SOME people have never recovered from June 2010. Barely a year since Liverpool’s most ferocious title challenge in years, five years since Istanbul, six years since a period which brought us trophies, belief and Luis Garcia – it was over.

At the stroke of a private equity firm manager’s Mont Blanc/Parker, Rafa Benitez was gone. Some were relieved, convinced a double La Liga winner with a Champions League to his name was holding back a team of would-be champions.

A fair majority were dazed, if not wholly surprised, perhaps attempting to rationalise the unrationalisable. There might have been at least a degree of consistency, we thought, in the club’s apparent interest in the avowedly attack-minded Manuel Pellegrini. A smaller, but probably more sane, number simply packed it all in.

A friend – let’s call him Adam, seeing as Neil Atkinson did here – knew exactly how he planned to spend the summer of 2009, had we won the league that year. Sitting in trees, smiling at passers-by and probably singing about Albert Riera. Liverpool sacking Benitez meant that dream had died for ever. You see, Christian. Domino effect.

For Adam, and countless others with more or less ambitious foliage-based plans, there wasn’t much point any more.

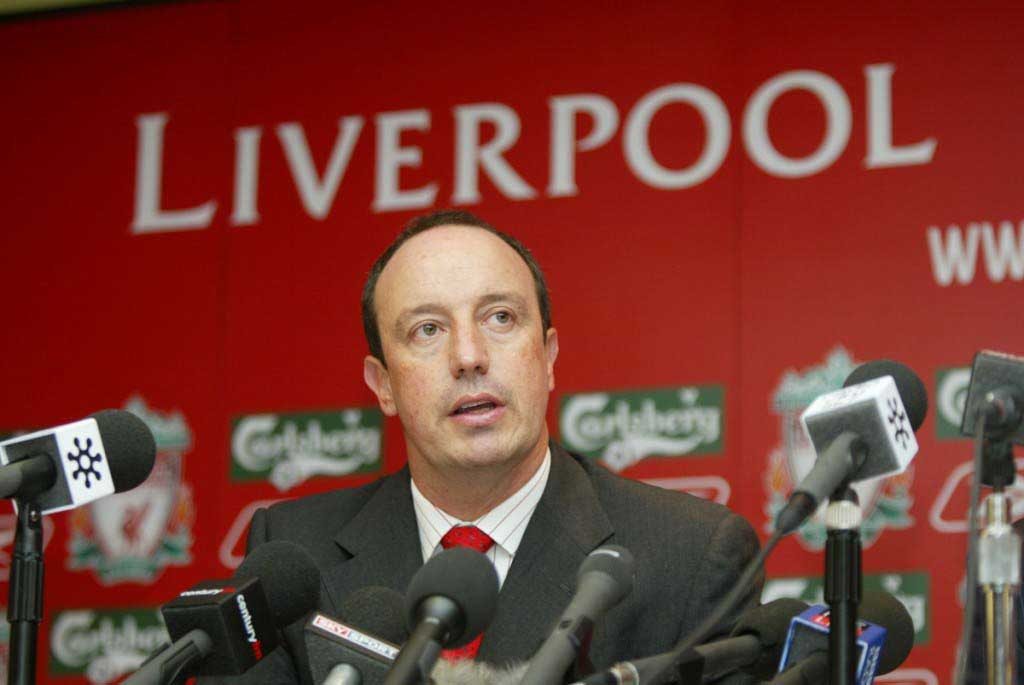

JUNE 2004: Rafa Benitez holds his first press conference as Liverpool manager. He was sacked six years later. Pic: Dave Rawcliffe/Propaganda

Perhaps they might have come round, given time, but in replacing one of Europe’s most decorated and passionate managers with a man with almost literally nothing to recommend him (this is before he got the big watch), the club sealed the disaffection deal.

Regardless of how you responded to the departure of Benitez, what’s undeniable is the mark he left on our psyche. Through a systematic overhaul of almost everything about the side and a recasting of the club as an entity once more to be clung to passionately by its supporters, disliked and feared by others, those six years conditioned us. Inevitably they coloured our perception of the game, its rhythms and requirements.

Key tenets of the Benitez era became articles of faith, in defiance of pundits who would lazily point to zonal marking as the cause of every loss. Never has a manager been more closely identified with his side’s failings – while David Moyes appears perpetually to be let down by his players, sections of the media were in no doubt we were being let down by Benitez.

Squad rotation, pressing, marking zones. A keeper who comes out and claims things. All central to Liverpool during that period, all absolutely consistent with the philosophy imposed by a brilliant manager intent on squeezing everything from the resources available. Intent on winning.

