THE tragic story of the Heysel Stadium disaster is a tale which pains any decent Liverpool fan. I flew to Brussels on a charter flight from Speke airport with my dad and his two friends on the morning of May 29th, 1985. I had to employ my keenest negotiating skills to be allowed to travel in the first place; the match between Liverpool and Italy’s favourite and most glamorous club, Juventus landing two days before the start of my A-Levels. The chance to see Liverpool in a European Cup Final for the first time meant the exams which potentially shaped my future played second fiddle to the Reds’ quest to clinch a fifth continental crown and lay claim to the trophy for keeps.

THE tragic story of the Heysel Stadium disaster is a tale which pains any decent Liverpool fan. I flew to Brussels on a charter flight from Speke airport with my dad and his two friends on the morning of May 29th, 1985. I had to employ my keenest negotiating skills to be allowed to travel in the first place; the match between Liverpool and Italy’s favourite and most glamorous club, Juventus landing two days before the start of my A-Levels. The chance to see Liverpool in a European Cup Final for the first time meant the exams which potentially shaped my future played second fiddle to the Reds’ quest to clinch a fifth continental crown and lay claim to the trophy for keeps.

My recollections of an era-changing day are formed not so much in moving pictures; instead a series of still, yet vivid images that are forever etched in my mind.

I remember the faces of men on the train to the ground who clearly were not Liverpool supporters — some dressed in England rugby and football shirts and perplexed by the words of Poor Scouser Tommy. I’m haunted by the pleading eyes of a frenzied Juventus fan approaching us outside the stadium imploring us not to go inside where he explained many people lay dead. I cringe now at my unkind sneer and dismissal of him as an excitable, hysterical “Eyetie” as we mockingly ignored his claim and made our way to the turnstiles.

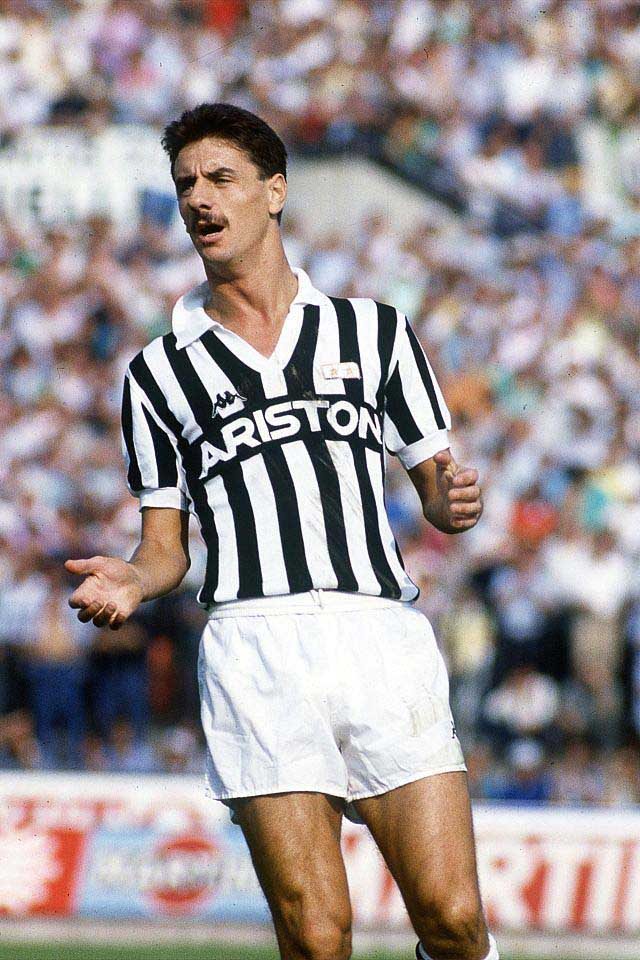

Inside the ground, from our seats along the touchline, the crumbling old relic of a stadium was awash with colour. Gaining admission without having to show our tickets was unusual of course, but was soon forgotten. I still picture the seething, swaying Juventus end, illuminated by brilliant sunshine, adorned with the most magnificent black and white flags and banners — the epitome of my fascination with European fan culture.

I remember feeling keyed up that the atmosphere seemed tense and aggressive and picture some of Juve’s tifosi advancing from their terrace towards the Liverpool end. We backed away from our seats at the front to escape a barrage of missiles thrown from the perimeter track. I can still see my dad’s distressed and angry face pulling down an Italian flag which hung over the front of the stand above as more missiles objects rained into our section.

