“WE’RE not English we are Scouse!”

It’s the chant that irritates opposing fans more than any other. You can see the bewilderment; the disgust. You can almost see the thought process: “What makes you so different? What makes you special?”

Even within Liverpool, there are people who think that the sense of uniqueness, the separate identity, is an affectation. It is similar, they believe, to Manchester United supporters adopting the Argentinean flag after 1998 and the demonisation of David Beckham.

They are wrong. They do not understand where the notion of Scouse came from – or where it’s going. Sadly, the same is true of some of the most ardent proponents of the city’s individual identity.

What is Scouse? Almost everyone knows it began as a cheap stew, lobscouse – a word with Scandinavian origins. What most do not know is how recently it came to describe the inhabitants of the city. The word only crept into the vocabulary of north Liverpool after the First World War. It came into use in the dense slums between Scotland Road and the Mersey. It probably made transition from insult – Scouser being originally those who struggled to survive on the most meagre broth – to a tag of pride.

The Oxford English Dictionary claims the first usage of Scouse to be in 1945. They were 25 years behind the times. But one thing is certain. People described as Scousers – like the great James Larkin – would not have recognised themselves from the term.

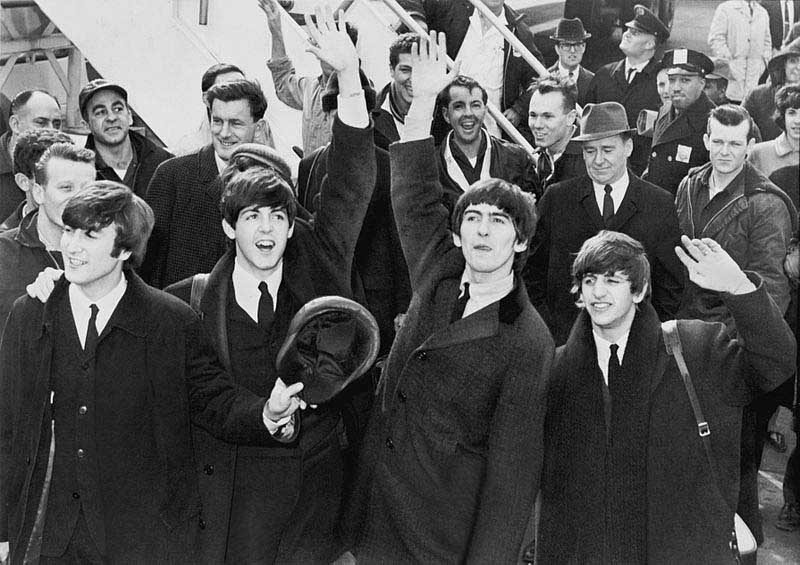

What would they have called themselves on the streets of Liverpool before the First World War? ‘Dicky Sam’ was one term, thought to mean ‘imitation Americans’. The sea trade with the United States meant that American fashions were always to the fore in the city – in the 1950s the ‘Cunard Yanks’ set the stage for the Beatles – but this phrase sounds more like an insult.

Wack, or Wacker still gets used, most often by those from outside the city, but there is a sneering ring to the word. How would the likes of Larkin have referred to themselves? Simply as Irish.

If Scouse, the dish, is a stew, so is the identity. The seaport brought together myriad cultures which helped shape this character. But its main ingredient is Irishness. The Liverpool we know was formed in the half decade after 1847, when the Potato Famine funnelled millions of starving immigrants into the port – “the nearest place that wasn’t Ireland.”

Many used it a jumping off point for the Americas or Australia, but enough remained to change the nature of the town. Particularly in the North End – bounded by Tithebarn Street, Great Homer Street, Boundary Street and the river – the city became a different country. The Scotland Road electoral district voted TP O’Connor, an Irish Nationalist MP to Parliament between 1885 and 1929.

