YOU know the story. It’s 1984. It’s the European Cup final. A fearless Liverpool side led by Graeme Souness belts out the Chris Rea song that had become their anthem in the faces of the Roma team they were about to take on in their own backyard. And that’s how the title of TONY EVANS’ book was born. I Don’t Know What It Is But I Love It details the 1983-84 season — a booze-fuelled campaign that ended with the Reds lifting three trophies: the First Division title, the League Cup and the European Cup. Here, we have two extracts from Tony’s book, kicking off with the night that Liverpool’s captain fought back.

YOU know the story. It’s 1984. It’s the European Cup final. A fearless Liverpool side led by Graeme Souness belts out the Chris Rea song that had become their anthem in the faces of the Roma team they were about to take on in their own backyard. And that’s how the title of TONY EVANS’ book was born. I Don’t Know What It Is But I Love It details the 1983-84 season — a booze-fuelled campaign that ended with the Reds lifting three trophies: the First Division title, the League Cup and the European Cup. Here, we have two extracts from Tony’s book, kicking off with the night that Liverpool’s captain fought back.

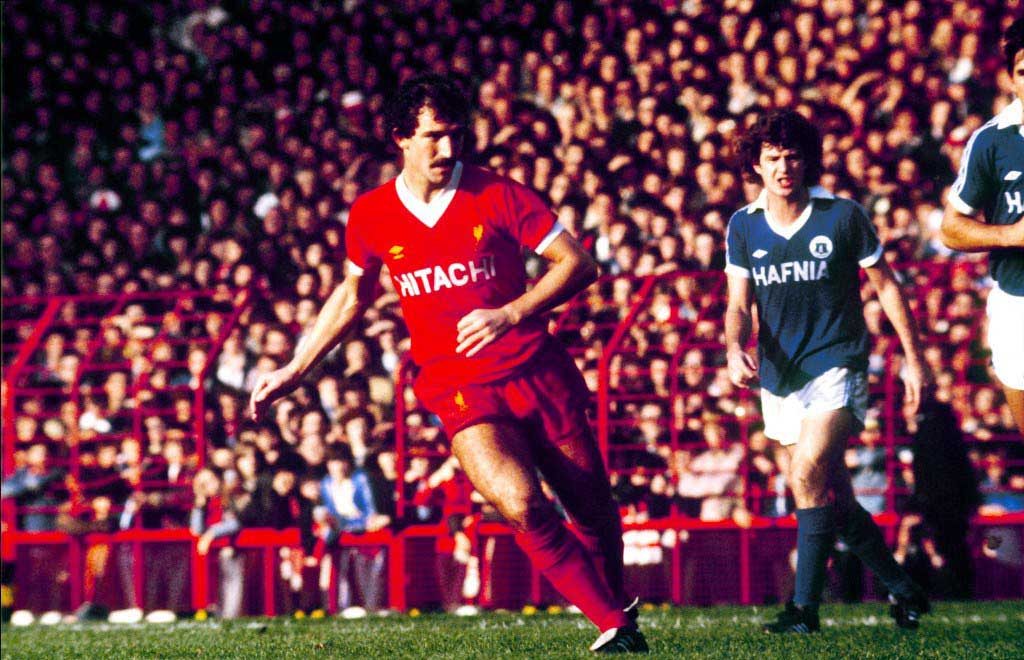

In March 1984, Liverpool were playing the first leg of the European Cup semi-final against Dinamo Bucharest at Anfield. They were leading 1-0 and Graeme Souness became involved in a running battle with Lica Movila, the visiting side’s captain.

As the game ground on to its spiteful conclusion, Souness changed the complexion of the entire tie.

Another attack broke down in front of the Kop and the Dinamo defence rushed forward to catch any lingerers offside while Liverpool dropped back to cover any potential breaks. Left behind on the edge of the area, lying alone, was Movila, clutching his face.