I shiver a little seeing the dart which flew from the Juventus supporters in the upper tier and struck my dad on shoulder. I remember our escape from the stand, traipsing over hundreds of confiscated flagpoles outside and our re-entry to the stadium via a hole in the wall to the safe haven of the Liverpool terrace behind the goal. Knowing nothing of what had happened earlier that evening we felt we were the victims.

I summon up a memory of darkness falling; a surreal, flat atmosphere and a sense that something was wrong. I remember very little of a colourless game of football and a 1-0 defeat. Nothing else.

I summon up a memory of darkness falling; a surreal, flat atmosphere and a sense that something was wrong. I remember very little of a colourless game of football and a 1-0 defeat. Nothing else.

Next, I recall the shock of the seeing headlines on the Daily Mirror newsstands back at Speke airport and the verbal abuse we received from police officers sent there to greet us. Thirty-nine people, fellow football supporters, followers of our opponents Juventus, had died at that match last night and I knew nothing about it. I immediately thought of the distraught Italian outside the ground who had been right all along.

I can remember nothing of the next three days, which I presume were filled with those exams I was meant to be studying for. I don’t recall any tears in the immediate aftermath, but that changed a few days later when I picked up the Sunday People and read the headline, “We led Soccer Death Charge”, attributed to two Liverpool followers wearing the same bobble hat I wore at the Heysel Stadium.

I cried for the reputation of my team, my City, and myself. If there was guilt it was because I found it hard to identify with or grieve for strangers from a far foreign land who lay dead, although if roles were reversed it could easily have been us. In years to come we would learn the extent of pain for ourselves that comes with the loss of life over something as trivial as football.

It sounds callous but life goes on.

In the summer of 1985 life carried on for me, it continued for Liverpool FC and a year later we were celebrating winning the Double with Kenny at Wembley. The club was rightly punished so there were no excursions to the continent for me and my peers and no European football for six years.

In the time Liverpool spent banned from UEFA competition, the club’s fortunes dipped markedly and it wasn’t until a renaissance inspired by Gerard Houllier that Liverpool returned to compete for the former European Cup in the newly-named Champions League of 2001.

In the time Liverpool spent banned from UEFA competition, the club’s fortunes dipped markedly and it wasn’t until a renaissance inspired by Gerard Houllier that Liverpool returned to compete for the former European Cup in the newly-named Champions League of 2001.

An absence of 16 years had left a lot of time to dream. Robbed of the chance to enjoy a meaningful European Cup final back in Brussels and starved ever since of European reverie to compare with veterans of Inter Milan, St Etienne and the legendary trips to Paris and Rome, the competition became an obsession for me.

Houllier’s underrated team gave us a renewed feel for European glory with the UEFA Cup triumph in Dortmund and followed it with an authentic, exciting assault on the elite tournament a year later before quarter-final heartbreak in Leverkusen signalled the beginning of the end for the Frenchman.

When Rafa Benitez’s debut Liverpool season saw Liverpool edge through the group stages in dramatic fashion with that last-gasp victory over Olympiakos, those European fantasies became more vivid. In my slumber I imagined us parading “Old Big Ears”, but as with all dreams there was something peculiar — we were wearing the hideous yellow 04-05 away shirt. However, such fancy was tempered by harsh reality. Another meeting with Bayer Leverkusen in the last 16 appeared a difficult hurdle but it was an obstacle cleared in surprising and spectacular fashion with a 6-2 aggregate victory.

When the draw for the quarter-finals paired Liverpool with Juventus, naturally the memories and emotions carried forward from that fateful day in May 1985 came flooding back.

The prospect of that perfect colour contrast of the all red of Liverpool opposing the black and white stripes of the Bianconeri was enough to enough to stir the passions, not to mention the possibility of a last four clash with Chelsea. But most of all, a chance to renew acquaintance and offer the hand of friendship on and off the football pitch 20 years on from Heysel seemed the ideal way to at least some of the wounds inflicted on Liverpool’s reputation.