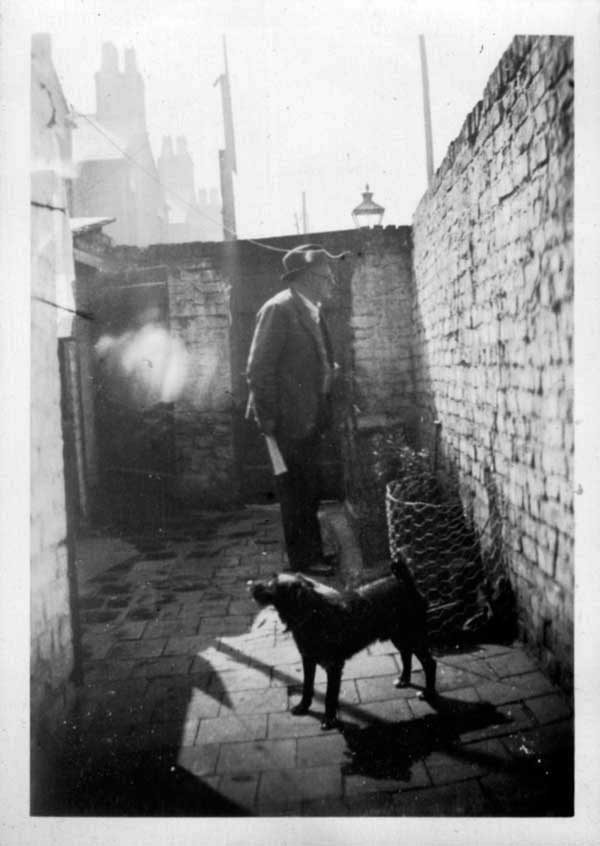

Liverpool back yard scene 1920’s // Flickr credit R.P.T.Owen

The relationship between Liverpool and the rest of the country was shaped and defined by this idea of an alien group of people within the body politic of England. This was the original enemy within. The people of Liverpool did not have to wait for Margaret Thatcher to be institutionally criminalised and regarded as outsiders.

Punch, with its cartoons of Irish as apes, captured the mood of post-Famine England with this satire from 1862:

“A creature manifestly between the Gorilla and the Negro is to be met with in some of the lowest districts of London and Liverpool by adventurous explorers.

“It comes from Ireland, whence it has contrived to migrate; it belongs in fact to a tribe of Irish savages: the lowest species of Irish Yahoo.

“When conversing with its kind it talks a sort of gibberish. It is, moreover, a climbing animal, and may sometimes be seen ascending a ladder laden with a hod of bricks.”

The ‘creatures’ in London were outnumbered and subsumed by the capital city and became part of its fabric.

In Liverpool, assimilation did not happen. It took much longer. When, four generations on, the Famine families found their links with Ireland stretched beyond where it was reasonable to consider themselves Irish, they became something else: Scouse. They still did not feel English.

Citizens of Liverpool often feel the media treat the city differently to other places. Outsiders attribute this to ‘self-pity syndrome’. In reality, it is rooted in the anti-Irishness that stretches back to the nineteenth century.

Crimes committed in Liverpool – like the Tithebarn Street outrage in 1874, where a man walking with his wife and brother was kicked to death while scores of people looked on – created a national sensation.

Incidents like this happened elsewhere but Liverpool was always portrayed as wilder, drunker and more violent.

Salford’s Scuttlers caused as much disruption as the High Ripper gangs of Scotland Road but the whiff of Celtic violence made it more sinister to the general public. It was easier to write off the violent confrontations that arose out of the crushing economic conditions as Hibernian wildness.

The transport strike of 1911, which brought Royal Navy gunboats on to the Mersey, was more palatable when dismissed as ‘Pat-riot-ism’ rather than recognising this was serious and potentially revolutionary social disorder on a grand scale.

Commentators still refer to Liverpool as ‘the capital of Ireland’. It effectively says: “They’re not English…” Yet the same pundits will sneer at the merest suggestion of Scouse particularism.

The notion of Scouse began to seep out of the Scotland Road enclave in the 30s and 40s and began to be embraced by those from outside the ‘Irish Slummy’ background. However, even in the Orange communities, where a picture of the Queen adorned every household, there was a knowledge that this culture was outside the mainstream of English life.

When Kenneth Oxford retired as chief constable of Merseyside Police in 1989, he said the most difficult part of the job was controlling ‘the Celtic fringe’. Scousers, from all ethnic and religious background, were still outside the pale of English society.

By the 1960s, the accent was distinctive and projected to the world by The Beatles. The south Lancashire tones of the pre-Famine seaport and the Irish of the post 1847-North End had fused into something quite different. This was the high water mark of Scouse culture.

The football teams, too, became flag bearers for identity. In Newcastle, Leeds and Birmingham, civic identity is overlaid by national pride. For many Scousers, the lack of connection to the state left a vacuum. This was filled by the football teams, Liverpool in particular.

For the rest of the world, the 1960s are the apotheosis of Scouse. Yet, the 80s saw it at its height. With a hostile government in power, the city showed its best qualities: resilience, unity, creativity and radical politics in the tradition of Larkin were all to the fore.

The forays to Wembley for the League and FA Cup finals gave Scousers a chance to display their identity and togetherness in the capital. There was a consciousness of heritage but the divisive components of the city’s history had receded to the point that they were almost inconsequential. The accent would never be more distinct.

Now? As the Thatcherite philosophers predicted, history is over. Few know or care about the genesis of their identity. The bonds with Ireland are long gone and the influence of the accent is fading from Liverpudlian tones. Lancashire is creeping back in around the edges.