Nearly everyone in the ground had been watching the ball and had not seen what caused the Dinamo captain’s injury. The referee summoned the Romanian trainer and various players milled around. Movila appeared to be suggesting he had been punched.

Souness stood, some distance away, hands on hips, a picture of innocence. Steve Nicol was on the bench and, as a defender still learning his trade, had less focus on the ball than most. He was studying the back four’s movement.

“The ball got cleared and almost everyone followed the ball,” Nicol said. “I was watching the middle and just saw a red blur, an arm swing and the Romanian go down. You couldn’t see it completely clearly but I’d seen enough. There was a punch. It was a beauty.”

The youngster was experienced enough to know exactly who was responsible. “It was a classic Souness moment,” he said. There were still 20 minutes to go. If things had been tense so far Souness — in Cold War terms — had just made them go nuclear.

Movila walked to the sidelines clutching his jaw. It was broken in two places. Souness, who had been so enraged when Kevin Moran had smashed Kenny Dalglish’s cheek, had just pulled a similar stunt. And he was proud of it.

“Movila was the worst of the lot,” he would later say. “He kicked everything that moved and three times caught me with punches off the ball. I went completely crazy when he came in late and high yet again and as he half turned I let loose with the best punch I have delivered in my life.”

“Movila was the worst of the lot,” he would later say. “He kicked everything that moved and three times caught me with punches off the ball. I went completely crazy when he came in late and high yet again and as he half turned I let loose with the best punch I have delivered in my life.”

“I heard it more than I saw it,” Alan Kennedy said. “A thud. I just saw a red blur and heard a boom. He turned into Souness, too, which probably made it worse.” The left back could not believe that Souness had escaped unpunished. “How the ref didn’t see it I’ll never know,” Kennedy said.

Dalglish was yards away from his team-mate when the blow was landed. “Oh, I saw it,” he said. Was it as good a punch as legend has it? “Oh yeah.” The incident had been brewing for some time. “Movila was warned,” Dalglish said. “Graeme told him if he pulled his shirt again he’d get it. He got it.”

Even some of Souness’s team-mates thought that their captain had overstepped the mark. “I’m not saying it was a bit naughty but it was…well, a bit…let’s just say Movila wasn’t happy,” Kennedy said.

No one in the Dinamo camp was. If Souness had not been a marked man before, he was now. In the final minute, he went into a challenge with Gheorghe Multescu. The Romanian did not even try to disguise his kick towards his rival’s groin. This was even before the full scale of Movila’s injury was apparent.

As they left the pitch at the end of the game, Souness passed the injured party. “He was standing at the mouth of the tunnel with a towel around his head and his face packed with ice,” the Scot said. “There were two big fellas, one either side of him. They looked like cops. They were scowling at me.”

The Liverpool captain was not intimidated. “It was all a bit of a laugh,” he said, before adding reflectively, “Well…not for him.”

Kennedy says that Souness was dismissive afterwards. “Listen, whatever he got, he deserved. End of story,” the left back remembers the captain saying. It was, however, far from the end of the story. As Brian Glanville wrote a few days later: “I don’t think I would like to be Graeme Souness in Bucharest.”

Kennedy says that Souness was dismissive afterwards. “Listen, whatever he got, he deserved. End of story,” the left back remembers the captain saying. It was, however, far from the end of the story. As Brian Glanville wrote a few days later: “I don’t think I would like to be Graeme Souness in Bucharest.”

The Liverpool captain, known as Champagne Charlie to his team-mates, had to run the gauntlet in Romania.

“Everyone was waiting for Charlie,” Nicol said. “At the airport, people were screaming at us. It took us a little while to realise it was all about Souness.”

It was a time for pulling together, rallying round the captain. Yet typically, the rest of the squad saw the situation as an opportunity to have a laugh at Champagne Charlie’s expense.