Reality suggested that this was where the Reds’ European adventure would meet its end. This was a Juventus team, managed by Fabio Capello, decorated with diverse talents of the world’s most expensive goalkeeper Gianluigi Buffon, cultured stoppers Lillian Thuram and Fabio Cannavaro, midfield guile of Pavel Nedved, the scheming Alessandro Del Piero and robust attacking focal point, Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

Reality suggested that this was where the Reds’ European adventure would meet its end. This was a Juventus team, managed by Fabio Capello, decorated with diverse talents of the world’s most expensive goalkeeper Gianluigi Buffon, cultured stoppers Lillian Thuram and Fabio Cannavaro, midfield guile of Pavel Nedved, the scheming Alessandro Del Piero and robust attacking focal point, Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

Juve’s galaxy of European stars would face an inconsistent Liverpool side — shorn of the injured Jerzy Dudek, Dietmar Hamann, Xabi Alonso and Djibril Cisse — forced to include novice goalkeeper, Scott Carson, the midfield enigma, Igor Biscan and the unfulfilled talent of French outcast, Anthony Le Tallec.

The calibre of opposition — a quantum leap in terms of quality from group stage adversaries Olympiakos, Deportivo La Coruna and AS Monaco — made Juventus overwhelming favourites to advance, with only Benitez’s renowned organisational and tactical nous and the raucous backing of the Kop to Liverpool’s advantage. Real anticipation at the prospect of some of the best players on the continent gracing the Anfield turf was tempered by a genuine fear that the Reds could be on the end of a damaging defeat that would render the return leg in Italy academic.

Regardless of the result, of paramount importance was that, as a collective, Liverpool supporters could communicate a message of regret, of apology and of friendship to our visitors from Turin. This was no time to be absolved from blame — after all, 14 fans had served prisons sentences for involuntary manslaughter — but instead to acknowledge the actions of some of our followers at Heysel.

In short, it was about building bridges through the shared language of football and saying sorry. In the afternoon of the match, a fans’ friendly arranged at the Academy in Kirkby gave supporters the chance to meet face to face over a game of football, and publicise well-meaning intentions for an evening that offered an opportunity for rapprochement, but such sensitive circumstances could still end with rancour.

The atmosphere at the ground was edgy. On the pitch Liverpool supporters paraded a black and white banner bearing the conciliatory message “Memoria e Amicizia” and the names of the Heysel victims.

Such detail was a painful reminder for both sets of supporters. Ian Rush, whose transfer to Juventus was thought to be an olive branch offered by Liverpool FC to the Turin club, and former Juve man. Michel Platini met in the centre circle carrying a plaque which echoed the message of memory and friendship between the clubs.

Such detail was a painful reminder for both sets of supporters. Ian Rush, whose transfer to Juventus was thought to be an olive branch offered by Liverpool FC to the Turin club, and former Juve man. Michel Platini met in the centre circle carrying a plaque which echoed the message of memory and friendship between the clubs.

As the teams appeared, a particularly resonant renewal of You’ll Never Walk Alone filled the spring air, before giving way to a minute’s silence in memory of the Juventus supporters who perished 20 years previously. The Kop displayed a mosaic projecting the word Amicizia as the promise of an enthralling football match momentarily took a back seat.

Sadly, though understandably, the most fervent contingent of Juventus Ultras who gathered at the front of the Anfield Road stand turned their backs on the ceremony, some shouting and making obscene gestures to cut the silence short. The Kop’s attempt at reconciliation, shunned by significant Juventus minority, saw sentiments of regret and remembrance quickly traded for a visceral, tribal roar.

The decibels on an already electric night were elevated to a new plane amid acceptance that in football as in life, some wounds are difficult to mend. Unlike at Heysel, at least there was meaningful sporting contest to delve into while the festering sores of the past remained largely unhealed.

Buoyed by a seething crowd, Liverpool’s makeshift line-up tore into Juventus from the off. In the opening seconds a slip by the Brazilian, Emerson gifted possession to Milan Baros whose shot was deflected for a corner. Although the corner amounted to nothing, the Reds were quickly into their stride as fans stood on all four sides of the ground during the initial exchanges.

With Baros as the spearhead, Le Tallec in behind; Steven Gerrard and Biscan in the centre and wingers Luis Garcia and John Arne Riise harrying opponents in unison, Juventus constantly ceded possession throughout a frantic 10 minutes to the mocking jeers of the Anfield throng.

If the current squad want a blueprint for the ethos espoused by current boss, Brendan Rodgers it would serve them well to sit down and marvel at the warp speed of the pressing deployed during the opening phase of this game. Normally unflappable technicians; Cannavro, Mauro Camoranesi, Nedved and Del Piero were reduced to jibbering wrecks as a rabid crowd fed off Liverpool’s energy.