Town is a shadow of its former self. The pubs and drinking dens of the city – even 20 years ago – felt unique. Now, the bars have a cosmopolitan, international feel. You could be in Tokyo, Los Angeles or Sydney. And the bright young things love it.

Liverpool One is hailed as a triumph. Yet it could be Newcastle One, Manchester One or Milton Keynes One. It chewed up the oldest dockside pub in the world, The Eagle.

During World Cups and European Championships, crosses of St George abound and as many people are horrified by booing the God Save the Queen as try to drown it out. A hard core will cling on to their Scouse separateness but more and more people from the city are marching in step with mainstream England.

Without a sense of tradition and a clear notion of distinctiveness, Scouse will become just like Geordie: a regional variation of Englishness.

That might be enough for some, but something special will be lost. Scouse is an accident of history. Its roots are not being nurtured enough. It will die soon and be replaced by something commonplace.

At least I’ll be dead, too…

• This article was first published in issue one of The Anfield Wrap’s free magazine. Editions 1-3 are available to download for Apple iDevices here: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/anfield-wrap/id583362683

• You can also view the magazine on any computer/tablet/mobile device here: http://app.theanfieldwrap.com

I absolutely love this article, I loved it the first time I read it and I enjoyed it just as much second time around.

Brilliant!

My father was born on Scotland rd.. 1922… his brother Billy Lowry was a Union / working class activist…. my father emigrated to the States but was always proud of his scouseness… I think scouse humor is certainly unique…I m disappointed that Paul Mc cartney took an English Empire title( sir paul!)… Lennon gave it back!

Awwwww the Eagle pub at least they saved the building as it was the first US consulate in the world, and the huge American Eagle outside it always looked great.

A rather depressing end to a super article. I have lived in the South West for a number of years now and feel more seperate and Scouse than ever. It’s not just the persistent attempts to laugh at my hubcap stealing tendencies or house breaking skills, it’s the values. There are a few Scousers around here and we see life so differently – we tend not to accept authority so easily. We will stand up more for what we think is right, we are louder and more bloody minded.

What saddens me is the gradual decline in ‘Scouseness’ when I get back for the odd games each season. Anfield used to be a refelection of ‘Scouseness’ with wools and others absorbed and given a lesson in how to behave as Liverpool supporters. Now it’s cosmopolitan and quiet – perhaps we as Scousers are a dying breed?

Tribe resents dilution by Untermenschen. Depressing stuff indeed.

You need to turn this into a book Tony. We need something that properly explains why we are the way we are rather than the usual “Learn to Speak Scouse” bullshit you can buy at the Albert Dock.

And then, when the book’s been written, they need to teach it in the schools!

If you’re looking for an excellent book on Scouse identity whilst waiting for Tony to write his, you might try Tony Crowley’s ‘Scouse: a social and cultural history’ Liverpool University Press (2012) – a history of the subject that debunks some of the myths around the origins and covers a lot of ground hinted at by Tony in this article which, I agree, is brilliant, but I also baulk a bit at the downbeat conclusion. For every Liverpool One there’s a Blackie, Bluecoat, Leaf, Fact, Motel, and – yes – TAW, that will keep the creative edge alive.

Excellent read. I’m not a scouser but as someone looking in – I’ve always been under the impression that the reason Liverpool doesn’t see itself as English but scouse was down to being the port and looking out to the world for it’s influences rather than inwards to England. It was good to read a more accurate explanation.

You mention that scouse was an accident of history, well damn right it is and I’m gutted about it. I’m from Chester and the Romans made us the port. It was only down to the River Dee silting that we ceased to be a port. It had to be moved up river to Parkgate on the Wirral but that silted too. Eventually, Liverpool became the main port and the rest is history and documented above. Just makes me think what could have been. Chester could have been in the Premiership now, with Liverpool in the Conference. It’s a cruel twist of fate that we could have given the world The Beatles but after losing the port, all we had to offer was Russ Abbott and Keith Harris of Orville fame.

The Irish have left their mark all over the world, a small Island with nothing but its people. We migrate, we work, we play, we build and destroy but we leave behind a uniqueness that will last forever. Liverpool, Glasgow, Boston and Sydney have become a part of our Nation and our sons & daughters will always keep the flag flying. YNWA.

Wow, what an article, loved it all.

Great idea about expanding article in to book.

Close similarities between Dubliners and Scousers, goes back to the cattle ships from Dublin to Liverpool in the 50s which also transported foot passengers of which my dad was one. Massive support for LFC in Ireland!

Globalisation, capitalism and the political establishment has eroded the working classes once trenchant beliefs and more importantly its will to fight to a position now where just getting to and from work is cause to be grateful. Dublin and Liverpool have given us Larkin and Connolly what chance of us getting anybody close to them again ? We had our chance in Dublin over the last 5yrs to fight back say NO and reclaim some part of our individuality our uniqueness our Irishness but unfortunately like the bottom half of the article we’ve decided to blend in with newcastle1 and liverpool1 to put it very mildly. That’s all history now problem is what happens when we’ve lost all of it ? Because the people taking it certainly don’t give a …..