The hangover from 2010 has been difficult to shake. The absence of tangible progress, or at least progress we can all agree on, has left us an oddly fractured body of supporters. The high points under Dalglish – and they were high – and encouraging performances as Brendan Rodgers grew in to last season have not been the stuff of changed perceptions. A fundamental shift in belief systems needs a central cause. Something like a title challenge.

Suddenly, a bit improbably (though not that improbably, if you think about it), we’ve got one. You might be among those who don’t want to believe it, but Liverpool are live contenders for the Premier League. But how? Brendan Rodgers doesn’t rotate on anything like the same scale as Benitez (or, for that matter, Alex Ferguson). His teams do tend to press, but can also sit off opponents and build a lightning counter-attack from deep. And his goalkeeper stays on his line.

Oh, how Mignolet stays on his line. Gloriously, magnificently rooted. Very occasionally he will venture out, look unsure, get back to the line, probably save something in a minute. And it’s fine. Honest.

JOB DONE: Brendan Rodgers congratulates Simon Mignolet after the win at Fulham. Pic: Dave Rawcliffe/Propaganda

In A Life too Short, Robert Reng tells of how Robert Enke spent months at Benfica adjusting to taking six or seven steps forward. On signing for Barcelona, he was told to come out further still. Barca signed a brilliant shot-stopper, the archetypal German goalkeeper, and tried to make him a ball-player.

He was, in his own words, “not Maradona.” In being as close to the German model as Liverpool have had for years, Simon Mignolet is naturally inclined not to come out. He is also, quite clearly, being instructed to follow those natural inclinations. This may not always be the best way to deal with a given situation, but neither is coming out every time. Mignolet consistently stays. Everyone in the squad should know this and make their own decisions accordingly.

The other key aspect of Liverpool 04-10 was the pursuit of control. Possession-based 2-0 wins with 30 minutes to spare were the order of the day. Some league games were grist to the mill, part of a wider plan to wear down challengers. Rafa Benitez had won leagues. He knew how this was done. Brendan Rodgers hasn’t won leagues, but he’s won a lot of football matches by big scores, often by surrendering low-quality possession to sides who don’t necessarily want or expect it. It’s a different approach, but a valid one. It’s worked. And for all the emphasis on control and calm, the games we treasured most from the Benitez era, the games where we looked like champions in waiting, involved four and threes and late winners all over the place.

These are the games which expose the flaws in statistics as an absolute marker in football.

They don’t care if nobody’s ever gone from 7th to 1st in a single leap, or what your points per game against teams in 7th to 11th are. Because they’re not sentient beings, they’re football matches.

Lots of good work is done by talented people who look at what the data can tell us. This happens inside the club, and among fans who often pick out trends which point the way towards future results extremely accurately. But right now, they feel flimsy at best. We’re doing things differently. 5-1, 4-0 and so on. These are statistics we can use.

Increasingly it appears we can’t pick and choose. Maybe we can’t beat Arsenal 5-1 and wish the keeper came out more. Maybe we can’t dismiss Everton at Anfield and then wonder why the manager doesn’t give people a rest more often. We’re learning, and unlearning. Losing some of the dogmatism we embraced during the Benitez era and getting to the core of what those six years were actually about: outcome not process, excitement not heatmaps, excellence not fundamentalism.

Rafa Benitez didn’t rotate his squad for its own sake, but to win football matches. Brendan Rodgers doesn’t pick unchanged sides for their own sake, but to win football matches. For Liverpool. He’s getting good at it. We’re getting good at it. Let’s all start picking our trees. Just in case, like.

I am one that didn’t really want Rodgers in the beginning. Not because he was terrible but because I had no idea who he was. He brought Swansea to a mid table finish in his maiden voyage? Great, but we’re Liverpool. My ego (THE LFC fans ego) was in the way. The results and change that he’s brought in his short time have been astronomical. I only realized the day after Fulham how close we still we’re to the title. I’m certainly a believer again, and I’ll be looking for some trees. COYR!! and thank you, Rodgers

I made two major predictions at the beginning of the season;-

1- that we’d be below mid-table by 1st January 2014;

2- that we’d be saying ‘Whatever happened to that Raheem kid?’

Nice article, which sums up my feelings of disappointment and disillusion post Rafa.

Rodgers is growing on me, I have to say – but as far as rotation goes, he doesn’t need to do it really, as we are not in Europe. Will be interesting to see how things pan out if we get back into CL.