In the 10th minute, Steve Finnan advancing from full-back, dispossessed Del Piero and set the marauding Baros away into the right channel to win another corner. Gerrard’s outswinger was expertly flicked across Buffon’s goal by Luis Garcia into the path of an unmarked Sami Hyypia who showed the precision of a striker in netting with an exquisitely controlled left-foot volley from six yards.

As The Fields of Anfield Road and the signature anthem of this European odyssey Ring of Fire were hollered from the stands, Juve continued to struggle in possession in the face of Liverpool’s onslaught. The habitually serene Thuram, with time to dwell, wellied high into the Main Stand and Camoranesi blazed a cross-field ball to no-one in particular into the patrons of the Centenary Stand.

Jamie Carragher and Sami Hyypia, defending on the front foot were snuffing out any of the Serie A Leaders’ counterthrusts before they saw the whites of the 19-year Carson’s eyes in the Kop goal.

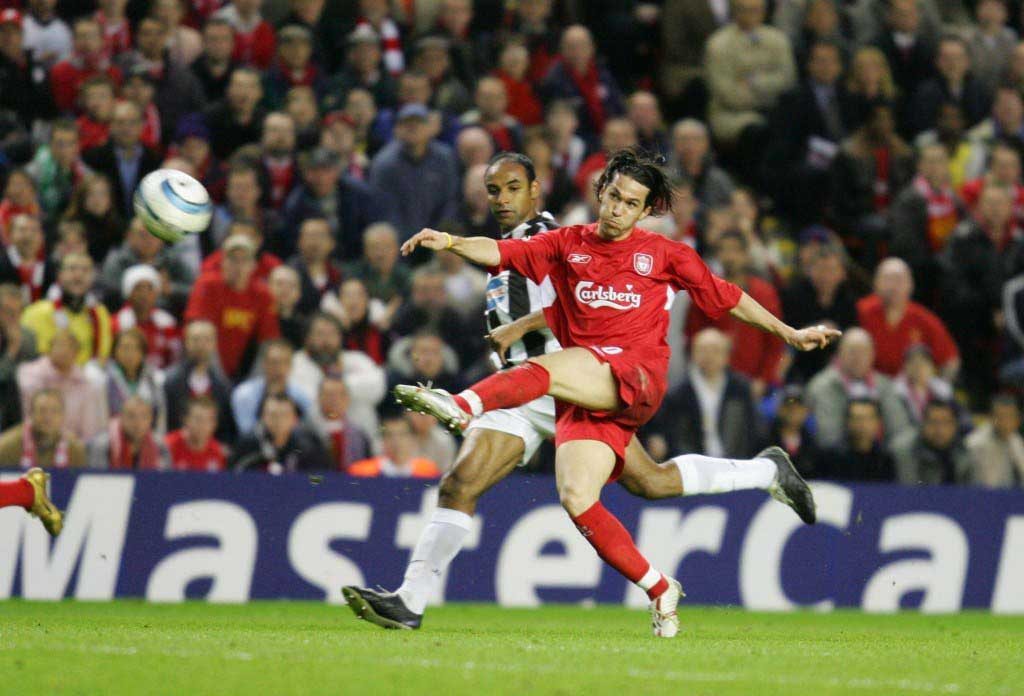

Liverpool continued to press and nearly doubled their lead in 20th minute when Baros’s outstretched leg just failed to connect with Garcia’s inswinging cross. After a wasteful start, the inventive Garcia’s influence was growing and on 25 minutes he produced a shred of brilliance that in the swing of a left boot had Kopites rubbing their eyes in disbelief. If there was a single moment in this campaign that changed Liverpool’s mentality from hope to expectation, this was it.

A neat interchange between Finnan, Biscan and Le Tallec saw the French teenager’s lobbed pass — intended for the run of Baros — seized upon by the petite Spaniard. As the ball bounced, with Buffon marginally off his line, Garcia battered an arcing 30-yard screamer beyond the flailing arms of the immaculately groomed keeper into the roof of the net. “What a goal. What a night!” screamed Clive Tyldesley on ITV’s live feed.

Anfield was in tumult as Garcia peeled away in trademark thumb-sucking fashion, as if celebrating Liverpool’s European rebirth.

Anfield was in tumult as Garcia peeled away in trademark thumb-sucking fashion, as if celebrating Liverpool’s European rebirth.

If the traditional, cautious Italian mindset had kept them circumspect at 1-0, a two-goal deficit forced the wounded animal from its lair. Almost immediately the Reds rode their luck when Nedved gathered Del Piero’s nodded lay-off and squared into the path of Ibrahimovic. The Swede’s well-struck left-foot curled beyond the dive of Carson and smacked against the base of the right-hand post. The crisp sound of the ball cannoning back off the frame of the upright was enough to induce a twitch, if not a minor seizure, among those watching from behind the goal. The curse of the dreaded away goal was thwarted for the time being.

