THE Stone Roses and the Euros made this a great summer for an older generation of footie fans who love music in equal measure but MARK DONAGHY remembers the “Third Summer of Love” of 1990, when football, fashion and pop beautifully collided to produce the subculture scene of the year

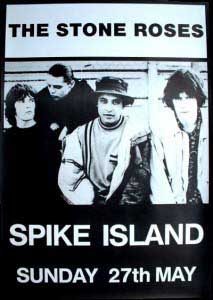

IT’S 9pm on Sunday, May 27, 1990.

I’m about five people and a security cordon away from Ian Brown, lead singer with The Stone Roses. Clouds of dust from the sun-dried soil are billowing up and filling my eyes and lungs. The surge from the thousands of fans is crushing my weedy teenage frame.

Brown sits down on the edge of the stage, crosses his legs like a primary school pupil in assembly and sings to me “I wanna be adored”, his eyes a mix of bewilderment and excitement.

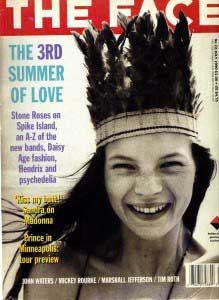

It’s the Stone Roses gig at Spike Island,Widnes; the opening ceremony of what The Face magazine in its July 1990 edition, featuring a 16-year-old Kate Moss’s debut cover shoot, would christen “The Third Summer of Love”.

Inside, the hipster bible dedicated 12 pages to the scene, explaining how the newest, most exciting youth explosion in Britain was being spearheaded by a heady mix of football, music and fashion.

“Mobilised by the acid/Balearic boom, set free by an uncaring government, football mad; all over the country, people are doing it in good style,” they said.

The summers of 1988 and 1989 are generally referred to as the “Second Summer of Love”, as the drug ecstasy fuelled dance floors and raves across the British Isles and Ibiza.

But for The Face, 1990 was when the scene started moving from the underground to the charts, via the terraces, with young “football thugs with flowers” making a new brand of funky, psychedelic rock you could dance to.

For a teenager brought up on the Beatles and loving the beautiful game, I couldn’t believe my luck.

At a time when you’re at your most impressionable, your brain at its most porous, soaking in as many influences as possible, I was swept along in the multi-coloured madness of it all.

The sounds, imagery and fashions may have been a mish-mash of pop’s past, but mixed with electronic beats, and a very working-class voice straight from the terraces, this was something which had never happened before. Something we could call our own.

The vocals were noticeably raw and working class, which, two decades ago, felt quite radical. Flowered Up’s It’s On is a classic example and the video, with the band and children sporting ultra-bright daisy head gear, is an aural and visual snapshot of that time.

Bands with the same ethos of football, great music and baggy clothes were being born across the country.

The NME and Melody Maker were busy raising the profiles of Paris Angels, The Farm, Happy Mondays, The Charlatans, The High, Northside and a reinvented, remixed Primal Scream.

For the first time since punk, there was a democracy about the music scene which invited anyone to have a go at making music. Band members looked like football fans and football fans looked like band members. Flares, Kickers and hooded tops were as likely to be seen on the terraces as they were on stage. Shops in Manchester’s Affleck’s Palace, the scene’s Carnaby Street, were heavily stocked with retro football kit inspired t-shirts.

The Boys Own fanzine neatly brought the themes of football, music and clubbing together, an attitude which was splashed all over St Etienne’s Only Love Can Break Your Heart, one of the songs of the summer, whose 12-inch featured a Mix in Two Halves, by Andrew Weatherall. The band would further cultivate their love of soccer and pop a year later with the release of their album Foxbase Alpha, which starts with radio commentary from a French football game and features a 1970s St Etienne player on its CD inlay booklet.

One band named themselves after the Portuguese legend Eusebio, while the Farm promoted the “No alla violenza” anti-hooligan t-shirts during Italia 90.

Of course, football had flirted with music and fashion before 1990, and has continued to do so since; teddy boys in the 1950s, mods in the 1960s and casuals in the 1980s were all fashion led subcultures which could be found on the terraces come 3pm on a Saturday.

But this cultural love-in was very different because of the ecstasy-fuelled environment it had been created in. This was more San Francisco 1967 than Brighton beach 1964. There was a noticeable smell of weed and reduction in violence on match days.

But this cultural love-in was very different because of the ecstasy-fuelled environment it had been created in. This was more San Francisco 1967 than Brighton beach 1964. There was a noticeable smell of weed and reduction in violence on match days.

Why did this scene happen in 1990? Just a year after Hillsborough, the beautiful game in the British Isles was in a dark place, which is probably one of the reasons Britain’s youth and pop culture, which has always been a home for outsiders and lost causes, took it under its wing.

It was a two-fingered salute to Thatcher’s Government, which was at war with both young people and football, introducing laws to stop acid house parties and taking every opportunity to chastise the game. In The Face’s Spike Island coverage, a fan can be seen on a photograph wearing a “Bollocks to the Poll Tax” t-shirt.

Looking back, this Third Summer of Love was year zero for both the rejuvenation of English football and the establishment of indie rock music as the mainstream sound of the nation.

That summer, England reached the semi-finals of the World Cup, Gazza cried and football was suddenly the wayward son welcomed back into the family home. Two years later and the Premiership was born. The rest is a tale of multi-millionaire mediocre footballers wearing earrings, a splattering of geniuses and wonderful moments, rising ticket prices and BSkyB paying £6m to screen one game.

The Stone Roses , meanwhile, were the trailblazers for the indie-guitar sound which dominated the charts for years, reappearing in the guise of Britpop and, later, in the early 2000s, as a slightly rougher bedsit version, led by the Libertines.

Youth culture, unsurprisingly, has turned its back on football since the early 1990s. The beautiful game is just not cool any more.

There’s no element of underground about it. It certainly isn’t an outsider and bands don’t borrow any of its codes or themes. The Premier League is as mainstream as Simon Cowell and X Factor and the last artist I can remember who used football’s iconography was Robbie Williams with Sing When You’re Winning. That says it all really.

One important link from the past to the present is the Justice Band, featuring musicians from the Farm, as well as Mick Jones and Pete Wylie, and fighting for the victims of Hillsborough.

Ian Brown and John Squire, as well as Eric Cantona, have joined them on stage and they supported the Stone Roses on their comeback gigs; a gentle reminder of a summer time long ago when football and pop were close allies and tried to change the world for the better.

Top 5 Third Summer of Love tracks

1. It’s On: Flowered Up – reached number 54 and was followed two years later by the epic Weekender.

2. Something’s Burning: The Stone Roses – b-side to single One Love. A trippier, summery track, more in tune with the times.

3. Together: Hardcore Uproar – released in August 1990, this song was created by two Hacienda regulars. Only intended as a white label, it reached number 12 in the charts

4. Only Love Can Break Your Heart: St Etienne – released in May 1990 and reached number 39. Brilliant electronic cover of the Neil Young song, recorded by Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs in a London bedroom.

5. World in Motion: New Order – “We ain’t no hooligans”, rapped John Barnes. Hooky tells a good tale of waiting outside Wembley for a cab following an England game in 1990, while Gazza went past in a stretch limo, containing women and champagne. “That should be me,” said the bassist, “I’m the rock star.”

Halycien days!!! Great to relive those days, great report. Remember trying to grow my hair and being gutted that it was curly. While all my mates were sporting a ‘shaun ryder’ I had a Ste McManaman.

The Stone Roses really weren’t terribly good. Sorry to have to point this out.