AT first, it seemed like a joke. The name sounded funny: Purple Aki. It was Spring Heeled Jack for the 1980s. Just another terrifying urban legend that spread through fear and mass hysteria.

The whole thing appeared preposterous. My younger brothers — five and ten years my junior — were athletes and came home from school and training with tales of this modern folk devil. He was unnaturally tall and unnaturally black — “so black he looks purple” — and he stalked young boys. Then came the comedy payoff: he asked to feel their muscles.

At 22, it was about the funniest thing I’d ever heard. It reminded me of the racist rumour from the 1970s schooldays that the kids from Paddington Comp had broken out of classes and were rampaging around the city slashing the faces of children in other schools. Unpleasant legends with ugly racial undertones cropped up now and again in those days and this had to be another.

And then I met him.

I was working in a warehouse in Canning Place, across the road from the Albert Dock. It was heavy manual work, humping sacks of Littlewood’s catalogues into cages and then out again into 40-foot lorries. One afternoon, I was going up the stairs from the loading bay when I heard a voice behind me. “Do you do weights?”

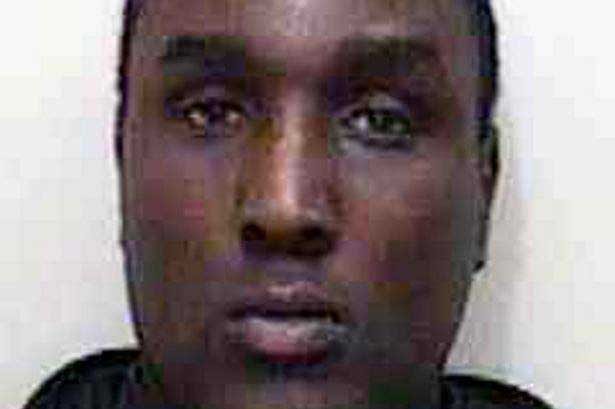

There he was behind me. Akinwale Arobieke. Taller than a tall man. Black but not purple. The bogeyman materialised. “I’ll bet you’ve got big biceps.” He reached out towards me.

“And I’ll throw you down the fucking stairs!”

Front page of the Echo. #AkiWatch cc. @dc_heth @quevega pic.twitter.com/vu6C2uCQYR

— @lordlard (@LordLard) February 3, 2014

He seemed unfazed by the violent reaction and disappeared out the stairwell door. There was nothing aggressive about him. The devil had materialised and he spoke softly.

Over the next year you’d see a lot of Aki. There were a dozen companies in the seven-floor tower block we worked underneath but nobody could work out which one he was connected with. He never spoke to me again but he was around and everyone who worked there was wary, though the lorry drivers from outside the city knew nothing about him. There was much hilarity among the warehouse lads when he asked a runtish wagon driver from Wigan for a feel and was granted a squeeze of a quad. Aki had bagged himself a wool. What could be funnier?

Except it wasn’t always so funny.

On one baking July afternoon a group of us were standing on the loading bay having a laugh and wasting time before the pubs opened again. Aki suddenly came tearing down the pavement opposite, on the other side of the 14-foot spiked fence that enclosed the loading area. At the end of the fence, he stopped, look back towards the Holiday Inn and then began to climb. He scaled the railings with amazing dexterity and the small group of us looked on in awe. As he reached the top and began to negotiate the jagged points, we saw why.

A dozen troll-like Southenders, bare chested and clutching pickaxe handles, were in pursuit. They looked up, Aki looked down. Our side of the fence was five-feet deeper than the pavement where he’d begun his climb. He decided the lesser evil was a 20-foot drop and leapt down, leaving the Southenders smashing their weapons against the fence in frustration. Aki hit the floor hard. At first, it looked like he was injured.

He limped to the steps to the loading bay, while the Dingle hit squad bayed for us to stop him. Then Aki recovered his speed and disappeared into the stairwell where I’d first seen him.

The more you heard about Aki, the less funny it all was. Teenage boys lived in a state of fear. A 16-year-old, Gary Kelly, was electrocuted at New Brighton station in 1986 after an incident involving Arobieke. Aki was convicted of manslaughter but the judgment was overturned on appeal. Fifteen years later he was jailed for a series of indecent assaults on boys. More jail sentences have followed and, over the years, Arobieke has ranged wider across Lancashire, spreading his malign presence into new generations and regions.