Liverpool responded and nearly added a scarcely credible third when Baros, again running in behind on the Juventus left, rolled the challenge of Cannavaro only for a last ditch challenge to deflect his effort over the crossbar. Capello watched on from the visitors’ bench arms folded in apparent disgust at his team’s inability to cope with the home side’s verve and aggression. Inevitably, the array of attacking talent in the Italian ranks began to make inroads and Del Piero, fed by Nedved’s astute, defence-splitting wall pass, bore down on Carson’s goal only for the tyro goalkeeper to save heroically; a strong right hand repelling the Italian’s precise shot. The Kop erupted in rapturous, relieved applause.

As half-time approached, Turkish Gods intervened when, from a long Camoranesi ball, a well-timed run by Del Piero allowed him to head the ball home only to see his goal incorrectly disallowed for offside. Liverpool’s precious two-goal cushion was preserved at the break.

Years of conditioning to expect the worse carried a sense that Juventus couldn’t be so easily tamed for ninety minutes and so it proved during a nervous second-half. Throughout, the thunderous backing from the home supporters was relentless. If Liverpool were unable to replicate the energetic domination of the opening period, it wasn’t exclusively a rearguard action as the Reds, inspired by the Gerrard’s ubiquitous prompting and the tireless, purposeful forays of Baros, probed for a third while holding their hosts at arms’ length. Jamie Carragher and Hyypia reigned supreme over the subtleties of Del Piero, who was traded by Capello just before the hour for the pace and directness of David Trezeguet.

From our vantage point half way up this vibrant Kop, applauding every headed clearance, every tackle, every block was a weird kind of catharsis; soothing the understandable nerves, but in the most selfish sense imaginable, realising the Liverpool v Juventus European Cup final experience that was denied 20 years previously.

Whatever the right and wrongs, this mattered. It was impossible to erase the shame of what happened that night in Belgium but it never stopped me loving who we were and what we do best. On the pitch and in the stands this Liverpool performance was the epitome of what we stood for before Heysel.

Whatever the right and wrongs, this mattered. It was impossible to erase the shame of what happened that night in Belgium but it never stopped me loving who we were and what we do best. On the pitch and in the stands this Liverpool performance was the epitome of what we stood for before Heysel.

Juventus scored. From a half-cleared corner, the hitherto secure Carson spilled Cannavaro’s downward header from Zambrotta’s cross and the for the first time since the acrimony of the minute’s silence, the Juve Ultras are the most vocal in this Anfield citadel. The depression of the away goal leaves me crestfallen.

Then, I realise that with 25 minutes left, all I want is the win. I want us to beat them. This isn’t a two-leg affair. It’s the European Cup final. It’s my European Cup Final. It’s Liverpool 2 Juventus 1. Evidently, the rest of the Kop feel the same as unabated noise cascades down in support while Liverpool clings to this lead.

My heart misses a beat as Camoranesi lashes a shot just wide from 25 yards. While my voice urges and my emotions rage, Benitez, the ice-man, substitutes the magnificent Baros for Antonio Nunez and young Le Tallec for Vladimir Smicer. As the clock ticks down, Juventus run out of ideas and it is the unheralded Biscan, Djimi Traore, Riise, and Smicer who probe on Liverpool’s behalf while Juventus hold on.

Still, the last few minutes feel like an eternity. I’m desperate for us to see this out. I listen, but don’t join in with a closing, plaintive rendition of You’ll Never Walk Alone. The final whistle blows. Liverpool have beaten Juventus by two goals to one.

The euphoria is fleeting. Suddenly, I feel sombre again. It takes me back; and once more I see the Belgian sunshine and the face of that distressed Italian man in Brussels.

To the victims of Heysel, R.I.P.

LISTEN: Podcast – Heysel 30 Years

READ: Heysel 30 Years: The Barbarians are Coming

READ: Heysel 30 Years: When In Rome

READ: Heysel 30 Years: Why Did No-One See It Coming?

READ: Heysel 30 Years: An Eyewitness Account Of May 29, 1985 In Brussels

READ: Heysel 30 Years: Oh God, What Have We Done?

READ: Heysel 30 Years: The Italian View

READ: Heysel 30 Years: What About Justice For The 39?