his resignation in person to chairman David Moores as well as Peter Robinson and, with that, he was gone.

“The bottom line was I didn’t feel I was getting the full support of the players,” he says. “After The Sun thing, the supporters inside Anfield could have turned on me in a big way. I was aware attendances went down but verbally they were always very encouraging to the team.”

Souness continued his management career and there were some achievements. After winning the Turkish Cup at Galatasaray, he planted the flag of his club’s colours in the centre of the pitch at city rivals Fenerbahçe.

“One of their board members had called me a cripple earlier in the season, so I thought it was the right thing to do,” he reasons. “I loved it in Turkey and would have stayed much longer had the president that appointed me been elected again.”

Abroad, he also managed Torino and Benfica, and at home, Blackburn Rovers (where he was happiest) and Newcastle United. Yet the drive to improve himself and get results meant he could rarely enjoy the moment.

“There have been far better players than me that have won nothing,” he concludes. “I won a hell of a lot. I’ve had the most fantastic career in football when you consider where I started off to where I ended up. I have 26 medals to my name. I’m deemed as a failure as a manager of Liverpool. But I won 11 trophies in three countries after moving on. There are far better managers than me who haven’t won anything. So I’m proud of what I’ve achieved.”

Men In White Suits by Simon Hughes is now available in paperback for £8.99.

Souness, like Kevin Keegan, is a massiveLiverpool legend who doesn’t get invited to Anfield nearly as much as they should.

Kenny, Rush, Hansen and the rest are heroes too and are always at Anfield but I don’t like the way Souness and Keegan don’t get the recognition they deserve among modern fans, and also the people that run Liverpool.

A foreign supporter’s only source of inside knowledge of the days gone by are these type of informative reads. Great stuff, would love to read the book.

Brilliant, absolutely fucking brilliant piece of writing. Thank you.

One man I’d dearly like a pint with.

Nice piece.

Souness the player was the finest midfielder and leader I’ve ever seen in a red shirt. Indeed I’d go further: he was the finest midfielder and captain these islands have produced in my lifetime. But as a manager he was an unmitigated disaster. He’s a winner, so he needs a narrative that explains his failure at Liverpool, I understand and respect that. But the truth is he inherited a team of champions and turned us into a team of chumps. Beardsley, Staunton, McMahon and Houghton had plenty left in the tank, and all the top players wanted to sign for Liverpool: we were the best club in the land. But instead we signed Paul Stewart, Julian Dicks, Dean Saunders and Neil Ruddock: none of these men were fit to wear the shirt. Reading that Schmeichel and Cantona were available only serves to rub salt in the wound. Imagine what we could have achieved had Souness, our greatest captain, one of our greatest players, had an eye for a player?

There were some mitigating circumstances, of course, notably Gary Gillespie’s problems with injuries. He’d have been a worthy successor to Hansen, but all the qualities that made him such a great player seem to have made him a terrible manager. He was stubborn and pig-headed. Had he been less so he might have made a go of it.

Yes, but we should not forget that Souness was a great player and epitomised everything the we fans want to see in a player. It is about time we recognise him for his achievements on the field.

I don’t think his achievements as a player have ever been called into question, have they? There wouldn’t be much argument over whether or not he deserved a place in any Red’s All-Time LFC XI. But like it or not, his blunders and errors of judgement as an LFC manager have tainted his reputation. He got rid of too many players far too quickly and signed some proper shite (as has every LFC manager since, to be fair).

I tell you what, though – I respect him for never having tried to shift the blame onto anyone else. I saw him interviewed by John Inverdale on the BBC years ago, and he admitted without hesitation that he did a lot of things wrong as LFC manager. He took his lumps then as he does here, so I give him full credit for that. It wasn’t his fault that he came to us from a job where he’d been given an open chequebook and carte-blanche to slaughter the two biggest sacred cows in Scottish football. With his record at Rangers, he would have got offers from all over the place. I just wish he’d been given the United job…

Excellent article, highlights the human aspect of this crazy game we all adore. I can’t help but feel sorry for him, a driven personality desperate to succeed, it’s easy to blame Souness but behind the scenes the club has stopped, while Utd were building a bigger ground and pushing marketing we sat and don’t nothing because we’re the best team in Europe, living on old glories.

He got some things wrong, but in a greatest 11 he’d be one of the first.

11 trophies in three countries after leaving Liverpool! Which ones were those Graeme?