“Once we twigged it was all about him, that was it,” Nicol said. “We got on the coach and we were all pointing at him, directing the angry mob to where he was sitting so they could bang on the window. We were laughing at him and pointing. It went on the whole trip.”

If anyone could cope with the harsh intensity of Bucharest, it was Souness. But his team-mates were relishing his discomfort and keen to keep the pressure up.

“They were banging on the coach,” Souness said. “I was sitting there and this fella came up to the window and his face was level with mine. That must have made him about seven foot tall. He was a giant. He was making gestures like he was gouging out eyes.”

Lesser men might have moved to another seat but the Scot quickly formed a strategy. “I looked around and pointed to Alan Kennedy,” Souness said. “He had a moustache and curly hair and was about my size. He could easily have been mistaken for me if you didn’t know. ‘That’s Souness,’ I said to the giant, shaking my head and directing him to Alan. ‘Not me, him.’”

Lesser men might have moved to another seat but the Scot quickly formed a strategy. “I looked around and pointed to Alan Kennedy,” Souness said. “He had a moustache and curly hair and was about my size. He could easily have been mistaken for me if you didn’t know. ‘That’s Souness,’ I said to the giant, shaking my head and directing him to Alan. ‘Not me, him.’”

The baiting continued throughout the trip. “When we went downstairs in the hotel, there’d be people waiting around and we’d all point at Charlie,” Nicol said. “We were loving it!”

Things got worse in the stadium.

“There were all these daft banners saying what they were going to do to me,” Souness said. “Then Alan Hansen worked out that when the ball came to me in the warm-up they’d boo, so they started passing every ball to me. Every time it arrived at my feet there was a crescendo of noise.”

As the anger turned up a notch, so did the piss-taking. “You could feel the tension rising,” Kennedy said. “We were all going: ‘Oh, Graeme, please, there are 60,000 lunatics here and the police are all against us. They’ll be on the pitch in a minute! Souey, of course, couldn’t give a shit. He was absolutely loving it. Loving it.”

The Romanian side made their intentions clear before the kick-off. “Their captain had played up front at Anfield,” Souness said. “He was of a similar shape and size to me and had curly hair. He was aggressive during the coin-toss and then dropped deep to play in midfield. He pointed to himself and then to me, as if to say, ‘It’s between us now.’”

It was a challenge Champagne Charlie would not let go unanswered. “I gave him the thumbs-up,” he said. Within seconds, the assault on Souness began. “A couple of their players had a pop at him,” Kennedy said. “But he got a couple of them back, too. He was good at doing his little bits and pieces off the ball when he needed to.

It was a challenge Champagne Charlie would not let go unanswered. “I gave him the thumbs-up,” he said. Within seconds, the assault on Souness began. “A couple of their players had a pop at him,” Kennedy said. “But he got a couple of them back, too. He was good at doing his little bits and pieces off the ball when he needed to.

“It was pretty fierce. Every time Graeme got the ball, their whole team were out to get him. But he was just too good for them. They couldn’t close him down.”

On the sort of pitch that was made for fighters and not the flighty, Souness imposed himself. “He rode everything they threw at him,” Dalglish said. “Lesser men would have folded.”

Before the game, Souness’s colleagues were happy to let the captain be singled out. Now they worked hard to take the strain off him. “He understood the pressure and coped with it,” Kennedy said. “He needed his team-mates, though. We made sure he always had an option so he never got caught in possession.”

As usual, Joe Fagan’s plan was to take the crowd out of the game. In such hostile circumstances, it needed more than a spell of possession and judicious fouling. In this maelstrom, it needed something special. Souness and Ian Rush provided it.

A Sammy Lee corner was cleared but dropped only as far as the Liverpool captain some 25 yards out. For once, there was no Romanian nearby to rake his studs down Souness’s leg. The Scot dinked the most delicate ball into the area along the inside-left channel. Its perfect weight and pace made a beautiful counterpoint to the physical ugliness of the game so far. The ball dropped to Rush, who expertly dribbled past the left back and shot instantly from an angle. The wet net rippled and the crowd groaned. With just eleven minutes gone it was 1-0, Liverpool were two up on aggregate and the tie was over.