What must it be like to be this deeply disturbed man? How many people are living bogeymen? Parents evoke his name to scare the children: “If you don’t behave Purple Aki will get you,” is a common refrain. Banners with his name on are flown at Glastonbury and Youtube cartoons lampoon him.

He was — and still is — talked about like a figment of the imagination, like a character in a horror film. The grim reality is he is not a metaphysical hobgoblin. Akinwale Arobieke is a 53-year-old adult with mental problems and sexual compulsions who has been failed by the justice and medical systems almost as much as his victims.

Aki started as a shadowy figure who walked a fine line between myth and reality. Now it is very different. There’s been a change in tone over the past few years in the age of the mobile-phone camera and social media. The stalker is stalked himself. Passers-by take sly pictures of him and post them on Twitter. He no longer has to ask for bodily contact: young men pose for photos with Aki, the bogeyman’s arms draped around their shoulders and then display the results with pride on Facebook.

A gruesome celebrity is building around this man. It’s at the most minor stage but its emergence leaves a sour taste. The myth of the man in the 1980s was bad enough. The growing cult surrounding him is far worse. It’s easier to have respect for murderous, topless Southenders than the freak-show Aki acolytes.

Purple Aki used to scare people. Now he amuses them. That may well be the most frightening thing about three decades of the Aki phenomena.

It was better when he was terrifying.

I got to know him pretty well about 5 years ago. The first time I met him is one of those stories like we all have and probably tell too often. He was about 15 metres away from me pounding towards me at speed looking seriously angry and shouting ‘is this him’. I was kind of concerned that he appeared to heading for me but thought I must be mistaken. Anyway, he was getting closer and angrier till he was almost on top of me and I thought ‘my god, this guy’s gonna pulverise me. I said, e-aargh mate what’s up and he laughed and said ‘nothing mate, only joking’ and all the lads burst out laughing. Basically, a mutual friend had asked him to do it for a laugh to see my reaction. I saw the funny side too.

Anyway, I got to know him fairly well over the next few months and I couldn’t believe how we was. The person didn’t match the stories. I found him very clever and articulate. Has an excellent knowledge of the law and actually very gentle. One of those who’ll do anything to help you and I did ask him to do something for me and he gave up a lot of his time try and get the answers. Obviously, he’s still a sex offender and they come in all guises so I shouldn’t be surprised.

Just one more thing, we had a party recently, for my daughters 16th and the kids were all talking about him. One said he’d had his muscles felt by him on the train but I wouldn’t know if there’s any truth in it. I was just surprised that even in Chester the kids of today all tell stories of Aki. Facebook hasn’t helped him.

Ha! There’s a Candyman remake to be made the way you’re going on with yourself, Tony.

Glimpsed him walking down Dale Street a few months ago. That’s literally it. That’s my Aki anecdote. Bit sparse compared to yours really…

As being originally a Southender ‘Dingle’ lad myself Purple Aki was spoke about a lot during the early nineties he became my generations Candy Man. In schools there was always someone who had apparently been felt up by him, there was even rumors he used to carve his initials into the backsides of victims. I bumped into him once he was stood outside the shop near our street and he was a monster of a man so to any young lad he would scare them senseless. Myth and Truth can become mixed up but the truth of the matter is and was he was a sexual predator and a potential danger to the public.

Nothing to report eh? And to think I came here to read football.

A little bizarre. Perhaps we’ll get top tips on local supermarket deals tomorrow? :P

Have a look on the site, you’ll be alright.

‘Pop or slash’ !

Is this football or culture? Tough one. Is he preparing to release a derivative, dreary folk song, or is he working on a line of LFC-themed raincoats?

Blimey, this brings back memories…..with going to the all boys Blue Coat school in the 80’s, “rumours” were rife. A mate reckoned he’s been touched up on a bus in town. Another said he was behind us (for a laff) but had us all legging it down Smithdown Road.

By co-incidence my wife was working in the warehouses in the late 80’s and she reckons she knew all the warehouse lads. Hopefully not to well Tony :-)

So after all the pisstakes and moaning about this character, whom I’ve never heard of, I did a google-dance. Very surprised to see “Some results may have been removed under data protection law in Europe” appear.

What next, Crouchy is the Slenderman and behind Marble Hornets?

Ignore the crap, Tony. It’s nice to have a diversion from the shit on the pitch and a manager that appears to have lost the plot.

used to hear the “slash or bash” thing about this fella all the time!!! Thought it was a wind up!

Put bbc iplayer on if your interested. Short documentary aired last night about him. The man who squeezes muscles , searching for purple aki.