Copa Italia, Scottish premier league X 3, Scottish league cup x4, Turkish cup, Turkish super cup, English league cup.

Regards

Graeme

Boom. Class reply

Best midfielder I’ve seen in a red shirt. You saw him lead the team out and you knew we had a chance, no matter who we were playing. It’s a pity he doesn’t get the recognition his towering talent deserves.

Deepest respect for Souness. Natural born leader with winning DNA.

We would win many more games with half a leader like Souness in current team.

Excellent extract, the whole book must be really good.

As a truly magnificent player and inspirational leader it is a shame how the managerial reign has affected his overall standing (The Sun article was a terrible mistake by him). I also find his excuses regarding an ageing squad, whilst having some merit, a bit disrespectful to Kenny (much like Houllier talking down the state of the squad when he replaced Roy).

I hope that sooner rather than later there could be a thaw in ill-feeling towards him, it would be marvellous to see him as a more regular guest at Anfield like some of the other lads.

Isn’t it about time?

I’d love to see a Kenny and Souness sit down on the quality of that inherited squad. I’m sure Kenny would disagree with a lot of that shite.

11 trophies? Says 3 on his Wikipedia.

Great read.

A really good interview with Souness is on Graham Hunters podcast ( there is also a very good one with Peter Beardsley and one with Carragher too)

Well worth a listen:

https://audioboom.com/channel/grahamhunter

Great read, what a player Souness was, we all need a bit of a loon in CM. Think he caught us really at the point the game was moving from one era to the next with diet etc etc.

When a new manager comes in one of the first things they say is that the squad up to much & not fit enough, Klopp said exactly the same thing.

Think you can see the regret in his face with the paper interview, something as he says he’ll always have to live with.

Hi Brian, I thought Klopp never said any negative word about the current squad nor hint any blame on the previous manager.

instead he is always positive, and always rejected about suggestions on “wholesale changes”. He publicly stated that he could work with the existing squad when he reviewed the individuals before accepting the job. and also be mentioned that the current squad quality is much higher than the BD squad when he first took over.

Enjoyed this book very much. The bothered incident with Jones tells you all you need to know about the club at that time.

I and others never understood why he didn’t sign David Batty. There were rumours at the time.

I think Keane was a rumour too. Kenny should have bought Ince from West Ham too.

Someone I know said Batty wasn’t all that really. He saw him play a few times and despite his hard man image, he was actually a mediocre player who sometimes went in too hard. Instead of him, Souness could have signed Gary McAllister who was tipped to join an Italian club in the mid ’90s. Back then, he was still at his peak and I could imagine him mentoring Jamie Redknapp in central midfield with Barnes on the left and McManaman attacking from the right. Under Roy Evans, it would have been awesome if he signed Paul Gascoigne back from Italy. He scored goals galore for Rangers and could have helped Liverpool win the Premier League.

what a player this lad was at middlesbrough tottenham rangers and Liverpool best iv seen on the park he could win you a game in the tunnel he was that good o k he didn’t really cut it as a manager very out spoken a bout the game but what a player

Souness was my hero at Liverpool as a player and i became a Rangers fan too because of him.I always believed that he couldn’t resist going back to Liverpool to be the manager even though he loved it at Rangers and was so successful,and always thought there were too many problems after Dalglish left as there were too many players that didn’t have any fight left to play for our great club,yes as he says he wanted to change things too soon and made other mistakes but I hope that all the Souness haters out there read this and are more understanding towards him after all Dalglish made alot of mistakes too but he is still looked at as a Liverpool Legend.From Andy(Souness Loyal)

Great player , not too good Liverpool manager ..Inherited a great team ..late 20 s to early 30 s is not old by any footballing standards ..However despite certain whinings of players you dont throw out the baby with bathwater ..For some reason Liverpool was never able to recover .Now with hefty pockets and a good manager , I hope we’ve learned our lesson

What a cracking read. Souness was up there with Keegan, Dalglish and Gerrard as one of Liverpool’s greatest players. I never realised he was handed the captaincy after the home defeat to Man City. My family and I were at that game and we were shite. We slumped down to the bottom half of the table. I think Rushy started to get a few more games after that result (too lazy to Google) and we went on a good run and finished Champions.

I agree. Liverpool finished second, behind Arsenal in 1991. After the shock of Kenny resigning after the FA cup match with Everton, Ronnie Moran took over as caretaker manager. Certainly, some players were coming to the end of their careers, but the side wasn’t that bad.