In the midst of a political crisis in Liverpool, the city’s politicians had to divert their attention to football to stop a diplomatic incident before the League Cup final between Liverpool and Everton

THE League Cup final threw up a massive problem for Liverpool City Council, who already had enough to worry about.

In the local elections of May 1983, the Labour Party won control of the city. The results were very much against the political trends in Britain. The Labour manifesto contained commitments to maintain jobs and build new houses despite Whitehall policy demanding massive cuts to regional budgets.

Labour was elected in a landslide and the councillors were on a collision course with the Thatcher regime. In the spring of 1984 it became clear that the council were determined to carry out their electoral promises. To do that, they would have to spend more than their allocated budget and break the law. The Labour group argued that too much government money had been withdrawn from Liverpool over the previous three years. Both sides took entrenched positions, The Guardian reporting that ‘the air is thick with talk of with talk of rebellion, even revolution’.

And then football interrupted proceedings.

The crucial budget meeting was scheduled for 29 March, accompanied by a city-wide strike. This was four days after the League Cup final. Politicians in the city were embroiled in lengthy and exhausting talks to try to avert the crisis when a bigger problem reared its head and took the focus away from the fiscal meltdown. Negotiations were shelved and more important matters attended to.

“It was the first time the two clubs had played each other at Wembley and the plan was for both teams to go on an open-top bus tour afterwards,” Derek Hatton said. Hatton, an Evertonian, was deputy leader of the council, its most visible face and one of Thatcherite Britain’s public enemies. On Merseyside, he was one of many with twin obsessions.

“Football and politics were everywhere at the time,” he said. “Every pub had an expert who could sort out the city’s treasury and others who could whip the football clubs into shape. Both subjects were important to people.” Shankly’s flawed axiom had it that the sport was more important than a matter of life and death. It is not. But it certainly edged out the politics.

“We were having huge budget battles, London was threatening to suspend the council and send in a commissioner, and the press were screaming for blood,” Hatton continued. “Then we had a real crisis. The question was: who would go first on the open-top buses?

“We thought the winners would take the lead bus and the losers follow on. Then Howard Kendall said to me, ‘If you think we’re going behind those red bastards if we lose, you can fuck off!’ He wasn’t giving an inch.

“So now we had to convince the Liverpool supporters on the council to use their influence at Anfield to stop this blowing up into a serious diplomatic incident. In the middle of the budget battle, with this massive economic turmoil, the most important item on the agenda was football. You wouldn’t want to underestimate the power of the game.”

A compromise was reached. The teams would mingle on the homecoming buses. Negotiations with the government were not fated to be resolved so easily.

Extract from I Don’t Know What It is, But I Love It: Liverpool’s Unforgettable 1983-84 Season, published by Viking Books at £16.99. To order it from The Times Bookshop for £13.99, with free p&p, call 0845 2712134 or visit thetimes.co.uk/bookshop The book is also available in paperback.

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: PA Images

Like The Anfield Wrap on Facebook

Subscribe to TAW Player: https://www.theanfieldwrap.com/player/subscribe

I was just behind the mop goal that night and seen the infamous punch and what a punch it was it came from nowhere and wiped the lad out in a flash , they had been up to all kinds of tricks that night and Souy had had enough

Souey, you hero. Any chance someone could invent a time machine and we could stick the 1984 vintage Souness in our midfield come August?

If we had a vintage Souey in our team Rodger’s would either play him at right back or we’d sell him.

All this history and talk of past glories is just making the decline we are now in even more depressing. Last season we had top 4 ambitions. This season, we might get 5th and a cup if we are lucky. Fuck FSG and Fuck Bodgers. No wonder sponsors slip away on the quiet.