I much prefer the term “We are Celts, not English!”. a testament to the fact that probably 2/3 of the people of the 4 Liverpool boroughs (Liverpool, Sefton, Wirral and Knowsley), are primarily of Irish, Welsh and Scottish descent.

by the way I support two teams. Liverpool and anyone who is playing England. I make no secret of the fact that I will be supporting Spain at this year’s World Cup and revelled at the recent mauling the England Cricket team took at the hands of big bad Mitchell Johnson and his mates! 5-0!

Loved the article and found myself nodding in agreement with much of it but I think you’ve misjudged the Geordies. Having lived in the NE for several years they certainly see themselves as being separate and apart from the English. The relative isolation of that part of the British Isles created a unique culture which owes more to their north sea neighbours than the rest of the country.

I am a proud Scouser,and a proud Englishmen…This anti English narrative has been pushed alot over the last 30 or so years,and its usually found to have an Irish agenda hidden somewhere within…Dont get me wrong,i am a huge admirer of the Irish and their influence on our city…Ive never been a huge fan of the South of England,but i have never let Southerners define my Englishness…I am lucky and proud to come from Englands best city.

Good article. You are a bit dismissive of the terms ‘wack’ and ‘wacker’. I’ve never thought of this as a pejorative and I believe it is a word for someone who shares stuff, especially food.

noun, 1. (Liverpool & Midland English, dialect), friend; pal: used chiefly as a term of address.

Word Origin: perhaps from dialect wack or whack to share out, hence one who shares, a friend.

Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

It should be noted that all the financial hardship suffered by Liverpool, (and indeed the rest of the country), was at a time when England was the wealthiest country on earth because of its empire.

Scouse not English is the way I have always felt. As a child of the 60’s and a man of the 80’s I never had anything to thank England for. Made to feel worthless by people who never cared for our city we stood firm and proud and showed what people we really are. Liverpool is built on its people and I am proud to be Scouse not English!

Always a good read – Tony’s sorely missed at The Times.

If I had to pick a few holes, I’d venture that his claim about the Irishness coming from Scotland Rd and environs completely misses the South End and the huge Irish enclave that correspondingly grew out of the Dingle (named after an Irish place) which was probably not much smaller in terms of Irish population and I think had more Irish churches – St Malachy’s, etc.

What a lazy, contrived heap of drivel. As usual overplaying the Irish and no mention of Scottish or Welsh. Anyone who thinks the Liverpool accent owes more to Ireland than Wales is living in a Hibernian fantasy land.

Is Lancashire really creeping in around the edges? I imagine that what is now the Liverpool accent is filtering out at least as much. That Liverpool accent has changed over the last generation of two as well. Much stronger and guttural now, mainly due to try hards who have been evident during the World Cup.

I have an inbuilt apathy towards the England side, in the same way I can’t get excited by watching Bury vs Stockport or Barcelona vs Milan. I don’t drape myself in a Croatian flag though.

Some of the this and the comments are quite strange one bragging about being a thief and burglar, no parent in the city or anywhere in the country would allow their child to be one, and would get battered if they took a sweet from a shop, anything else they would make them take it back, by the scruff of their neck if needed. Some silly romantacisum going on I feel. Maybe that’s to try to brush over the bad history. But as long as its learned from and never to be repeated, but sadly that’s not the case and society is failing everywhere.

Liverpool was always part of Lancashire also, only in the 1970’s did it become seperate. I’ve got a mix of Irish and Welsh, and Merseyside ancestry, but also Lancashire, which I’m so proud of them all as well as my Englishness. The respect and manners was passed down by my generations of ancestors, because even though we didn’t have much they cost nothing. So disrespecting anything or anyone isn’t at all anything like I would imagine any of my ancestors to have had for anybody anywhere on the planet never mind in England. As would have been the same with others. Some history is being brushed over for whatever reasons. (that’s not stating the obvious). Merseysiders have loads to be proud of as well as humour, music, football etc, so its not good to dwell on stuff, but to look forward and make sure its a place to always be proud of, where its safe for all children, and they are motivated to be whatever they want to be if they are willing to put the work in. Some are held back by parents not giving them the confidence they need, or also the schools, plus not a lot of support and guidance from them either. I know as I didn’t, (my parents and grandparents etc being factory workers or miners) but I had the will power to succeed in my choice of career. If only all had this, or most could? Because a place with no trouble but children are able to focus on what they want to do with their lives rather than get caught up in bad stuff and parents worrying about their safety. Maybe a dream, but does it have to be, and it would really be something to brag to the rest of the country about.